Recently I stumbled across a file of conversations I’d recorded with my seven-year-old son Frank back when he was four. Topics include his travels through wormholes, why he finds planet Earth ‘boring’, the tragic story of how his ‘first family’ died and how he got his ‘laser eyes’.

It was only by listening to these voice notes three years later that I understood just how precious audio recordings are, and also how under-used. The conversations I taped illustrate the nuances of Frank’s four-year-old self more vividly than any photo or video could. Anyone attempting to write fiction should take note of the power of audio – conversation and voice are how character is built. A physical description tells you relatively little. Why don’t we record more conversations, I wonder, if only for posterity’s sake?

Preserving everyday verbal interactions between our loved ones is something we don’t do enough of, in my view. In an era when everything else is itemised, filed and archived, the possibilities of audio seem strangely overlooked. Part of it is the unobtrusiveness of the medium. There is a covert slyness to audio. Most people instinctively object to the idea of being recorded, and yet we allow ourselves to be videotaped pretty much constantly: almost everywhere in this country we’re captured on CCTV without our knowledge or consent. We take photos and videos of our children and loved ones throughout the day and then post them online for any number of people to see. Yet the thought of recording the things people actually say in situ, no matter how sweet and innocuous, seems suspicious at best – and galling at worst.

Perhaps it’s simply a problem with association. Taping people feels like espionage, as if we’re collecting the material for later blackmail. It tends to be done in moments where someone is trying to catch another out. In many countries (including England) for precisely this reason it’s illegal to make public a recording taken without consent. But audio recordings for personal use are allowed, and recordings of real, everyday conversations are like nothing else when they’re made with attention and love.

It might seem as if video combines the best of both worlds, but the moving image has nothing on a simple audio recording. Voices and body language change on camera; the subjects become overly conscious of themselves.

Listening to that old conversation with my son Frank, I so badly wish I’d made hundreds. In fact I would love nothing more than to listen to an archive of all my lost conversations with loved ones – it’s this that we miss most when people are gone. To be able to hear and replay the words they once said to us – in their actual voices – is comforting and exciting. It’s like digging up buried treasure from the past.

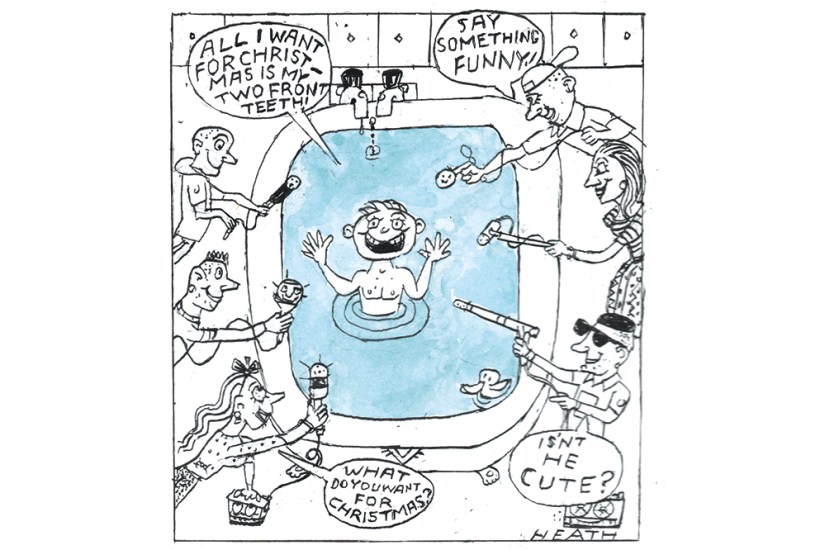

I remember why I taped those early conversations with Frank. I was doing a lot of telephone interviews for print magazine stories at the time and I’d noticed how much more present I was – as a listener, interrogator and person – when I knew I was being recorded. Frank loved talking in the bath (he still does). This was the place where his little mind fully opened up. He was at that magical point in childhood where he had just acquired a full grasp of language but had not yet learned to distinguish between fantasy and reality. I wanted to bottle him in a jar half the time; the other half I was so exhausted I wanted to cry.

I noticed that if I was able to give Frank my full, undivided attention he would tell me the most astonishing things, but because bath time occurs at the end of the day I would often feel myself becoming impatient. I realised I was missing things, hurrying him into the future. He could sense this, of course, and it irritated him. On the worst nights, what could have been a tender discursive chat devolved into pre-bedtime bickering, which never speeds anything up.

Aware of what I was missing, and that I would come later to regret it, I tried making bath-time videos. But Frank’s awareness of the camera changed the way he behaved. He’d either become self-consciously cute and performative or crabby – the videos just didn’t work. The voice notes were a discovery. They did not alter Frank’s behaviour, but hitting record did force me to slow down and be a better listener. With the tape rolling I became more aware of myself, in a way that helped me to be present. The result was that Frank opened up and gave me a full tour of his amazing four-year-old brain – a lost landscape I will never get to visit again but, through the magic of audio, was miraculously able to preserve.

After finding the ‘Frank bath file’, I’ve resolved to try to record more everyday family conversations just for posterity – a resolution of sorts. Here’s hoping the boys don’t sue me later.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in