A-level results day is the most terrifying moment in anyone’s education. Poor GCSEs can be overlooked by a school that knows their pupils could do well in the sixth form. Degree classifications at university are so broad that one bad paper may well not matter. But A-Levels are brutal. Students who miss their university offer by just one grade in one subject can find themselves rejected without the right of appeal or the means to resit. Their future changes instantly by the barest of margins.

But the main problem with A-levels is that it’s not clear what they actually measure. We might like to think that grades reflect ability. They do, but there are far more variables at play. Hard work is one factor. The skill and experience of teachers are also part of the equation, but there is also luck. Students who spread their revision thinly can do well, but those that target their efforts might do very well indeed if they guessed right.

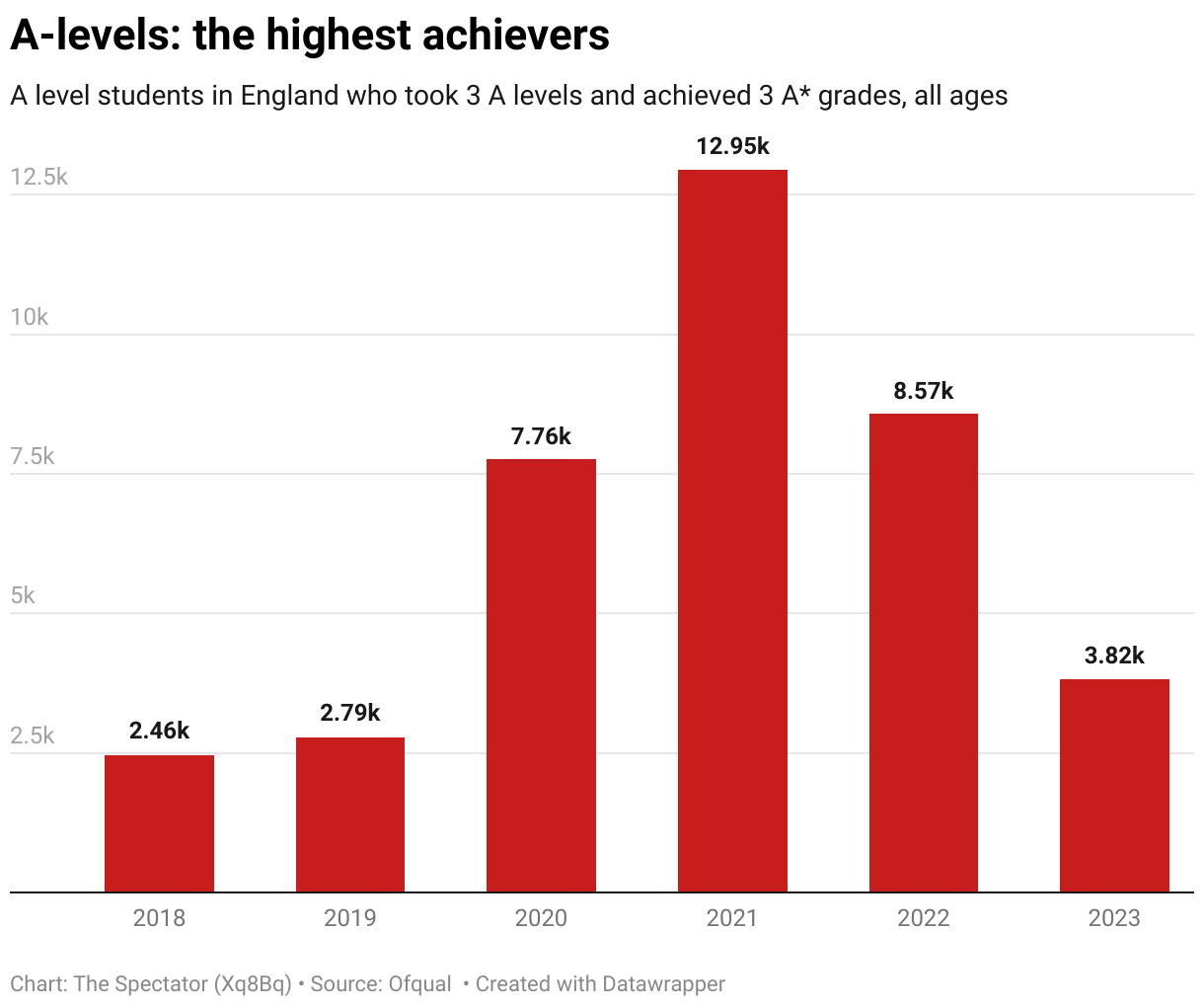

There is also the year they happened to be born. My own A-Level grades (AAB incidentally) were good enough for me in 1986. Off to Newcastle I went to study Astronomy and Astrophysics. My pupils are sometimes aghast: ‘But Dr Hayton, you didn’t even get an A* in physics?’ I’m beginning to show my age when I point out that there were no A* grades back then, and my B is probably worth at least an A-double star these days. There has been no consistency over time. An A* in 2019 measured something very different to an A* in 2020 and 2021 when teacher predictions replaced exam grades.

There’s also a myth that the class of 2023 cohort didn’t face as much disruption as their predecessors. They didn’t sit their GCSEs either – so A-Levels are their first experience of public exams – and they were sent home for the delights of online learning (or not) during two crucial terms in Years 10 and 11. They have an argument for a leg-up. However, for them, 27.2 per cent of A-Level entries were graded A* or A – a big drop from the 36.4 per cent recorded last year.

But according to the Joint Council for Qualifications, we really ought to be comparing with the statistics from 2019, when only (!!) 25.4 per cent of entries reached that benchmark. So, are pupils doing better or worse? And, if we can answer that question, what exactly are they better or worse at?

In reality, an A-Level grade measures just one thing – how well the student could answer a specific set of questions on couple of days in the summer. Every year we do this to our children, almost as a rite of passage to adulthood, and every year I wonder what purpose it might possibly serve. Or I used to. Until 2019 I would have suggested that an open and honest end-of-school report might be more meaningful to universities and employers. We might be able to praise all the achievements of our pupils and perhaps point out their shortcomings.

But then came the pandemic. I regret the fact that schools were closed – especially the second closure in the spring of 2021 – and the cancellation of exams in 2020 and 2021. But if those two years proved anything, it was that when teachers had the opportunity to influence the results, the results improved far too much.

So maybe A-Level exams are the least bad option. It’s hard for children, but giving more power to the teachers has increased a sense of unfairness. Beyond university, however, we should maybe pay less attention to the grades that 18-year-olds are staring at today. There is more to life than AAB.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in