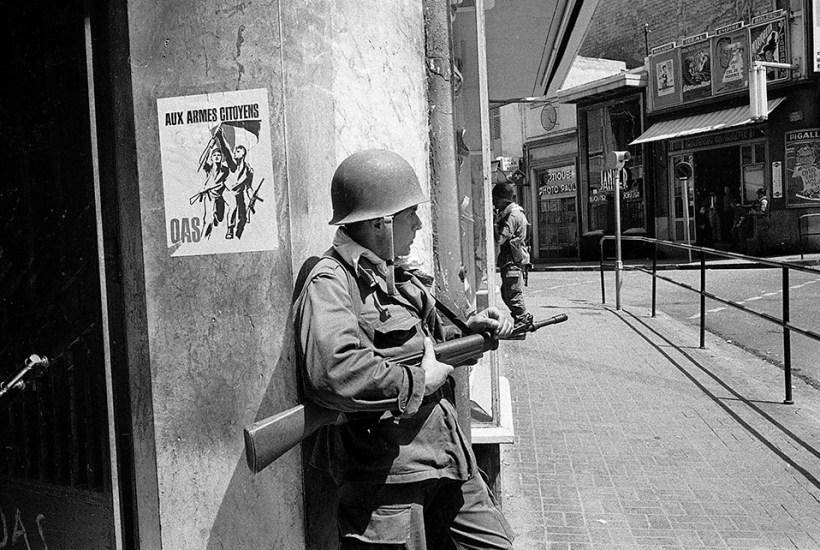

The ‘chase’ thriller is the fallback choice of writers looking for an easy way to make the pages turn. The Continental Affair (Bedford Square, £16.99) shows a gifted writer embracing the more obvious traits of these novels, while adding some innovative twists of her own. The story is set during the Algerian war that led to independence; its co-protagonist Henri is a former Algerian gendarme, of French and Spanish descent, who deserts when he is made to interrogate a childhood friend. Henri takes refuge in Grenada among his late mother’s family – countless cousins, and all of them crooks. As they get to know Henri, the cousins decide to give him a task which is also a test: he’s sent to collect a package left by a woman in a courtyard. But another, mysterious, woman beats him to it, and leaves with what Henri can see are bundles of banknotes.

Louise, the unknown woman, is English, recently released from a life spent looking after her invalid father; her mother scarpered years before. When the father finally dies, Louise takes the £40 she finds in the house and goes to Spain. There, as her money is about to run out, she witnesses the drop. Grabbing the cash, she heads for Paris, where her mother was last heard from many years ago. Following her, Henri vows to recover the money, but each time the opportunity arises he finds an excuse not to act, to the growing consternation and eventual fury of his cousins.

The novel is told in what is at first a slightly confusing alternating time-frame, but as we start to make sense of it the story becomes engrossing. There are occasional historical references – such as the 1961 Paris massacre of Algerians by the French National Police – but not enough to distract from the book’s spotlight on the unlikely travelling pair. Both are wounded souls; both also sense this in the other, enough to unburden themselves. Though Christine Mangan’s story ends with a classic sort of confrontation, what persists for the reader is the troubled duo at the book’s deeply imagined heart.

The bird of Louise Doughty’s A Bird in Winter (Faber, £16.99) is a family nickname for Heather, an officer in the secret service, who after 20 years in its employ inexplicably gets up in the middle of a staff meeting, leaves the room and doesn’t come back. Thereafter, she’s on the run – though from whom and why is only gradually made clear, since interspersed with her flight is a jerky but compelling account of her earlier life.

Before intelligence work, Heather was in the army, where she formed a close friendship (subsequently ruptured) with another soldier, named Flavia. Heather otherwise keeps her distance from everyone. She is a tough but emotionally dislocated woman who sleeps only with older men, does not want children and excels at the duller parts of her work – strategy and liaison – that no one else is good at.

It is not an actionless book – when at one point Heather is found, there follows a scene of truly gruesome violence – but its strengths lie in the rich if piecemeal portrait of Heather that gradually emerges. As the book moves towards its unusual climax, Doughty reverts to more conventional thriller mode – like an angler who, happy to let a hooked fish run, suddenly remembers the purpose of the exercise and quickly reels it in. We discover who has betrayed whom, enjoy a well conceived twist and get all the answers to the questions we ask when Heather first goes on the run. It is not badly done at all, but seems slightly disappointing after the unusual narrative that precedes it, as well as the deceptively casual prose, which is masterfully attuned to the laconic, even depressed mindset of its heroine.

After two excellent spy thrillers set in foreign terrain (Syria and Istanbul respectively), James Wolff stays in the UK for The Man in the Corduroy Suit (Bitter Lemon Press, £9.99). When Willa Karlsson, a veteran member of the intelligence service, is hospitalised and poisoning is suspected, Leonard Flood is called in to investigate. Flood is a gatekeeper, one of the officers whose job it is to unearth the enemy within – double agents working for the other side. Flood is also a maverick, regarded warily by his colleagues, seen as a sometimes uncontrollable force whose conduct of interviews is legendary for the unbridled aggression he brings to them, the relentlessness of his questioning and his heartless ‘ability to kneel on the bruise’.

With the help of Fanny, an equally clever but more decorous colleague, Flood makes rapid progress with the case, his investigations moving from a revealing exploration of Willa Karlsson’s flat to a country hotel in Norfolk where she often stayed. But just as we think everything is about to be wrapped up, a magnificent reversal occurs, instigated by Flood himself. After this, the author leaves the binary question of spy or not, and instead focuses his story on what Flood should do about the answer.

Wolff’s prose mixes vivid similes and subtle suggestion: a gardener has ‘a face like an overcrowded tray held by someone unsure of their footing’; and, of Flood himself: ‘He idolised his father, who left when he was ten and didn’t come back. For a few years after that, Leonard was convinced he could speak to animals.’ The writing is extraordinarily good throughout, something which has distinguished Wolff since his debut.

In Bad Men (Zaffre, £14.99) by Julie Mae Cohen, the only chase is a romantic pursuit. Saffy Huntley-Oliver is an American living in London who sets her cap at Jon Desrosiers, the creator of a popular true crime podcast. Abandoned by his wife, Desrosiers goes to Scotland to lick his wounds, and Saffy surreptitiously follows. She engineers a meeting by endangering a dog whom Desrosiers rescues, then contrives to meet him on the train back south, and encounters him yet again, supposedly by chance, on a London street. By this point one begins to wonder if Jon, for all his broadcasting savvy, is simply dim; certainly his obtuseness suggests Saffy’s own vocation is not about to be exposed. For in a secret life she is a serial killer, whose expertise with corpses proves useful when a severed head is left by Jon’s front door and the two investigate how it got there.

As love stories go, this is perhaps more conventional than it seems, since shared danger is such a traditional catalyst for love. And Saffy the heroine is a lesser version of the female serial killer in Chelsea G Summer’s A Certain Hunger, in which we accepted the heroine’s murderous capers because she was obviously completely mad. In Bad Men Saffy doesn’t seem crazy at all, which makes her murders, especially one late in the book, gratuitous as well as distasteful. Comedy and thrillers are crime fiction’s sugar and salt – potentially consumable together, but not readily compatible. A preponderantly comic mode is hard to sustain in a story intended to thrill (which makes Mick Herron’s accomplished mixtures even more remarkable), and although Cohen has written an admirably ambitious knockabout story, her crime debut ends up showing how difficult this is to do.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in