In 1889, Raffaele Esposito, the owner of a pizzeria on the edge of Naples’s Spanish Quarter, delivered three pizzas to Queen Margherita, including one of his own invention with tomatoes, mozzarella and basil, their colours taken together resembling the Tricolore. The Italian queen loved the pizza, and Esposito duly named it after her. In that restaurant today hangs a document from the royal household, dated 1889, declaring the pizzas made by Esposito to be found excellent by the queen.

And so was born the Pizza Margherita, a dish now synonymous with Naples. The queen’s seal of approval in the wake of Italian unification, which had proved difficult for Naples, came to represent the embracing by the governing royal family of an impoverished city by way of their cheapest street food. It showed the royals to be down to earth, and the Neapolitans to be part of a larger Italian nation.

It’s a good story, but it’s also little more than that. The ‘custom-made’ patriotically coloured pizza was well known before 1899, the pizzaiolo in question was not the celebrated chef he is now made out to be, and there is no evidence of the queen trying these pizzas, let alone endorsing them. But that hasn’t stopped the Margherita becoming something that has put Naples on the culinary map, a place which people travel to just to taste authentic pizza. And it doesn’t mean that proper Neapolitan pizza isn’t exceptional. So does it matter if it’s founded on an urban legend?

In National Dish, Anya von Bremzen sets out to understand the link between food and national identity, and what symbolic dishes can tell us about national cultures. ‘We have a compulsion to tie food to place,’ she says. She travels across six countries (France, Italy, Spain, Turkey, Mexico and Japan) in an attempt to unpick the belonging, pride, unification, essentialism and political manipulation that go into their emblematic dishes. As well as pizza and pasta in Naples, she tries to find authentic pot-au-feuin France, the meaning of ramen and rice in Tokyo, the origin of tapas in Seville, the future of mole and tortilla in Oaxaca, and the significance of meze in Istanbul.

Many of these dishes have been granted Unesco’s intangible cultural heritage status, an acknowledgment that there is something distinctive about a way of cooking or eating that is inextricably associated with a geographical place and people. The ‘gastronomic meal of the French’ has been recognised as a ‘marker of cultural identity’, as have Washoku, the traditional dietary cultures of Japan, and the art of making a proper Neapolitan pizza. In 2017, Azerbaijan was granted the status for its ‘dolma-making and sharing tradition’, which caused consternation in Turkey and Armenia, countries that also lay claim to the stuffed leaves.

Of course, these kind of statuses, which are designed to preserve cultural heritage, give rise to questions of ownership and identity. ‘As the world becomes even more liquid, we argue about culinary appropriation and cultural ownership, seeking anchor and comfort in the mantras of authenticity, terroir and heritage,’ von Bremzen writes. The initial questions she asks are simple ones: how and why do dishes get anointed as ‘national’, and what is the connection between cuisine and country?

She approaches the exercise with understandable scepticism. She grew up in Soviet Russia before fleeing to the US with her mother when she was ten, so she is no stranger to top-down nation-building and knows the political power that food can have in this.

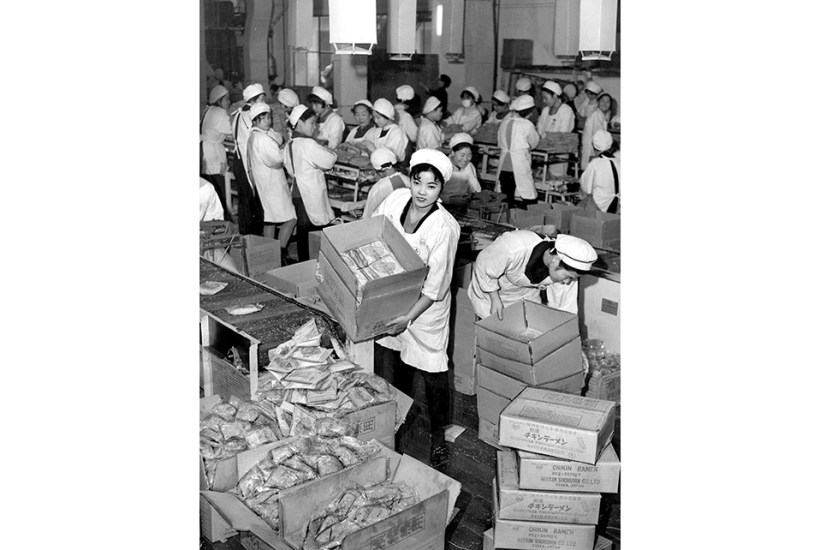

The scepticism is well-placed. After her pursuit of the cult of pot-au-feu is mostly received with Gallic shrugs, and pizza’s origin story turns out to be ‘fakelore’, she discovers that tapas is also a recent invention, only entering the dictionary in 1936 and primarily used as a way to entice tourists. In Tokyo, she finds that the popularity of ramen was manufactured in order to use up US wheat flour imports during the post-1945 occupation. The Japanese ministry of health and welfare ran campaigns to push wheat, and therefore noodles: ‘Parents who feed their children solely white rice are dooming them to a life of idiocy.’ What we think of as intrinsically Japanese is a recent adoption and a product of propaganda.

This set-up feels as though National Dish could be a particular type of travelogue – a food memoir, with some local cookery lessons and nice anecdotes about the passion people have for traditional dishes included, plus a bit of smugness when their myths are debunked one by one. But that’s not what it is. For all its dry wit and vivid descriptions of puttanesca and tortillas, this is a serious book – a skilful blend of academic research and lived experience. It’s a sparklingly intelligent examination of, and a meditation on, the interplay of cooking and identity.

If you’re looking to connect food to identity, Seville provides a perfect illustration. ‘Jamon is the symbol of Spain,’ a ham vendor tells her. She duly visits producers, learns about the craft and tradition of grazing pigs and hanging hams and eats quantities of the ‘slow release endorphin-bomb’ that is ‘pure pleasure’. But it’s never that simple. It is inescapable, she learns, that the ‘cultivation of Iberian ham is tied to… the triumph of Christianity over Islam’. Pork products were used during the Inquisition to root out those who had not truly converted from Judaism or Islam: cooking pots were examined and reactions to bacon scrutinised, with a wrinkled nose at rendering lard enough to alert suspicions. And, of course, the consequences were grave.

That jamon simultaneously inspires national pride becomes central to von Bremzen’s understanding of national dishes. When we hear simple, neat stories about the national importance of a dish, they are usually hiding something. But problematic histories don’t necessarily negate the cultural value of the dish. The two can coexist. ‘Jamon, it’s muy nuestro,’ says one of the guides – ‘so ours’.

In Mexico, the author grapples with the double-edged sword of this idea of culinary identity. During her time there, locals emphasise the importance of corn. She is constantly told: ‘Somos gente de maiz, sin maiz no hay país’ – ‘We are people of the corn, without corn there is no country.’ But when she is shown how laborious the process of tortilla-making is, how physically damaging, how it is the responsibility of women, how technology is shunned in favour of authenticity, and how, even in the general context of Mexican poverty, incredibly badly paid it is, she struggles with whether this corn identity represents empowerment or slavery.

In all these encounters, the fact that von Bremzen is an outsider is helpful. It allows her to ask questions, to try things and get them wrong and to be even-handed. But as she comes to the end of her narrative, Putin invades Ukraine and, amid the horror of the war, she is forced to confront her Russian identity, and the dishes – specifically borsch – bound up in it.

The general conclusions shereaches in the book are unsurprising: food is political and personal; in an age of globalisation, an attempt at ownership, of distinctive identity, is understandable; and the interplay of these factors are complicated and often cause power imbalances. These are really set up in the premise. But von Bremzen’s flair for bringing places and people to life, her combination of wit, enthusiasm and curiosity and her careful research and genuine thoughtfulness make National Dish new and compelling.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in