Albrecht Dürer, one of the most narcissistic artists that ever lived (and it’s a crowded field), would have loved this book. It lays out methodically, with academic brilliance, the marketplace, techno-aware basis of the ‘Dürer Renaissance’ and the artist’s rise to immortal fame. With a glorious accumulation of detail, assiduous research and – as she acknowledges before her exciting journey begins – the benefit of ‘magnificent institutional support’, Ulinka Rublack, a history professor at Cambridge University, delivers a deluxe book, with chapter and verse to support her grand subtitle: ‘Art and Society at the Dawn of a Global World’.

Dürer (1471-1528) is a time-travelling artist who has weathered every movement and twitch in sensibility. He has inspired devotion, from John Ruskin, who celebrated ‘Albert’s’ deathday as a kind of personal communion, to William Morris and George Bernard Shaw, who covered their walls with his prints; from the modernist poet Marianne Moore, who walked into the Met in New York in 1928 and professed herself to have fallen in love with him, to Andy Warhol who had Dürer’s praying hands carved on his tomb (you can see them on a camera perpetually trained on the cemetery). Those hands also turned up on the cover of the rapper Drake’s 6 God album in 2015, just as Dürer’s dinosaurean woodcut of a rhino appeared on the label of an Italian white wine I drank on Nantucket when writing my own book about the artist’s mythic, and Ahabian, attempt to draw a stranded whale.

Rublack’s book is not concerned with myth, or even really with Dürer’s art. It boasts 69 lavish illustrations, but only ten are of works by the artist. Surely some of those magnificent institutions could have coughed up the repro fees for the sexy embrace of Dürer’s lifesize Adam and Eve, who look as if they’ve just stepped up to the edge of a Tuscan swimming pool; or, indeed, for his glamorously vain self-portrait, having returned from Italy in 1496, dressed to the nines, with a mysterious lock cut out of his famously oiled, curled hair. Even academia deserves some eye candy every now and then.

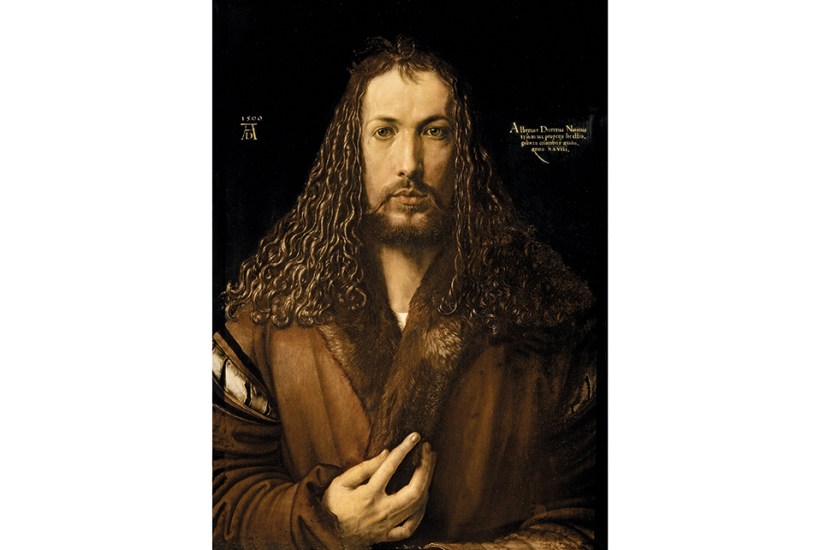

But we do get a splendid plate of Albrecht-as-Christ in 1500, fixing us with his eyes, although not the fact that, by creating a triangle with that waterfall of hair and holding his fingers in the shape of a ‘D’, Dürer has actually painted his monogram – a Warholian first fixing of the artist as a cult of himself.

With her unerring eye, Rublack contributes fantastic details of how the hair was curled with egg white, how Dürer kept a book of secret recipes for how to write with gold and soften glass with a ram’s blood, and even intended, true Renaissance man that he was, to create a medicine to heal wounds. As Rublack argues, his was a world moving out of the medieval into the modern. Dürer’s concoctions may have seemed more alchemical than scientific (one might say the same about the miracle of his paintings and engravings), but he was remorselessly looking to the future, to the extent that he experienced passionate dreams about what artists would accomplish 500 years later.

Rublack’s great academic take, her USP on Dürer’s story, is to show that trade and technology – Vorsprung durch Technik: the artist’s home town of Nuremberg boasted 100 printing presses – enabled him to become the man whom the critic Laura Cumming has hailed as ‘the first truly international artist’. It helped to have friends in high places. Dürer’s official patron was the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian and his best friend, Willibald Pirckheimer, was an influential intellectual and serial womaniser. In Rublack’s telling, the two men are always comparing their sexual conquests, although she only mentions in passing that these ‘might have included homosexual relationships’ – a somewhat prudish note, given that Dürer’s greatest biographer, Erwin Panofsky, noted back in the 1930s Albrecht’s evident predilection (in countless drawings and engravings) for well-endowed young men.

The book focuses on three merchants and tastemakers who either commissioned or befriended Dürer or whose careers echo Rublack’s themes. Pre-eminent is Jakob Heller, whose family were so rich they had a currency named after them. (They also had a coat of arms with a lobster on it, but sadly this isn’t explained.) It was Heller who commissioned the altar panels Dürer painted in 1507 – the ‘lost masterpiece’ of the book’s title. Rublack amusingly reports Dürer’s pleas to Heller (largely disregarded) for a suitable reward for all the time he’d spent on the work. Almost in revenge, he depicts himself into the central panel of the altarpiece holding a placard declaring ‘I painted this’ as an uncondoned advertisement both for his talents and for his new fur coat.

Hans Fugger is the second of the trio, the scion of one of the richest non-royal families that ever lived. He was as keen on collecting art as he was on feeding himself delicacies: freshly painted rolled-up canvases would arrive at his schloss as if ordered online, packed in the same consignment as spicy sausages from over the Alps.

The third person is Philipp Hainhofer, an art entrepreneur feeding a new desire for exotic objects. These ranged from ‘Indian clothes and feather-work’, possibly Meso-American in origin, to the gazelle horns, sharks’ fins and corals that Dürer would acquire by bartering his prints for precious specimens. Dürer looked in envy at Margaret of Austria’s collection, which included the ‘very large tooth of a wild boar of the sea’ – either a walrus tusk or the tooth of a sperm whale.

In a lovely section on Wunderkammern, private proto-museums, Rublack describes how seashells were carefully polished to make them look as they did underwater, ‘rather than dried and dulled by air’. Everything was about sheen and veneer. These glimpses validate her theory that Dürer could not have flourished as an artist without such patrons. In this time of new consumerist luxuries, he busily sourced, or stole, delights from the old and new world.

The fact that we know so much about Dürer is partly due to the survival of his journal of a year-long journey he made to the Low Countries, fleeing a plague-haunted Nuremberg before its lockdown, drinking and gambling with his rich, titled friends in Antwerp and Brussels. But 400 years later Dürer would drive Roger Fry demented with his obsessive accounting of how much everything cost, from his passport to his socks.

Fry’s Bloomsbury rationality had no time for such mundanities. He would surely have thrown Rublack’s book across the room. Albrecht, on the other hand, would have picked it up, lingering lovingly over every detail of who bought what, when and how – the material proof that he had staked his place in art history five centuries ago.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in