Many of the best literary children – think the creations of Henry James or Elizabeth Bowen – have something creepy about them. These are girls and boys who see through the hypocrisy of adults, and there’s going to be something unnerving about their precocity. Jean Stafford’s Mollie and Ralph took their place in a lineage with James’s Flora and Miles and Bowen’s Henrietta and Leopold when she flung them, bespectacled and prone to nosebleeds, into the world in 1946.

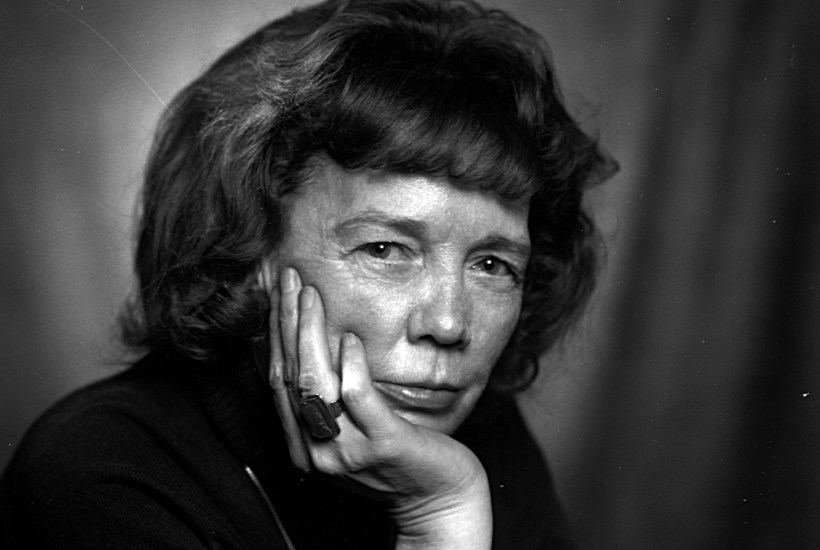

Stafford was the first wife of Robert Lowell, and it’s the main thing most people know about her now – unsurprisingly. Lowell was a man who made his mark on his wives, and in Stafford’s case the marks were literal – he drunkenly drove her into a brick wall. She became a novelist in his orbit and her often violently embattled books emerged from her pugnacious, volatile marriage and the end of the second world war.

Her first novel, Boston Adventure, sold a staggering 380,000 copies when it was published in 1944. The Mountain Lion appeared two years later, and took Stafford back to the landscapes of her childhood in California and Colorado. When the book opens, Ralph and Mollie have just been sent home from school. Since contracting scarlet fever, aged eight and ten, they’ve had a propensity for nosebleeds. They tend to get these at the same time, in their different classes, and are dismissed from school together, telling jokes that they then compete to claim ownership of, and bleeding over the dusty, sinisterly idyllic neighbourhood that Stafford describes so pungently. (There’s a grapefruit tree that bears one grapefruit every year, smaller than a golf ball and almost as hard.)

The plot gets going with the annual visit from their step-grandfather, who conveniently dies the next day, precipitating a division in the family when his youngest son, Uncle Claude, arrives for the funeral and invites Mollie and Ralph to spend the first of many summers in Colorado. There, Ralph attempts to keep up with his uncle’s horse-buckling machismo (his spectacles are abandoned, leaving him with migraines), while Mollie shuts herself in her room, writing, taking refuge in becoming even more of an outsider. Back in California, their mother and elder sisters grow more ludicrously frivolous in their femininity and end up taking a trip around the world, leaving the pair discarded in Colorado.

Sex undoes them – a slow awakening that they squirm their way into, alongside each other and apart, with Mollie feeling a ‘brilliant hatred’ for her brother that ‘had spread over her exactly like bathwater’. Stafford’s gift in this book is her ability to write from the perspective of the children. Even the raw brilliance of her descriptions of the landscapes feel authentically from their point of view. These are children whose absence of feeling is as striking and moving for us as their feelings – they have not been sufficiently loved to know they love.

In the middle of it all is a mountain lion, glimpsed in her ‘wasteless grace’ in the sun and then streaking away across the flat land, leaving Mollie envious of her yellow hair and Ralph and Claude determined to kill her. Once the lion takes over, the book gets less convincing; it loses its luridly incandescent realism and becomes mythical in a way that Stafford doesn’t succeed in making all that interesting. But Mollie and Ralph remain gifts to the world in their watchful awkwardness, their humour and especially in Mollie’s darkly mischievous preparedness to set the adults around her right.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in