Writing for the Brownstone Institute, Debbie Lerman asked a provocative question: ‘What If There Had Been No Covid Coup’ and the leading US public health agencies had been left in charge of the pandemic response? Instead, it was taken over by the National Security Council and the departments of defense and homeland security. The prevailing assumption being, of course, that the same set of responses would have unfolded over the next two to three years. She refutes this and explains with great clarity and considerable plausibility why the national security elite had to take over and what the implications are.

For one thing, the existing national and World Health Organisation guidelines would have been followed, to wit: don’t panic, treat serious cases on presentation, keep society functioning as close to normality as possible, and look for inexpensive and widely available early treatment options to reduce the risk of serious illness. With national security agencies taking over, the new pandemic response paradigm became that of biowarfare: shut down society, institute medical countermeasures, and develop and roll out vaccines at warp speed. Designed to counter biowarfare and bioterrorism, they upended the scientific underpinnings and ethical principles of existing public health-based interventions. Propaganda, censorship and silencing of critical and dissenting voices were essential and therefore integral to the new normal.

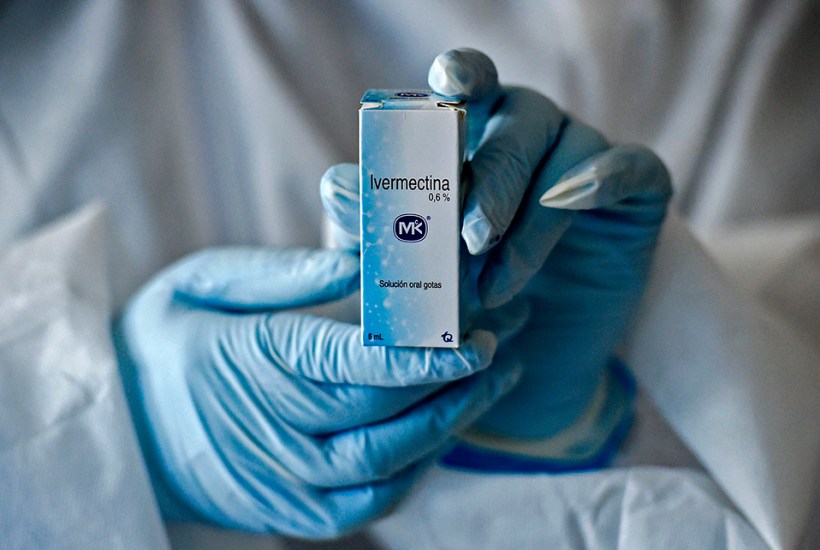

In a complementary article, also for Brownstone, Dr Meryl Nass speculates that ‘maybe the vaccines were not made for the pandemic, and instead the pandemic was made to roll out the vaccines’. As part of the evidence, she notes that Australia, the EU and the US were purchasing 8 to 10 vaccine doses per capita in mid-2021, despite unresolved doubts over their safety and prophylactic efficacy in infection and transmission. Because these were unresolved, the Covid vaccines could only be granted ‘emergency use authorisation’ after a public health emergency had been declared in order, says the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to ‘prevent serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions when certain statutory criteria have been met, including that there are no adequate, approved, and available alternatives’. In sum, fear porn was necessary to convince the public of the gravity and urgency of a public health emergency, which was then used to justify cutting corners in the development, manufacture and rollout of vaccines. But this could not be done if an alternative treatment was available. It therefore became necessary to reject any role for cheap, widely available and potentially lifesaving drugs like hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, repurposed to treat Covid-19, and doctors were banned from recommending them for prophylaxis and early outpatient treatment.

With around four billion pills sold around the world over several decades, ivermectin’s safety profile was well established. There were three parallel tracks along which to assess ivermectin efficacy and risks: randomised control trials, observational data and meta-analysis. The signals from all three indicated moderately positive outcomes. These included observational data from Brazil and states in Peru and India, plus meta-analyses supported by the WHO, Stockholm-based physician Sebastian Rushworth, and biostatistician Andrew Bryant and medical doctor and researcher Tess Lawrie. These showed between 56 per cent and 62 per cent mortality reduction associated with ivermectin use. However, although suggestive, these were not conclusive enough to establish ivermectin’s efficacy in preventing and treating Covid.

A study of ivermectin (IVM) use in Peru, using excess deaths rather than deaths with Covid as the yardstick, found a 74 per cent mortality reduction in the 30 days after peak deaths in the ten of Peru’s 25 states with the most intensive IVM use. Strikingly: ‘During four months of IVM use in 2020, before a new president of Peru restricted its use, there was a 14-fold reduction in nationwide excess deaths and then a 13-fold increase in the two months following the restriction of IVM use’.

Unfortunately, pharmaceutical companies frown on cheap generic drugs like ivermectin and few regulators of rich Western countries were able to escape industry capture. On 4 February 2021, Merck – which makes patent-free low profit Ivermectin and has been selling it for years – questioned its safety. In August 2021, the FDA warned Americans against taking ivermectin, a medicine used to deworm livestock: ‘You are not a horse. You are not a cow. Seriously, y’all. Stop it’. The next month, Australia’s TGA banned GPs from prescribing ivermectin for preventing or treating Covid-19, citing ‘a number of significant public health risks associated with taking ivermectin in an attempt to prevent Covid-19 infection rather than getting vaccinated’. In other words the ivermectin ban was meant to promote vaccination.

The August 2021 tweet from the FDA, reinforcing the message that ivermectin was a horse de-wormer and not authorised to treat Covid-19, went viral. In response, some ivermectin-prescribing doctors took the FDA to court. During oral arguments in a US appeals court on 8 August 2023, Ashley Cheung Honold, a Department of Justice lawyer representing the FDA, said the ‘FDA explicitly recognises that doctors do have the authority to prescribe ivermectin to treat Covid’. Australia’s TGA had already lifted its restrictions on IVM from 1 June 2023. Suspicions grew that the financial interests of the pharmaceutical sector might have unduly influenced regulators’ decisions in banning the use of ivermectin. These have been strengthened with the removal of the bans: how can a product that was considered safe for decades before 2020 but banned during 2020-22 suddenly become safe once again?

In this connection, it is worth noting that the Peru study was published in preprint on 8 March 2021, yet it was not published as a peer-reviewed article in the Cureus Journal of Medical Science until 8 August 2023. The journal says its average time from submission to publication is 33 days. Readers can draw their own conclusions.

On 12 May, Governor Ron DeSantis signed four laws aiming to give Florida the strongest protection of medical freedoms in America. The package protects citizens against testing, mask and vaccine mandates by government, business and educational institutions. It also protects medical professionals’ freedom of speech and their right to prescribe alternative treatments to their patients.

Writing in the Federalist on 21 August, Jay Bhattacharya and Martin Kulldorff, two of the three authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, argue that after the litany of lies, abuses of power and conflicts of interests exposed during the Covid years, the US Congress must enact structural reforms of the National Institutes of Health.

Could we please copy both initiatives?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in