This may come to be remembered as the year where the global warming debate became serious. Until now, there has been a shrill quality to the discussion with emotive language used in place of reason. Yes, there’s a serious problem facing the planet – but to what extent would the proposed solutions address this problem? What are the trade offs involved? How does decarbonisation rub up against other obligations, like alleviating cost-of-living pressures and protecting the elderly from the cold?

Deadlines that once seemed far away – like the 2030 ban on new petrol cars – are now getting rather close and focusing minds. The public certainly are concerned about the environment, as evidenced by consumer choices and behaviours, but they are unwilling to be taken for fools.

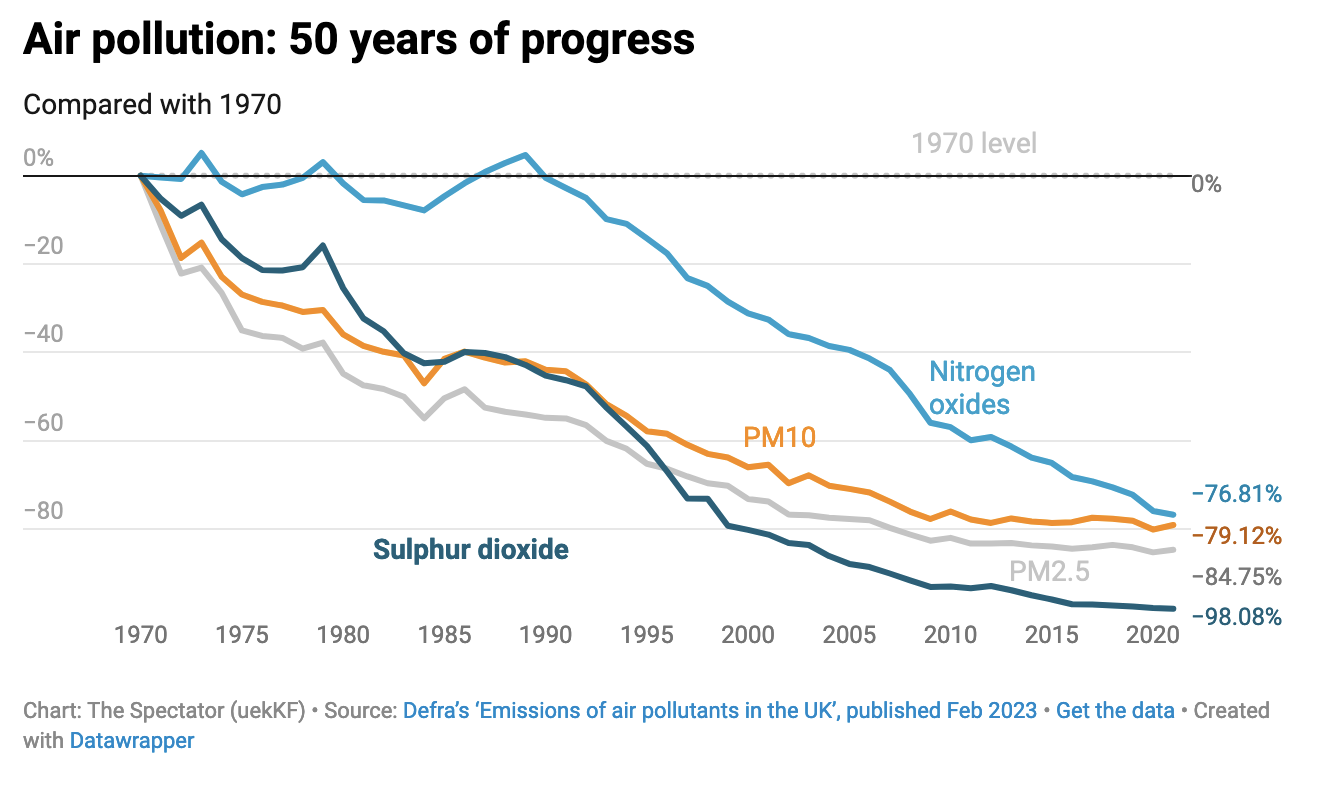

So when Sadiq Khan talks about ‘the air quality crisis’, people may ask: is this the same country where nitrogen oxide levels have fallen by 77 per cent, PM10 by 79 per cent, PM2.5 by 85 per cent and sulphur dioxide by 98 per cent – all in the Mayor’s lifetime? Has London’s air quality ever been better than it is now?

More can be done, to be sure. But it’s far from clear that what we need is more tax on drivers in the doughnut of Greater London, where cars are crucial and public transport weak. This is not just making environmentally-minded voters baulk. Even Keir Starmer is working out the trend: green radicalism is falling away and a new green realism is slowly taking its place.

Polls have been saying as much for a long time: while there is general public support for net zero targets and other green measures, that support rapidly dies away when people are asked about the trade offs currently proposed. Plans to phase out gas boilers are unpopular, as are low traffic neighbourhoods – when, that is, the implications to them are made clear in the question. In Germany, the government nearly fell apart over plans to ban new gas boilers; in the Netherlands, an upstart party formed to oppose plans to close down farms to reach nitrogen reduction targets now stands on the brink of power.

The Uxbridge by-election result has caused ructions not just in the Labour party but among Conservatives too. Michael Gove, who was the minister responsible for the ban on petrol and diesel cars, said this week that net zero must not become a ‘religious crusade’. He has suggested that the plan to ban new gas boilers may also be dropped.

The Prime Minister, too, has reacted to the Uxbridge result by stating this week that the government will pursue its net zero goal ‘in a proportionate and pragmatic way that does not unnecessarily give people more hassle and more cost in their lives’. This has the makings of a new green centre ground.

In making net zero a legally-binding target, Theresa May believed she was getting ahead of a trend. In fact, no other country has joined her in such a rash, unfunded promise, mindful that it’s pointless and dishonest to pledge to do something without having the first idea how you might do it.

There’s a serious problem facing the planet, but to what extent would the proposed solutions address this problem?

There is no sadder sight than a Conservative trying to be fashionable, as Mrs May often demonstrated. Times have moved on. The question is whether Sunak or Starmer will be the first to claim the territory of green realism.

Starmer has beaten quite a retreat so far. He has quaranted Ed Miliband, who is now regarded by Labour as a useful tool to fend off the Greens in seats like Brighton, but someone not to be let near serious policy. Starmer is also opposing Khan’s Ulez low emission zone expansion. He appreciates that the ‘red wall’ seats will not come back to a Labour party that looks ready to tax the working class out of the sky and off the roads. Having de-risked the Labour Party, to the point where it is not really feared, he must now assure voters that Labour would not make them worse off.

Sunak, who has always regarded the net zero agenda as uncosted madness, is in a harder position. The Tories have made more promises: such as the obviously-doomed plan to ban sales of new petrol cars. The cost of green alternatives is not falling fast enough. Heat pumps are decades-old technology whose prices are not tumbling in the way that solar and wind prices have done.

We are living in an age of incredible environmental achievement. Things are good and getting better. Studies suggest UK carbon emissions are at their lowest since Victorian times and London’s air quality is purer now than under the Stuarts four hundred years ago. The average household now uses almost a third less energy than it did even 20 years ago. Energy from renewables will soon overtake that from fossil fuels.

We are learning to tread more lightly on the planet – thanks mainly to the forces of technology, innovation and consumer choice. This is driven by a desire of millions of people to lead a cleaner, greener lives.

But as we see all over Europe, these same people are unwilling to believe the more hyperbolic claims of politicians and pay large taxes for pointless schemes. The Tories may not yet be willing to drop May’s commitment to reach net zero by 2050. But any party which wants to win the next election is going to have to convince the public that green policies are not going to condemn them to a poorer future – and be prepared to relax cherished green policies where necessary.

This is where both Labour and the Tories will end up. The question is which party will realise it first.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in