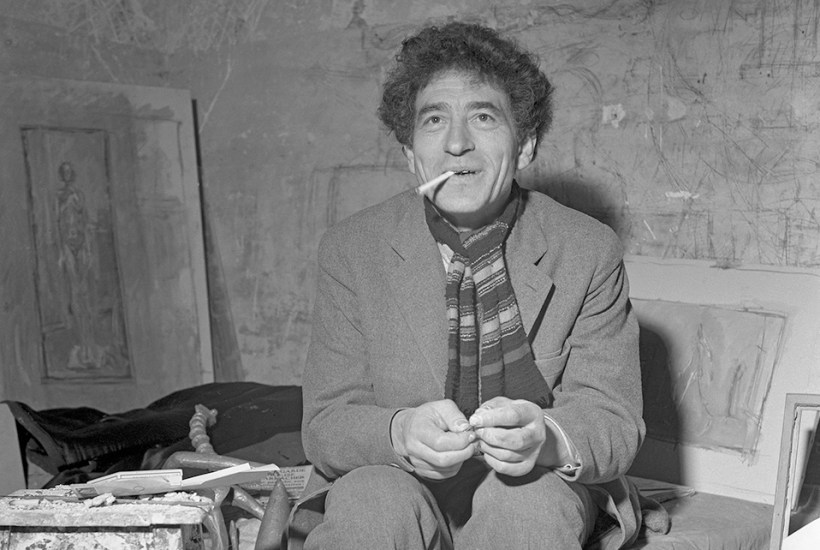

Michael Peppiatt is an octogenarian English art historian, based in London and Paris, who has met many of the artists he writes about. But, sadly, he never met Alberto Giacometti. He was working as a translator when, in 1966, he applied for a junior editor’s job at Réalités magazine in Paris and, much to his surprise, got it. He went to say goodbye to his friend Francis Bacon,who offered to give him an introduction to Giacometti. Bacon wrote it in felt-tip on a torn-out page of Paris Match and told Peppiatt to take it round to Giacometti’s studio, which he did. But then he stood irresolute at the door, lacking the courage to knock.

He went again the next day, and the next, ‘but the same paralysing shyness and shame at trying to impose myself on a world-renowned artist overcame me’, and each time he slunk away. And then his colleagues at Réalités laughed and said didn’t he know that Giacometti was dead? He died a few days ago. Peppiatt could have knocked at the studio door as much as he liked but Giacometti would never have answered.

For Peppiatt, this was the start of a lifetime obsession. He collected all the printed material he could find on Giacometti: old catalogues and articles, and especially photographs of his studio – the studio he had just missed entering. It was a terrible hovel in rue Hippolyte-Maindron, with no heating or running water, a roof that leaked and a beaten-earth floor. He also gradually got to know people who had known Giacometti: his brother Diego, his widow Annette, his New York dealer Pierre Matisse (son of Henri), his Paris dealer Aimé Maeght, painters such as Balthus and André Masson, and photographers such as Brassaï and Henri Cartier-Bresson, who had often photographed Giacometti in his studio. And, after seeing a Giacometti retrospective at the Orangerie, Peppiatt says: ‘My attachment to Giacometti grew into the bedrock of my existence.’

So he has written this biography, starting with Giacometti’s move to Paris in 1922 when he was 20. Giacometti came from an obscure village in the Val Bregaglia, high up on the Swiss-Italian border, and had already studied in Geneva and Rome and was recognised as a precocious talent. His father, Giovanni, a successful regional painter, urged him to study art in Paris and enrol in the art school at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, which he did, but not for long. He preferred to rent his own studio, however squalid, and just get on with his work. And his younger brother Diego came to join him, taking care of all practical matters.

At first, Giacometti was lonely in Paris but soon the surrealists took him up and he was hailed as ‘the sculpture-wunderkind all Paris is talking about’. Salvador Dali and Jean Cocteau praised him and Man Ray photographed him in his studio. He acquired a dealer, Pierre Loeb, who paid him a salary of 1,500 francs a month, and the Vicomte and Vicomtesse de Noailles bought his work and invited him to dinner at their palace, where liveried footmen stood behind each chair.

But although Giacometti wrote for surrealist magazines and contributed to surrealist exhibitions, he was never completely committed, and in 1934 he rejected them entirely and said that all the work he had done in a surrealist vein was ‘masturbation’. André Breton, who had been almost a father figure, cut him off and many of his old friends dumped him, even crossing the street to avoid him. For a while he felt very isolated. But he soon made new friends – André Derain, who encouraged him to start painting again, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and Samuel Beckett.

Giacometti worked all day and at night walked the streets of Paris in search of prostitutes. ‘I was obsessed by prostitutes,’ he wrote. ‘Other women simply didn’t exist… I wanted to see them all, know them all, and night after night I set off on my long lonely trails.’ Often he just watched them, but sometimes he hired them too. He preferred sex with prostitutes because he wouldn’t have to apologise if his potency failed, which it often did, and he also appreciated their skill. He was wary of relationships with ‘nice’ girls, and did not finally marry one, Annette Arm from Geneva, until 1949. He took her home to meet his mother, who approved, and he painted their portraits in identical poses, as though they occupied the same position in his psyche. He knew there was no risk of Annette producing children because he had suffered mumps in adolescence.

During the Nazi occupation, he went to Switzerland to visit his mother and did not return to Paris for four years. Before he left, he and Diego dug up the studio floor and buried his sculptures in the earth. When he returned, they were still safely there. But his Swiss exile had an odd effect on his work: his sculptures got smaller and smaller and ‘stubbornly shrank to one centimetre high’. He was able to carry all the work he had done in Switzerland in a small box: ‘Four years of trial and error, years of relentless creation and destruction.’

It was only on his return to Paris that he could make taller figures again, though they were always skeletally thin. In l948 he was given his first retrospective in New York and MoMA bought three of his works. By the early 1950s, collectors were queuing up to buy his art and paying him in wads of cash, or even gold bars, which he stashed in shoe boxes under the bed. But he still insisted on living in the squalid rue Hippolyte-Maindron studio and flatly refused Annette’s dream of having modern heating or an indoor bathroom. He gave money to his mother, to bar girls and beggars, but never to his wife.

In 1962 he was awarded the Grand Prix for sculpture at the Venice Biennale, and also given a huge retrospective at the Zurich Kunst-haus. He was rich and lauded, but also ailing. He had a bronchitic cough from years of persistent smoking and a constant searing pain in his stomach which eventually drove him to the doctor. He was found to have a large, malignant tumour that necessitated the removal of four-fifths of his stomach. He found the whole experience strangely exhilarating: ‘To live two months knowing that one was about to die, that would be worth 20 years of unawareness.’ And it gave him a new lease of life and a wanderlust that he had never felt before. He went to London, New York and Copenhagen, and then back to Paris to resume his punishing work routine. Annette still sat for him during the afternoons, but his new mistress, Caroline – ‘his ultimate, dominating, dangerous muse’ – took over at night and ‘when he painted Caroline he was painting his own madness’.

The Tate Gallery gave him a full retrospective in 1965, and the curator, David Sylvester, walked him through it. He looked at it all silently and then pronounced: ‘Well, it’s all shit, but it’s the best shit there is.’ When his old friend Brassaï came to photograph him later, he found ‘an emaciated, bent Alberto Giacometti, tottering around in his old clothes, his face lined more than ever by suffering’. Giacometti told him: ‘Photograph me like this. I’m a wreck. The future looks dark. I ask myself for how long I can keep on working.’

The answer was not long. At New Year 1966 he was admitted to a Swiss hospital with chronic bronchitis and exhaustion, fell into a coma and died. He was 64. By then he was hugely admired all round the world, but he never knew the pleasure of self-satisfaction. He believed in his friend Beckett’s mantra: ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better’, and wrote: ‘Failure is my best friend. If I succeeded, it would be like dying. Maybe worse.’

This book is not only a wonderful portrait of Giacometti, but also of many of his friends and associates. Peppiatt is at home in the whole Paris cultural scene and hops merrily from La Coupole to Les Deux Magots to Café Flore, picking up fascinating details along the way. Did we know that Sartre ate nothing but sausages and could do a perfect impression of Donald Duck? We do now.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in