‘Thirteen wasted years’ bellowed Adolf Hitler at receptive audiences in the spring of 1932. He was talking about the first full German democracy, the Weimar Republic. Proclaimed in November 1918, it was born out of a desire to do things better after the horrors of the first world war and was an ambitious attempt to establish one of the most progressive states in history. ‘Democratic chaos,’ sneered Hitler, ‘unmitigated political and economic chaos.’ Much of the electorate agreed. Less than a year later, Hitler became chancellor and immediately set about fulfilling his electoral promise to destroy democracy.

The short and tumultuous story of the Weimar Republic continues to fascinate. The globally successful Babylon Berlin, set in the last years before Nazi rule, is said to be the most expensive non-English TV series ever made. When there is a sense of crisis in politics, journalists often speak of ‘Weimar-isation’, the term evoking concern, upheaval extremism and unease.

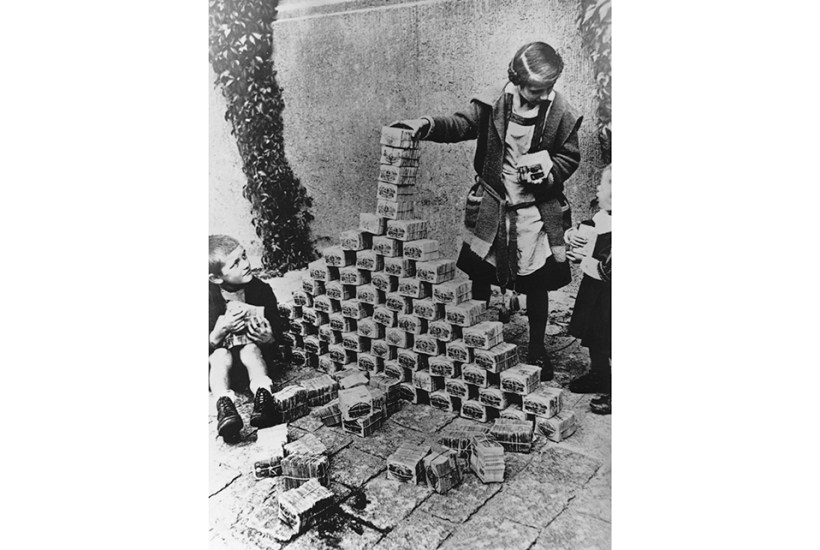

Weimar’s interest partly lies in the fact that it seems so very familiar: women had democratic rights; there was political infighting, inflation and deep societal division; there were radios, cars, cinemas and planes. Yet it also represents a twisted version of our reality with its twitching, war-marked veterans, its intense street violence and its backdrop of perennial cynicism. Weimar acts as a dark mirror to modern democracies, disturbingly absorbing for its spectacular fall from the heights of liberalism to the depths of Nazi tyranny.

Frank McDonough sets out to tell this dramatic tale in full. An expert on the Third Reich, he now presents a prequel to his two-volume work The Hitler Years. The Weimar Years offers a systematic narrative history that begins in the blood-soaked trenches of the first world war and ends with Hitler’s triumphal accession to the chancellorship in January 1933. The vastness of the available material is tackled with admirable scholarly discipline. The chaos of Weimar’s political parties, its rich cultural landscape and the bewildering speed of events are parcelled into 15 digestible chapters, one for each year, with beautifully reproduced images evoking the faces and places of the era.

Germany’s fractious parliamentary history throughout these years is described in detail, from the ultra-democratic but flawed constitution to the many individuals who sought to undermine the system. The author highlights the difficult preconditions that burdened the fledgling democracy, but shows that even if Germany had been blessed with a perfect legal framework and the goodwill of all involved, it lacked the societal cohesion to find the compromises necessary for functional politics.

The country couldn’t even agree on the colours that would best represent its new character. The right wanted to retain the imperial black, white and red flag, while the liberals and Social Democrats thought a rebrand was required. They wanted the black, red and gold tricolour that symbolised the liberal nationalism of the 1848 revolutions which had failed at the time to unify Germany under a democratic constitution but seemed to represent the appropriate spirit. While the constitution proscribed the liberal tricolour, the issue remained acrimonious, with paramilitary organisations marching under different banners in the streets. In 1920, Hitler opted for the imperial colours with the swastika at the centre as the flag of the Germany he imagined. The conflict caused a cabinet crisis in 1926 when it was suggested that German embassies and diplomatic missions abroad should be allowed to fly the old flag alongside the new.

Such squabbles were unpleasant and debilitating, but they were nothing compared to the bitterness of politics in general. More than 350 people were assassinated between 1919 and 1923 alone. These included the foreign minister Walther Rathenau, who was gunned down in an open-topped car in broad daylight; the communist intellectual Rosa Luxemburg, tortured, rifle-butted and shot in the back of the head before her body was dumped in Berlin’s Landwehr Canal; and the former vice-chancellor and finance minister Matthias Erzberger, murdered during a family holiday.

But the book also highlights the creative energy of this intensely disturbed society, with insights into the avant-garde art and architecture of the Bauhaus movement and the attempts by playwrights such as Bertolt Brecht to create ‘a new theatrical experience that was entertaining and thought-provoking at the same time’. There is also a detailed retelling of the silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, now regarded as cinema’s first cult classic and often taken to be representative of the traumatic legacy of the first world war.

The Weimar Years is a timely book, delivering a stark reminder of what happens when democratic foundations become eroded by social division and political apathy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in