Earlier this month, a Chinese spy reportedly tried to enter a private House of Commons meeting with Hong Kong dissidents. The alleged spy claimed to be a lost tourist, and there was a brief stand-off before he quickly left. The area was far from those usually visited by tourists, and some Hongkongers, fearing for their safety, covered their faces during the event.

‘I believe this man was a [Chinese Communist party] informer,’ said Finn Lau, one of two pro-democracy activists at the meeting who have CCP bounties on their heads. ‘This is one of the remotest committee rooms in parliament. And it is on the top floor. It is not a coincidence that a random Chinese tourist was outside the room at the exact right time and was attempting to access the event.’

If the man was a spy, his actions were almost insultingly brazen. However, that should come as no surprise after last week’s scathing condemnation of the government’s China strategy by parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee, which struggled to identify anything that might be remotely described as a coherent policy. The committee said China is engaged in a ‘whole of state’ assault on the UK and concluded that the government had been asleep at the wheel while Chinese spies ‘prolifically and aggressively’ penetrated every sector of the economy. ‘Confusion and obfuscation prevails in Whitehall,’ said the former Tory leader Iain Dun-can Smith when the committee’s findings came out. ‘It is as damning a report on British foreign policy failure as I can remember.’

The government’s muddled and ineffective approach to China is a gift to Keir Starmer’s Labour. And the cannier members on the opposition’s front benches have realised that Labour has been presented with a giant policy vacuum it can fill.

On Monday, in a speech to the Royal United Services Institute, Britain’s leading defence and security thinktank, Yvette Cooper did her best to casually steal Tory clothes on national security. ‘We can’t just sort of drift,’ the shadow home secretary said of the government’s China strategy. ‘It is so serious to our national security, not just today, but for many years into the future… the government is failing to get ahead of the economic risks to our domestic security, which has meant that our response to a fast-changing security landscape has often been disjointed, disorganised and delayed.’

Labour, Cooper said, would counter with an ‘all of state’ defence, with close cooperation between the Treasury and the Home and Foreign Offices to build technological and economic resilience to Chinese interference. ‘We’ve been too slow to identify where risks lie, and how and where to safeguard national infrastructure,’ she said.

It wasn’t long ago that Labour and national security could barely be uttered in the same sentence. After all, this was the party of ‘Beijing Barry’ Gardiner, whose office received £500,000 in donations from an alleged CCP ‘agent of influence’ and employed the agent’s son. Gardiner was a shadow minister on the opposition front bench under Jeremy Corbyn, a man for whom foreign despots could almost do no wrong as long as they shared his crude anti-Americanism.

Cooper is perhaps over-eager to compensate for the Corbyn years, and there’s certainly an element of opportunism and the luxury of opposition to her pronouncements. But Labour is starting to sound tougher on China than the Tories, and the shadow cabinet appears to have grasped the scale and extent of the threat from the CCP more fully than their floundering government counterparts.

Shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves calls her approach ‘securonomics’. In a speech in Washington DC in May, she said that the war in Ukraine and the struggle to obtain PPE during the Covid-19 pandemic had exposed the vulnerabilities of supply chains that ‘prioritise only what is cheapest and fastest’. She warned that the globalised system can be ‘gamed by countries like China who have undercut and ignored the international trading rules’ and, in the process, ‘we have allowed the production of critical technologies to slip from our grasp – costing us jobs and compromising our security’. It is easy to dismiss her approach as part of a broader agenda of greater protectionism and state intervention in the economy, but on China she aligned Labour closely with Joe Biden’s administration which, like Donald Trump’s before it, has tried to reduce America’s reliance on cheap Chinese industry.

Reeves endorses what has become known as ‘friend-shoring’, the shifting of critical supply chains to more pro-West countries. ‘Nations who share values and concerns, and who want to seize the opportunities of tomorrow, can and must work together to boost our collective resilience and security,’ she said.

Shadow foreign secretary David Lammy has also taken a strong stance on China, especially on issues of human rights. Earlier this year, he said that if Labour formed the next government he would ‘act multilaterally with our partners’ to seek recognition of China’s actions in Xinjiang as genocide through the international courts. Two years ago, Labour backed a Commons motion accusing China of genocide against the Uyghur Muslims, more than a million of whom have been detained in ‘re-education camps’ where there have been well-documented allegations of torture, slave labour, forced sterilisation and sexual abuse. The government has resisted using the term ‘genocide’.

When a Hong Kong pro-democracy protestor was last year dragged into China’s general consulate in Manchester and beaten by CCP officials, including China’s consul-general in the city, the government’s response was described as a ‘complete mess’ by Catherine West, Labour’s shadow foreign minister for Asia and the Pacific. She joined Tory backbenchers in calling for action. Instead, the government dithered for two months until China, which had refused to hand over CCTV footage and waive diplomatic immunity, voluntarily withdrew six diplomats.

When the Hong Kong government this month placed a bounty of one million Hong Kong dollars (around £100,000) on each of eight pro-democracy activists – three of whom now live in the UK – West demanded that sanctions be placed on leading members of the Hong Kong government. ‘Will the government grow a backbone and live up to our moral and legal obligations to Hongkongers both here in the UK and in Hong Kong?’ she asked. The Foreign Office minister Anne-Marie Trevelyan ducked the question, reiterating how generous the UK has been to the 160,000 settlers from Hong Kong who have arrived since the CCP crushed the ‘one country, two systems’ arrangement under its authoritarian National Security Law in 2020.

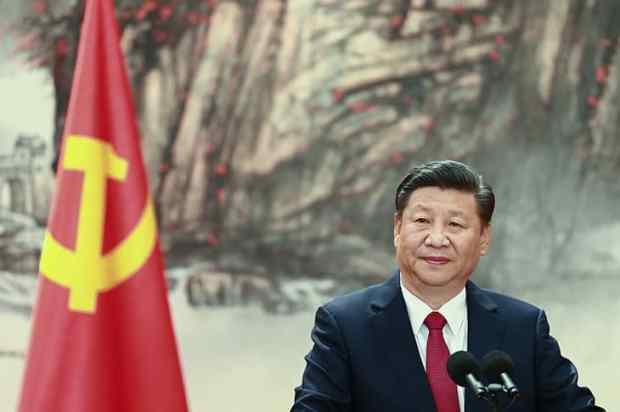

The government appeared to have different priorities. Two months ago, investment minister Dominic Johnson was despatched to Hong Kong to trawl for cash. He was the first UK minister to visit Hong Kong since the CCP crackdown and his trip dismayed pro-democracy activists. Last month Trevelyan was photographed smiling alongside Liu Jianchao, the visiting head of the CCP’s international liaison department. Liu is one of the more thuggish of Xi Jinping’s henchmen. He has been described as China’s chief dissident-catcher, in charge of party operations targeting critics across the world. Asked about the meeting, Trevelyan said: ‘We consider it important to engage with our Chinese counterparts, where appropriate, to protect UK interests and to build those relationships.’

Last week’s Intelligence and Security Committee report should be seen as the culmination of a series of increasingly strident public warnings by the heads of the UK’s intelligence agencies, MI5, MI6 and GCHQ, about the breadth and scale of Chinese espionage and influence operations. It should worry Conservative election strategists that Labour now appears closer to the position of the agencies than the traditional party of national security does. And it is not lost on Tory backbench critics of the government’s China policy that their own position is closer to that of Labour’s.

Rishi Sunak has tried to brush away the report’s findings by claiming they were mostly historic and that his government is now more robust on China. There are certainly more tools in place, such as the ability to vet investments and to advise academia on national security. The government intervened in eight attempted takeovers of UK firms by Chinese buyers last year. However, the process has been criticised as opaque and lacks any independent oversight.

Sunak describes his approach to China as ‘robust pragmatism’, while Foreign Secretary James Cleverly, who is expected to visit Beijing soon, says he wants a more constructive but robust relationship – whatever that means. It is hard not to conclude that the Tory strategy is not to have a strategy, to fumble along in pursuit of Chinese money, while sending out confused and contradictory signals, avoiding any serious offence to Beijing. It is all starting to sound a lot like a retread of the disastrous Cameron-Osborne years. And while Labour’s policy is far from fully formed, at least on the opposition benches there is emerging something that can be described as a strategy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in