Readers would doubtless find it hard to believe that the late Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh kidnapped and killed indigenous children while on a state visit to Canada in 1964. Yet this story circulated for years in Canada along with other horror stories of the rape, torture and murder of indigenous children at the hands of depraved priests and nuns. The bodies, it was said, were thrown into furnaces or secretly buried at dead of night. These accusations were linked to boarding schools run by various religious bodies first established in the 19th century and finally closed in the 1990s. A Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up in 2008, and millions of dollars were given by the government to search for clandestine mass graves. None was found.

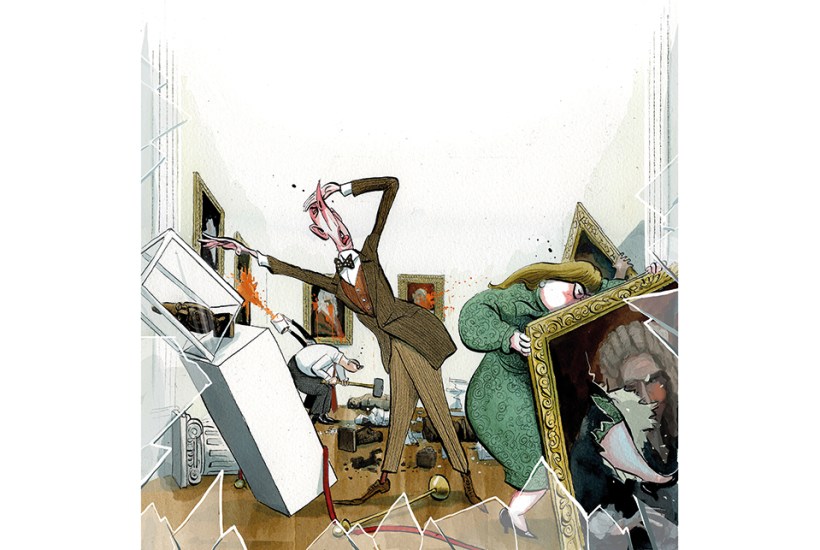

Then, in 2021, a single survey of an orchard at Kamloops in British Columbia by a young anthropologist using ground-penetrating radar found ‘disturbances in the ground’, and this was taken as proof of a mass grave of hundreds of children. Soon other communities announced that they too had found forgotten cemeteries, and the media portrayed these as hidden mass graves, implying terrible crimes. Canada descended into a frenzy of allegation and public self-flagellation. Dozens of churches were vandalised or burnt down, and the Trudeau government ordered the national flag to be flown at half-mast for several months. The Pope apologised, as did the Archbishop of Canterbury. China denounced Canada at the UN. But no investigation has been made of the site at Kamloops and no bodies have been found there.

Yet sensationalist stories of abuse and murder have gained credence in official circles, or at least are not publicly contested. Investigation is hampered by a reluctance to hint at scepticism concerning accusations (‘survivors’ truths’) made by members of indigenous communities, who insist that inquiries should be led by indigenous people and their ‘Knowledge Keepers’, not by the police. The highly activist Nationalist Centre for Truth and Reconciliation took control of much of the documentary evidence, which it has been unwilling to show to researchers.

A moderate view would be that these schools were often sites of harshness and neglect, but there is also plenty of evidence of happy children and dedicated teachers. The schools were often asked for by local indigenous communities. There is no proof of children being kidnapped and forced into them. Many were close to their homes and supported by their parents. Even in the recent past, nuanced discussion of the schools was possible. No longer. Those indigenous leaders who formerly praised their own school experiences are silent. The official story focuses solely on horrors.

Nevertheless, several prominent – and in the circumstances, brave – Canadian historians have expressed reasoned doubt. Careful record-keeping means that suggestions of thousands of missing children and unexplained deaths can be disproved. Old cemeteries that have lost their grave markers have been identified, but still no secret mass graves have been found.

Far from there being relief that the most appalling fears appear groundless, a deadening cloak of silence has been thrown over the whole subject. The former executive director of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is pressing for an ‘anti-colonial approach’ making ‘denialism’ subject to ‘both civil and criminal sanctions’. The justice minister says that he is open to the idea. The deliberate vagueness is doubly intimidating. Would asking for the radar scans at Kamloops be ‘denialism’? Or pointing out that no human remains have been uncovered?

We are used to ‘denial’ of some controversial assertion being proclaimed a moral and intellectual offence. As far as I know, though, only Holocaust denial is a crime in some countries. Note the obvious difference: evidence for the Holocaust is overwhelming and denying it in good faith impossible. The situation in Canada is precisely the opposite: it is not denying but rather sustaining these accusations in the absence of evidence that tests good faith.

But there is a lot of money at stake. Hundreds of millions of dollars in compensation have been handed out to former school children. Ideology too: the schools symbolise a policy of integration – broadly followed until the 1960s – when full citizenship was offered to indigenous peoples, as opposed to the present policy of maintaining them as separate ethnic groups in territorial reservations. Integration is now tantamount to genocide for many liberals, so accusations that schools were literally ‘institutions of genocide’, killing and secretly burying ‘thousands of children’ is too powerful a story to be given up by those pursuing greater land rights, huge reparations and ‘rewriting national history’ to promote separate nationhood.

Britain’s ‘history wars’ are small beer by comparison: a statue toppled here, slogans scrawled there, misleading information given by our great museums. Nevertheless, comparable processes can be seen on both sides of the Atlantic. Allegations of historic British iniquities are given automatic credence as institutions, whether through genuine belief or moral panic, hasten to acquiesce. Objections based on careful interpretation of evidence are almost invariably ignored.

In 2019 Britain had its own burials scandal, when a Channel 4 programme made by David Olusoga and presented by David Lammy MP charged the Imperial War Graves Commission with wholesale racism in its treatment of the bodies of non-white first world war soldiers, practising ‘apartheid in death’. Olusoga added on the BBC that Winston Churchill had ‘deliberately signed off’ on this policy. A presumably panicky Commonwealth War Graves Commission produced a report accepting the claims and deploring the ‘pervasive racism of contemporary imperial attitudes’. A no less panicky Ministry of Defence expressed regret, and Boris Johnson rounded it off by saying he was ‘deeply troubled’ that ‘not all of our war dead were commemorated with equal care and reverence’.

Did any of them feel a duty to protect the reputation of their institutions and of Britain itself, rather than giving a green light to international accusations, including by China, of British racism? Apparently not. But Professor Nigel Biggar at Oxford did examine the evidence, and found that ‘the Imperial War Graves Commission… was committed to the principle of the equal treatment of all the Empire’s fallen troops… whatever the colour of their skin’.

The war graves claim, like the Canadian allegations, was intended to create a scandal on a deeply emotive subject. When many ethnic minority groups are eager to emphasise their participation in Britain’s wars as a buttress to their rightful claim to full national membership, the accusation that the bodies of their dead soldiers were disrespected is particularly hurtful and damaging.

Though ‘denialism’ is not yet illegal, academics such as Biggar who contest orthodoxy are sure to be publicly reviled by gaggles of their colleagues who try to intimidate and silence them. Attempts were made to sabotage his research project on the ethics of empire. Those of us old enough to be untouchable can speak our minds, but younger colleagues often tell us shamefacedly that they are constrained by concern for their careers. They may be ostracised, seeing invitations to speak dry up, research funding applications fail, book contracts get cancelled and the fruits of several years’ work end up destroyed.

The orthodoxy in schools, in museums and on television is always the same: Britain was racist in the past, and so it is racist today. Producing evidence that this is untrue or exaggerated is heresy. So when the independent Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities, set up by Kemi Badenoch as equalities minister, reported in 2021 that ‘most of the disparities we examined… often do not have their origins in racism’ it was met with a flood of vitriol from activists. No matter that an earlier report by the EU and a later one by King’s College London reached similar conclusions: that Britain was among the least racist countries in Europe. Here, as in Canada, distortions of the past serve to create a distortion of the present.

The Canadian case shows this in lurid form. Accusations of genocide and child murder, combined with threats of punishment for ‘denialism’, make whole areas of public policy impossible to discuss dispassionately and create a poisonous victimhood culture. The Canadian government is reported to spend as much now on subsidies to its indigenous minority as it does on defence. So huge interests are involved. Is the money properly spent? Is the policy of keeping certain ethnic groups largely dependent on welfare and with limited life choices either effective or ethical? The same questions could be asked in the US and Australia. But in all three countries, rational consideration is blighted by induced guilt about the past.

What is at stake is not only intellectual freedom and unconstrained academic research, though these are certainly important enough. Even more important is the ability to conduct honest public discussion, examine policy and assess the true state of the nation. Those who try to stifle investigation are intent on manipulating our view of the past and creating myths and taboos to control power and policy in the present. Dispassionate historical scholarship can serve political rationality by contesting extreme or groundless claims. But such scholarship is under threat.

Settler societies have the grave problem of dispossessed indigenous minorities which we do not. For that reason, ‘history wars’ in America, Canada and Australia are far more serious and potentially damaging than in Britain. Nevertheless, even here we risk encouraging a new generation to regard its country and its history as sources of shame, guilt and resentment. The real achievements of integration risk being undermined. And Putin can gleefully denounce the West’s ‘colonial crimes’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in