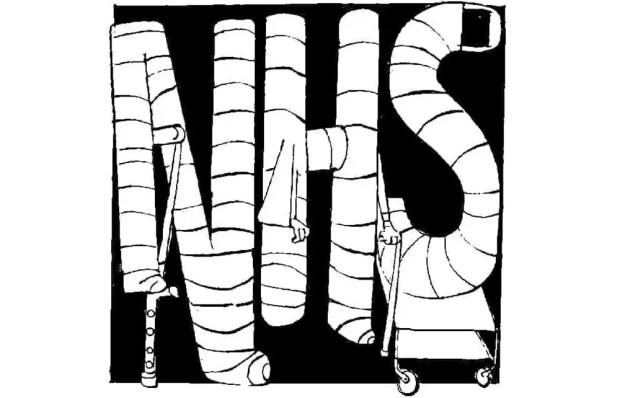

No one who has paid any attention to NHS scandals over the past few decades should be at all surprised by the way in which managers at Lucy Letby’s hospital repeatedly dismissed concerns about her. When worried consultants produced considerable evidence to show that the nurse was present at every single event where a baby had dramatically collapsed or suddenly died, they ended up being the ones in the firing line. Management even forced them to apologise to Letby personally at an HR meeting, to which, bizarrely, the nurse brought along her parents.

Yet in the NHS, monumental managerial failures are not unusual, they’re typical. In the independent inquiries into all NHS disasters of recent years, such as Mid Staffordshire, Morecambe Bay and Shrewsbury and Telford, there is one common theme: the managers got in the way of those trying to get to the truth. From scandal to scandal, nothing seems to change.

NHS managers are often the bogeymen in healthcare. Clinicians love to denigrate their clipboard-clutching overlords. The only time I’ve ever heard someone booed at a church service was when I was in a congregation that was stuffed to the rafters with doctors from the local NHS hospital and a young woman stood up to say she was an NHS management trainee. And if you want to get a few cheap cheers as a politician, you can call for the managers to be abolished – as Liz Truss did when she was campaigning for the Tory leadership last year. In fact, it was Truss’s heroine, Margaret Thatcher, who brought in general management to the NHS after discovering that no one was effectively in charge of hospitals.

On paper, when compared with many more effective health systems, the NHS is actually quite under-managed. If you include administrators as well as executives, managers make up around 27 per cent of all staff in the health service. But those figures tell us nothing about whether the management culture is any good.

It isn’t. It is hard to find anyone working in the health service who doesn’t think it has a problem with bullying. The origins of the management bullying culture lie in those Thatcher reforms of the 1980s. Shocked by a rise in the number of people working in the NHS, the then prime minister commissioned Roy Griffiths of Sainsbury’s to review how the service was actually being run. He came back to her with the conclusion: ‘If Florence Nightingale were carrying her lamp through the corridors of the NHS today, she would almost certainly be searching for the people in charge.’

What followed was the introduction of general managers, something contested at the time by healthcare unions, who felt their members should be the only ones eligible to run a hospital. Very few clinicians ended up in general management, in part because of the hostility of their organisations to the reforms, but also because the NHS became obsessed with hiring people from outside, on the basis that they would have a better perspective on what was going wrong. That led to a ‘them and us’ attitude that persists today. Doctors are suspicious of the calibre of the people managing them, and the managers are often on the defensive. It’s not hard to see how that dynamic made the conversations between doctors and managers at the Countess of Chester hospital much harder.

Standoffs between the two groups are a regular feature of NHS life. One manager at Guy’s hospital recalled to me that ‘to save money, managers literally locked – chained and padlocked – some operating theatres to stop some of the cardiac surgeons operating’. Some managers didn’t know how to manage: one administrator from the early years of general management in the 1980s says that many of his colleagues behaved as though they were on a City trading floor, while another remarks that they couldn’t cope with the level of accountability they were supposed to take on: ‘Because people were now responsible for failings, they were frightened of those failings being spotted at all. It wasn’t healthy, isn’t healthy.’

The New Labour years were in many ways bountiful for the NHS. There was higher spending and a lot of political attention directed at neglected hospitals and wards. But the bullying culture only worsened. Some of it was exported from the world of politics, which was going through a macho period of control freakery. The desire to see results for the extra money meant there was a relentless focus on meeting targets, to the extent that an invitation to sit on the health secretary’s sofa became as infamous as a boat trip to Traitors’ Gate. Alan Milburn was then in charge of the sofa of doom. One executive remembers: ‘You didn’t want to be invited to sit on the sofa in his office. Because it was heading for him shouting at you and using really foul language.’

What all these managers, from the very top of the organisation down to individual hospital wards, were frightened of was the statistics making them look bad. It wasn’t a fear of not learning from mistakes so that catastrophes only happened once. It wasn’t whether patients and their families were suffering or unhappy with their care. It was about the person above them coming down to shout. No wonder executives at the Countess of Chester resented the push from doctors in Letby’s unit to examine why babies kept dying without warning: there was no incentive to uncover a scandal at the hospital.

The political row at the moment is whether the Letby inquiry will be a public one or a quicker non-statutory one. There are lots of arguments in favour of giving the inquiry the sort of powers that come with a statutory footing, including witnesses giving evidence under oath. The bigger problem will come once that investigation has reported. It may well be full of ideas, maybe even regulation of managers. But if previous inquiries are anything to go by, nothing will really be done – and we will have to wait for the next scandal.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in