In the months before Russia invaded Ukraine last year, Volodymyr Zelensky was fighting for his political life. The former comedian was elected in 2019 on a pledge to end the war in Donbas by an electorate exasperated with its political class. Zelensky initially set out to negotiate with Vladimir Putin – but achieved nothing. He appeared naive and out of his depth.

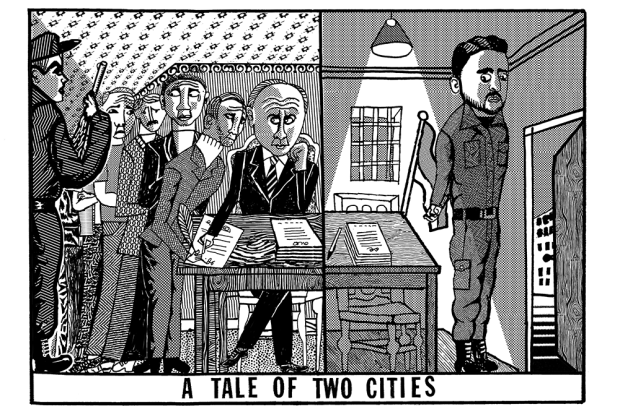

However, Zelensky’s transformation into a wartime leader captured the world’s imagination and rallied his allies. Yet some of those allies are beginning to ask whether, if this war is really about the free world versus autocracy, as Zelensky claims, Ukraine should hold a general election next year.

The Republican senator and staunch Ukraine supporter Lindsey Graham recently told Zelensky during a meeting that he wants to ‘see this country [Ukraine] have a free and fair election even while it is under assault’. Zelensky said that if the £110 million election cost is covered, he could make it happen.

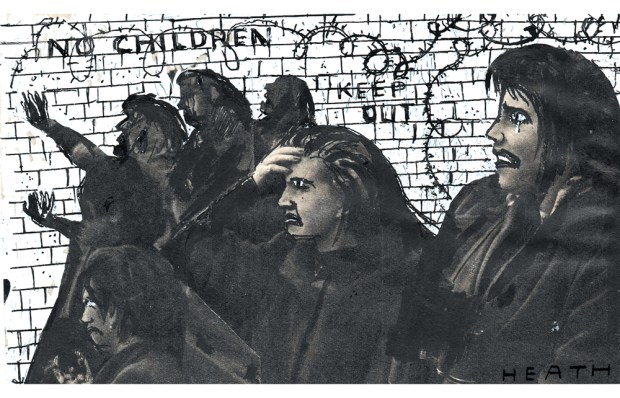

Ukrainians, however, are generally wary of foreign demands for an election. To many, it appears as if the West wants to swap Zelensky for a leader who would be more likely to compromise with Moscow. But the chances of such a leader being elected are negligible. I spent the summer in Ukraine talking to politicians, soldiers, aid workers and ordinary citizens. All of them detest this war, yet not once did I hear anyone put the case for making concessions to Russia. Opinion polls confirm this. Any president who tries to sell out will be thrown out, as the 2014 Maidan revolution demonstrated.

An election would make very little difference. Zelensky has an unprecedented trust rating of 80 per cent. An even higher proportion say that fighting should continue until Russia leaves the country entirely, including Crimea. This might sound like a hardline position, but in Ukraine it is an accepted and deeply held standpoint. Polls show that only a quarter of Ukrainians wish to replace Zelensky even if they were to win the war.

An election would also serve to illustrate that, as a consequence of the war, there is no serious opposition to Zelensky. Television has long played a vital role in Ukraine’s political debate. The channels are usually oligarch-owned and promote certain politicians. A large TV channel has the power to propel an unknown figure into pole position in a state election; equally, it can attack the enemies of whoever owns the station. But the old variety of TV news has been replaced by exclusively pro-government programmes, with all commercial television now under state control. Three channels run by Petro Poroshenko, the fifth Ukrainian president and the second-most popular politician until the 2022 invasion, have been turned off. Pro-Russian parties have been proscribed, but Poroshenko has pro-western views and is unlikely to pose a threat to national security. Banning his channels looks more like an attempt by Zelensky to silence an opponent. This was a tactic of his even before the full-scale war: to consolidate power and eliminate potential competitors.

Ukraine’s six big TV news channels have been merged into one ‘United News’. Initially, it kept Ukrainians informed about the latest developments in the war. Over time, it has transformed into a promotional platform for certain members of Zelensky’s party, specifically Mykhailo Podolyak, one of his chief advisers, and Andriy Yermak, head of the President’s office. There’s precious little airtime for the Ukrainian opposition. ‘European Solidarity’, Poroshenko’s party, is the only opposition force with the potential to make any impact in the next parliament.

Vitali Klitschko, a former world heavy-weight boxing champion, was another favourite before the invasion. He was elected mayor of Kyiv and the head of the Kyiv City State Administration almost a decade ago and rebelled when Zelensky tried to take control of his office – creating an enmity which is now on full display. Each man seeks to exploit the other’s failures. When Zelensky was asked who was to blame for the scandal about the unusable bomb shelters in Kyiv, he replied that ‘there could be a knockout’, a clear reference to the boxer. This scandal hit Klitschko’s popularity, but did not administer a decisive blow. He is one of the few people who could pose an actual electoral threat to Zelensky, despite several corruption scandals and involvement in illegal construction in the capital.

Yulia Tymoshenko, the country’s former prime minister, who co-led the Orange Revolution, has had three failed runs for the presidency but may try again. She’s a divisive figure, however, as a result of having struck oil deals with Russia in the past. Dmytro Razumkov, a former chairman of Zelensky’s party, is also an opponent. He has persuaded 20 of Ukraine’s 403 MPs to defect to his side. But his progress has stalled recently, with Ukrainian politicians reluctant to be drawn into political rivalry during the war.

There are rising stars among volunteers who supply weapons to soldiers, such as Serhiy Prytula, but they are staying out of politics for now. One man who is particularly loved and admired is Valerii Zaluzhnyi, the commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian army. Last year, a Ukrainian poll named him the no. 2 ‘politician of the year’ (winning 10 per cent of the vote to Zelensky’s 50 per cent). He shows no sign of political ambition, but it’s possible these military men will become more influential in the post-war years.

After victory, Zelensky may prefer a graceful exit to a Churchill-style defeat. For now, there is no domestic pressure to hold an election, which could be divisive at a time when the nation is battling for its survival. There is also the fact that to do so would require violating the constitution, which prohibits holding elections in a time of martial law. There are concerns that polling booths could become targets for Russian missiles.

If the pressure from America is great enough, it’s possible there could be an election next year. But to ask Ukrainians if they want to keep or reject their President while he’s fighting a war is to pose a question to which there will be only one answer.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in