The upheavals convulsing the Russian empire in 1917, Victor Sebestyen argues convincingly, were the seminal happenings of the past century. From them directly stemmed the second world war, the Cold War, the collapse of European imperialism and the dangerous world we inhabit today. There are many weighty modern accounts of these epochal events by historians such as Richard Pipes, Robert Service and Orlando Figes, and it is these that Sebestyen chiefly relies on in this brisk, well-informed and chilling account. He makes no pretence of original research.

‘The Russian Revolution’ is something of a misnomer as, strictly speaking, there were two such eruptions in 1917: a genuine, spontaneous revolution in February, and the planned coup d’etat by the Bolsheviks in October that founded the Soviet state. The motives of this tightly knit group of men were laudable, even idyllic. In the words of Trotsky, one of the main movers:

I can see bright green strips of grass, clear blue sky and sunlight everywhere. Life is beautiful. Let future generations of people cleanse it of all evil, oppression and violence and enjoy it to the full.

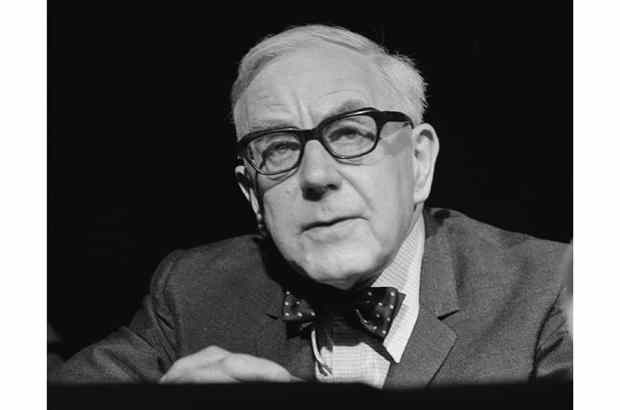

So what went wrong? How did this childlike vision become a nightmare system, itself dependent on evil, oppression and violence? A system in which Trotsky, for all his later protestations of innocence, was mired in blood. Challenging Marx’s dictum that impersonal factors rather than individuals are the moving forces of history, Sebestyen focuses on one man as primarily guilty of both making and perverting the revolution – Vladimir Ulyanov, otherwise known as Lenin, the fanatical polemicist who returned from Swiss exile, bullied his more timid comrades into seizing power and then insisted that the new society he was creating had to be more cruel, rapacious and murderous than its enemies to survive.

Sebestyen describes Lenin as a clean-living ascetic who never personally killed anyone and was no sadist. But he then weakens his argument by liberally quoting the dictator’s orders to his subordinates: ‘Let there be blood’, ‘Shoot them’ and ‘Death to all of them’. Lenin may not have been a sadist exactly, but he was certainly a vicious psychopath, and the society he constructed was built on the bones of his victims.

It was Lenin, not Stalin, who founded the Cheka (the secret police), who first extorted grain from starving peasants and insisted that revolutions could only be made by firing squads. The machinery of repression and mass murder was in place by the time he died in 1924. All Stalin had to do was use it.

Sebestyen’s early pages provide ample evidence of why revolution was inevitable. He paints a vivid picture of a vast country stuck in backward feudalism, despite the ‘liberation’ from serfdom of 85 per cent of the population in the mid-19th century. The Romanovs oscillated between savage reaction and inadequate reform, and were seemingly unworried that an astonishing 20,000 of their officials were assassinated during the last 25 years of their reign. Tsardom survived one revolution in 1905, triggered by Russia’s war with Japan, but a greater war with Germany in 1914 spelt doom for the ancien régime. By the time that bread riots sparked revolution in the freezing winter of 1917, Russia’s armies were deserting, and even conservatives were plotting revolt.

The first leader thrown up by the revolution, Alexander Kerensky, was a well-meaning drama queen who made the double mistake of continuing a hopeless war with a mutinous army and not shooting Lenin when the Bolshevik leader returned with the seductive slogan: ‘Peace, Land and Bread.’ Lenin didn’t mean it, of course. His goal was always a one-party dictatorship run by those who thought like him and treated the real workers with contempt. The ‘former people’ classes who once ran Russia were condemned to exile or extinction, while the rest began their 74-year jail sentences.

Reading this chronicle raises melancholy reflections about the present condition of Russia under its wannabe Lenin. A century after the original’s death, another bad Vlad is replicating his predecessor’s ugly example. Russia deserves better than rulers addicted to grandiose dreams of perfection but actually dedicated to bringing only suffering and death.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in