President Zelensky has announced that he is dismissing the heads of all Ukraine’s regional military recruitment offices and replacing them with veterans who had served on the front line. He used a video address to say that a state investigation had turned up widespread corruption, including bribe-taking and help for draft dodgers to flee abroad.

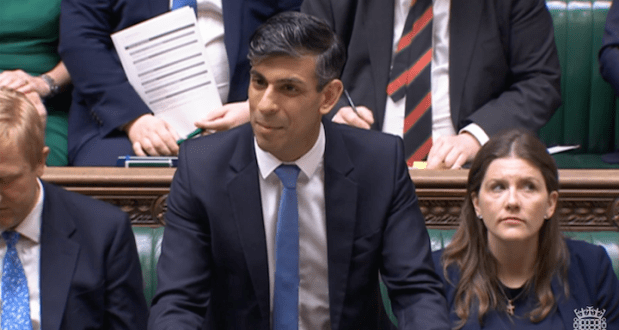

As a war leader, he has, in effect, autocratic power, beyond anything he would enjoy as an elected leader in peacetime – and he has shown himself willing to use it

Sounding a notably tough note, Zelensky said: ‘This system should be run by people who know exactly what war is and why cynicism and bribery during war is treason.’ He recommended recruitment officers who lost their jobs but were not subject to investigation should volunteer to fight while insisting that joining up would not free anyone from criminal responsibility. ‘Officials who confused epaulettes with perks,’ he said, ‘will definitely face trial.’

In one respect, Zelensky’s decision can be seen as the most pointed of his efforts to root out corruption, which was one of his election promises back in 2019 and is a theme that has surfaced intermittently during the war. But it is at least as significant for what it may say about the public mood and about how far Ukraine’s President is already trying to anticipate postwar Ukraine.

First, the public mood. It is hard to believe that Zelensky would have ordered a state investigation into recruitment, let alone across-the-board dismissals, had there not been substantial public disquiet about who is and who is not being called up to fight. Since Ukraine declared martial law after the Russian invasion, there has been a ban on most men between 16 and 60 leaving the country. But there are now noticeably more men joining their women and children outside the country, suggesting the ban may be less effective than it was.

The order also suggests that Kyiv may face some difficulty keeping up force numbers – for which there could be many reasons. The volunteer spirit, so evident and admirable in the first months of the conflict, might not be quite what it was; a number of viral social media posts show some recruiters resorting to extreme measures, reminiscent of press-ganging, to fill their quotas; or perhaps the casualty toll, for all that the numbers remain a state secret, is starting to act as a deterrent – a recent survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology found that 80 per cent of those Ukrainians asked knew of someone in their immediate circle who had died or been injured.

Whatever the reasons, for the President to sack all military recruitment heads in the middle of a war is a pretty drastic course of action and surely not something any commander-in-chief would choose to do if he thought that a lesser measure would suffice.

Second, though, there may also be a longer-term consideration behind Zelensky’s action. Whenever he or another senior Ukrainian official takes part in an international gathering, whether the Nato summit last month, or the G7 side meeting that followed, or the Ramstein meetings on military assistance, or the Ukraine Recovery Conference in London in June, there is invariably a subtext to what’s said on the western side. Those with experience of dealing with Ukraine are wary of corruption, having watched large sums of money simply disappear. Governments and potential private investors alike warn that Ukraine will have to clean up its act if it is to receive the massive help with reconstruction it will need, let alone qualify to join the European Union.

Now many in Ukraine, including in Zelensky’s immediate team, would regard that criticism as unfair. Between his inauguration and the Russian invasion, Zelensky probably did more to address corruption than any before him. New legislation was passed; a special anti-corruption court was established; dodgy government officials were dismissed. It can also be argued that the war has, in fact, served to reduce the power and influence of many so-called oligarchs, which might be seen as clearing the way for a less corrupt Ukraine.

So this is another reason why Zelensky may want to speak in harsh terms about corruption – to demonstrate his awareness of the scourge and his determination to address it. Announcing the sackings of military recruiters, for instance, he said that there were currently 112 criminal cases against recruitment officials in train, that some were taking cash and some crypto-currency, that ill-gotten gains were being laundered, and that people liable for military service were being ‘transferred across the border’. In other words, he wanted to show that he knew what was going on.

It will always be hard, of course, to distinguish how much is being made public out of necessity and how much is out of choice. Zelensky’s order of mass dismissals came after reports that the recruitment chief in Odesa had amassed millions in foreign currency and held a property portfolio in Spain. There are reports circulating about a scandal to do with the procurement and pricing of military uniforms. And back in January, a deputy minister for infrastructure, Vasyl Lozynskiy, was detained on suspicion of embezzlement, with other members of the ministry implicated and losing their jobs, too.

But there is a third aspect to the sackings Zelensky has announced, beyond the need to address public concerns about justice at home and his desire to reassure prospective donors abroad: does Zelensky have the authority, the actual power, to make these decisions stick?

As a war leader, he has, in effect, autocratic power, beyond anything he would enjoy as an elected leader in peacetime – and he has shown himself willing to use it. A small example was his recent summary dismissal of Ukraine’s respected ambassador in London for remarks he appears to have regarded as disloyal. For the time being, Zelensky’s position appears unchallenged. Nor does there appear to be anyone better equipped than he is to tackle Ukrainian corruption.

Even with his war powers, corrupt practices continue to be exposed. In the first months after Russia invaded, Ukraine’s military recruiters could rely on patriotic fervour to supply the numbers. Latterly, that became more difficult and they reverted to pre-war habits; bribery and corruption are back.

Zelensky has been careful to delegate responsibility for replacing the heads of regional recruitment. He has ordered the head of the military, General Valery Zaluzhny, to find the new batch of recruiters and the security services to vet them. But how effective will this be and how quickly can it happen? In announcing such a comprehensive purge, Zelensky is taking quite a risk. This is an issue of broad public concern in Ukraine and foreign donors – present and potential – will also be watching carefully. Zelensky’s success or otherwise could ultimately have a bearing both on his future and on that of Ukraine.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in