Sicily is far removed from the gracious suavities of Tuscany. With the souk-like atmosphere of its markets and obscure exuberance of life in the old Cosa Nostra towns, the Mediterranean island is halfway to Muslim Tunisia. The British Tuscanites who descend on the hills around Florence during the summer holidays as part of their ‘Toujours Tuscany’ dream – Tony Blair, Sting, David Cameron – are thankfully nowhere in evidence.

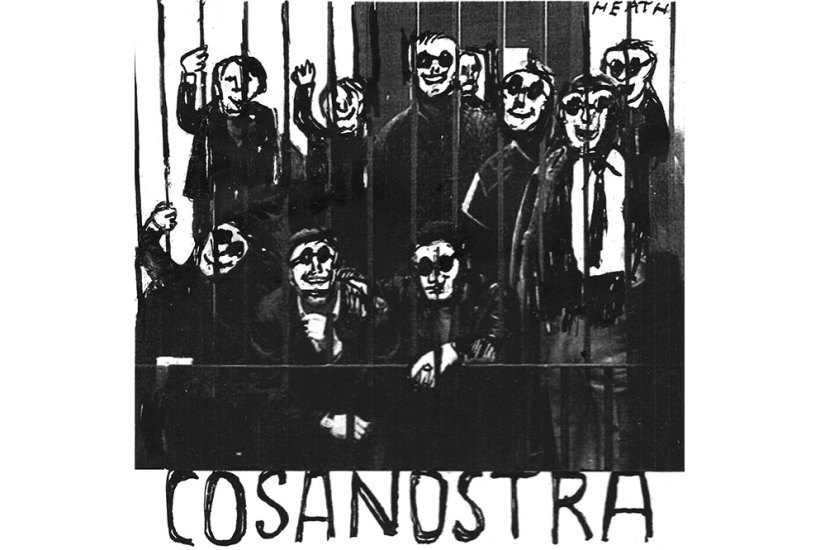

In our post-Godfather world no history of Sicily would be complete without mention of the Mafia. The word is said to derive from the Arabic mahyas, meaning ‘aggressive boasting’: for almost three centuries until the Norman Conquest of 1061, Sicily was an Islamic emirate. I had come to a small town in the Mafia-dominated west of the island to talk about the Sicilian detective novelist and essayist Leonardo Sciascia (pronounced sha-sha), whose work I translated. Sciascia was born in Racalmuto in 1921; for years, the Mafia spread its tentacles into the town’s sulphur industry, but the sulphur mines are closed now, and add to a derelict air. Sciascia’s father, employed in the Racalmuto mines as a bookkeeper, was the son of a caruso, or child miner. Unsurprisingly, sulphur’s jaundice-yellow is emblematic in Sciascia’s fiction of Mafia-related extortion and cruelty. In his first Cosa Nostra-themed novel, The Day of the Owl, published in 1961, the face of a bus conductor caught up in a shotgun vendetta is ‘the colour of sulphur’. In Sicily’s age-old burden of injustice and death Sciascia found a drama that served him well as a writer who cast an inquisitorial eye on political corruption in all its guises. He died in the Sicilian capital of Palermo in 1989, at the age of 68, a lifelong heavy smoker.

In Racalmuto my wife and I were put up in a hotel whose rooms were named after characters in Sciascia’s books. (Ours was ‘Captain Bellodi’ – the hapless carabinieri officer in The Day of the Owl.) In the salt stickiness and African heat of midday we were ready to collapse. I was 24 years old when I interviewed Sciascia in 1985 for the London Magazine. With juvenile impertinence, I telephoned him without an introduction from a bar on the Palermo outskirts and demanded an audience. I recall that I wore a dark blue tie and dark blue jacket for the interview, as Sciascia himself dressed in what I took to be Sicilian formality. Three decades on, Sciascia’s grandson Vito Catalano decided to publish the interview as a book, Una conversazione a Palermo con Leonardo Sciascia. At the book launch that evening in the courtyard of Racalmuto’s 18th-century town hall, I was asked if Sciascia was much read in the English-speaking world. I had to say that he is not, though Caroline Moorehead is currently writing a book about him, and Gore Vidal was always an admirer.

Next day we visited the Greek temples in Agrigento province, of which Racalmuto is part. The heat was ferocious and I was glad to be able to make a sun hat out of the copy of the Times Literary Supplement I had in my bag. (Samuel Beckett usefully described the TLS as being ‘impermeable to farts’). The last time I visited the Valley of the Temples was with my sister Clare, who died too early, last July, at 58. I am left with a sense of lost chances, terrible grief and unfinished business. Sicilians are a death-haunted people who understand dying in the way many northern Europeans with their noses to the grindstone find hard to understand.

Palermo’s turban-wearing Saracen ancestors would have been astonished by the noisy beep and brake of traffic in the city today. After interviewing Sciascia that winter day 38 years ago, I was mugged by a couple of hoodlums on a souped-up Vespa; I ran after them shouting ‘mascarponi!’, a homonymous near-miss for ‘mascalzoni’, Italian for ‘rascals’, which is what I had intended. The expression on the policeman’s face when I explained that two ‘cream cheeses’ had made off with my shoulder bag was one of pity. The bag contained a paperback edition of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot and a roll of lavatory paper.

On the way back from Racalmuto to the villa where we were staying in the hills beyond Cefalù, we saw evidence of the wildfire damage wrought by anticyclone Nero: burned fields, burned olive groves. Mount Etna on Sicily’s Catanian coast had erupted and Catania airport (where temperatures had reached a purgatorial 47˚C) was closed as a consequence. Our villa, designed by the Palermitan architect Adriana Bisconti, was situated below Pollina in the cool green uplands of the Madonie national park. Out to sea loomed the volcanic archipelago of the Aeolian Islands, where my friend Gaia Servadio (one of Boris Johnson’s disappointed mothers-in-law) used to keep a home. Otto, our villa cat, drank from the swimming pool in the mornings while giant black Sicilian bees fed off purple carob blossom.

On my wife’s birthday, 15 August – the Feast Day of the Assumption of Our Lady – we ate in a wayside inn in San Mauro Castelverde that served Madonite specialities of pan-fried prickly pear skins (without the spines), snails in tomato sauce and wild boar salami. For pudding came crispy fiorello (little flower) confections filled with ricotta and sugary pistachio paste. It was the Arabs who first bit a sweet tooth into Sicily: ‘Leave the gun. Take the cannoli’, as that line in The Godfather goes.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in