Andrew Martin is in love. Head over heels in love, quite unable to control himself in his appreciation of the object of his affection, which is, believe it or not, an underground railway network. While this may seem an irrational attachment, it becomes easier to understand as his account of the origins, history and, most importantly, design of the system unfolds. ‘What most distinguishes the Metro,’ Martin tells us, ‘is its beauty.’ Its eroticism is, too, ‘expressed in diverse ways’, notably condom machines dotted around the system, advertisements for vibrators and the revelation that Ticket de Metro is ‘the name of the most popular bikini wax among Parisian women’.

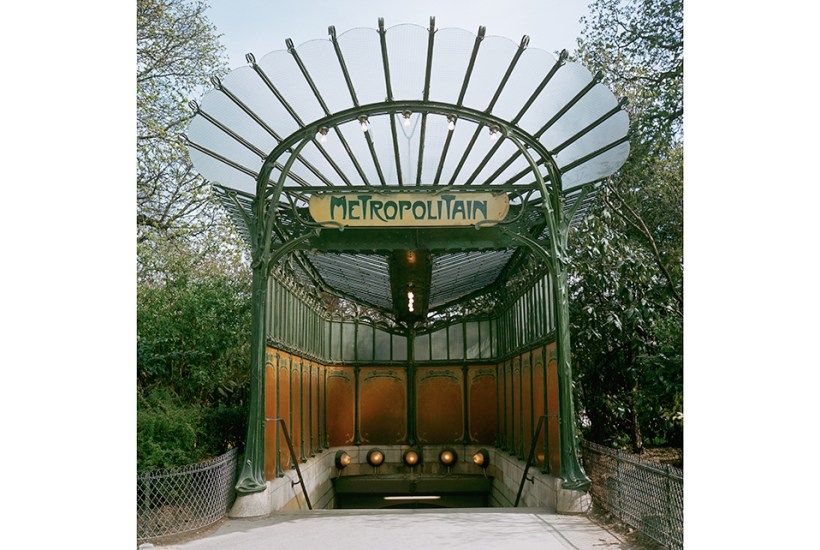

In fact there is something very special rooted in the origins of the Metro which differentiates it from other underground systems. One of the early proponents of the network, Charles Garnier, the architect of the Paris Opera, wrote that the Metropolitain would be accepted by Parisians only if ‘it rejects absolutely all industrial character so as to be completely a work of art’. The network does indeed reflect this ideal, as Martin describes, with its elegant entrances (unencumbered by names, as all Parisians apparently know where they are), smart, white-tiled stations and a blend of styles – Art Nouveau mixed with Romanticism and a soupçon of Modernism. This emphasis on elegance was initiated by the Art Nouveau architect Hector Guimard, who designed all the early Metro entrances, and while many of these have not survived, the emphasis on style has.

Of course as an Englishman, albeit from Yorkshire rather than London, Martin feels the need to emphasise the differences between the London Underground and the Metro, holding that the latter is, quite simply, superior. He obviously likes the Underground, having written a couple of books about it, but in a dispassionate, rather routine sort of way, in the manner of a long-term relationship that has gone stale. The Metro, on the other hand, is his French lover with whom he can find no fault. He seems to be able to recall every journey he has ever taken on it in fine detail, lacing his account with descriptions of the random Parisians he has come across on the way.

This is a cleverly structured book, eschewing the obvious chronological order in favour of a series of themes, capped by a section on the histories of each of the individual lines. And there is detail to liven up every page. Martin’s knowledge of the films and books featuring the Metro is encyclopaedic and always entertaining. Virtually every major French figure in the arts, from Johnny Hallyday and Brigitte Bardot to Georges Simenon and Jean-Luc Godard, gets a mention. There are literary or cinematic references throughout, and Martin has worked hard to ascertain the exact location of each reference, taking great pleasure in finding mistakes and exposing instances where the protagonists have made impossible connections.

If the London Underground looms as a constant but largely silent backdrop to his descriptions of the Metro, he deftly avoids the trap of making too many banal comparisons. Those differences are profound, as they reflect wide cultural and social issues. The Metro was designed from the start by public-sector planners as a network for a state-owned entity in the first years of the 20th century; the Underground was developed by a plethora of private companies competing with each other. The first half-dozen lines of the Metro were completed within a decade by the system’s first engineer, Fulgence Bienvenüe, a romantic classicist, which again is reflected in the style of the system. It is a much more intensive one, with stations hardly ever as much as a kilometre apart – from the platforms you can often see the next one down the tracks – and it is far shallower, with steps rather than lifts or escalators being the norm.

Apart from the Parisian transport provider, the RATP, there was a rival, the Nord Sud, which developed a couple of the lines, but these were soon absorbed into the larger network. The way the system grew, and is still growing, is again in sharp contrast to its London counterpart. Throughout the Metro’s history there have been regular additions of stations and sections of line at the outer limits. Now, however, incremental change is being replaced by a massive expansion, with four new lines encompassing an extra 68 stations and 200 kilometres of track, largely in the suburbs.

There is just one lacuna in Martin’s wonderful romp with his lover: the absence of a map. I know we could all look it up online, but a couple of pages devoted to a representation of the system – which has now been schematised in the manner of Harry Beck’s ground breaking map of the London Underground – would have helped us navigate our way around the system with him.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in