Six years ago the ABC posted an article online about William Crowther, a prominent 19th-century Tasmanian politician, a statue of whom had stood in a Hobart park for 133 years. From that time, the statue’s fate was probably sealed, (‘Tasmania’s difficult history: Monuments leave out dark side to colonial past’). Last week the Hobart City Council voted to remove it because Crowther, who was a surgeon, had cut off the head of a dead Aboriginal man to send to England for research purposes.

At the inauguration of the statue the Hobart Mercury described Crowther as ‘a man of indomitable energy and courage, who was thorough in all his actions, whose philanthropy was broad, who devoted himself to the poor, the suffering, and the sorrowful, who found his happiness in doing the most good, and who did the most good when he did it not for money or reward. He was not a perfect man, but he strove after what he believed right’. Crowther’s philanthropy wasn’t enough to save him from the zealots on Hobart Council and, as reported by the ABC, ‘It will be the first time in Australia that a monument will be removed following pressure from First Nations people’. It almost certainly won’t be the last.

At the same time, and for remarkably similar reasons, in the USA, there is a raging controversy about the man after whom the Audubon society was named. John Audubon the naturalist, adventurer and author of The Birds of America, was very much a man of his times. He was involved in an amateur way in many branches of science. After a battle in 1836 between Mexican and American soldiers, Audubon decapitated several Mexican corpses and sent the heads to a notorious phrenologist who argued that different skull dimensions would prove the superiority of the ‘white race’ to all the others.

For Audubon, and for hundreds of other ‘scientists’ involved in this area of research, this was a standard way of practising science. But the fact that he made a major contribution to ornithological research and created one of the most famous books about natural history ever written, has not protected him the same sort of condemnation that Crowther is now experiencing. Audubon’s biggest sin was not decapitating dead Mexican soldiers. The reason why American ornithologists are up in arms about Audubon is because he owned slaves and opposed the abolition of slavery. The Audubon Society, which is one of the oldest and most successful charitable institutions in America, is now under tremendous pressure to change its name to remove the institution’s link with the racist Audubon. There are several statues created in his honour and, thus far, no one seems to want to remove then. The one at the Smithsonian Institute is 75 feet above ground and is therefore a bit safer than that of William Crowther. But there are several others throughout the USA and it is only a matter of time before activists decide to adorn them with red paint. In the meantime, as well as changing the name of the institution named after him, activists want to rename ‘Audubon’s Auriole’ and ‘Audubon’s Shearwater’, which were so named in his honour after he described them.

Gabriel Foley and Jordan Rutter are ornithologists who recently argued, in the Washington Post, that these bird names should not be allowed to continue as, ‘They are a memorial both to the colonial system that wove the fabric of systemic racism through every aspect of our lives – including the birds we see every day – and to the individuals who intentionally and directly perpetuated that system’. According to the two twitchers, we must remove the ‘stench of colonialism’ from our history.

However, it isn’t that simple. How are we to remove statues from parks, or alter the names of birds, without falling prey to the sin described by Orwell, in 1984, as ‘unpersoning’ someone? History is full of injustices against both individuals and groups but the injustices that attract activists today are almost always connected to race. Long after slavery had been abolished, small children were employed and exploited in coal mines and factories and as chimney sweeps in 19th century England. But mine and factory owners don’t seem to attract the same odium as the plantation owners. Hardly any of the thousands of people who walk up and down Castlereagh Street in the Sydney CBD, or who live in the suburb of Castlereagh, will know anything the English aristocrat after who those locations are named. But he has been described as ‘perhaps the most hated domestic political figure in both modern British and Irish political history’. His unpopularity stems partly from his association with the ‘Peterloo Massacre’. After his death by suicide Byron wrote;

Posterity will ne’er survey

A nobler grave than this:

Here lie the bones of Castlereagh:

Stop, traveler, and piss.

But Castlereagh, and his statues, are safe from the Greens, the BLM crowd and socialists in general, because the people who were massacred on the field at Peterloo in 1819 were white. They therefore had no obvious connection to the racism and colonial expansion that are seen by the left as the dominant feature of 19th-century England and therefore that massacre is not relevant today.

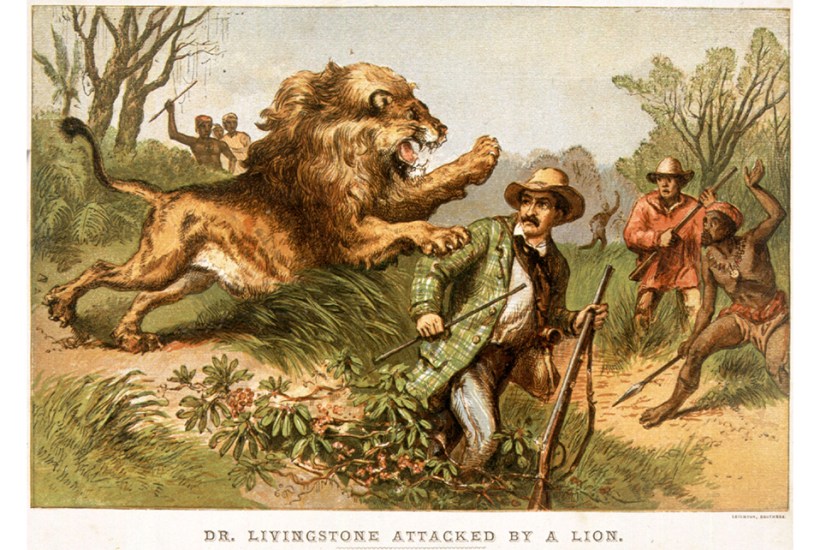

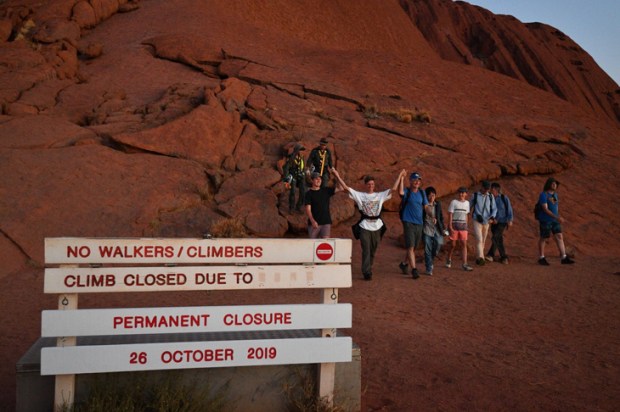

And this is what is completely wrong with the left’s current interpretation of history. In the middle of the last century, the teaching of modern history was concerned with the emergence of democracies in Europe and in colonies around the world or, to be more accurate, in some of the British colonies around the world. In the last six decades, the story of the arrival of the white man in the far-flung corners of the world has been completely reversed. No longer a story of heroic men like Livingstone bringing medicine and civilisation to the Dark Continent, it is now a story of racist white men oppressing native peoples who lived in peace with each other and were in harmony with nature. Both versions of history hold some truth and the tragedy of the current obsession with the left’s version of the impact of colonialism and racism, is that it is just as inaccurate as the imperialist paradigm it seeks to overthrow. Crowther’s statue should remain where it has stood for 133 years. By all means, provide a full account of his activities. But let it contain the truth.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in