Australians have been told that if we want to understand the Voice proposal we should read the 272-page Final Report to the Australian Government ‘Indigenous Voice Co-design Process’. Having undertaken that task, it is possible to clarify several key design features of the Voice. This assessment focuses on how the 24 National Voice members will be selected.

What remains open to question is whether each Australian Indigenous person will have a genuine and democratic input into the selection process. Alternatively, will the process be a pretence of democracy enabling powerful individuals, factions, clans, and so on within Indigenous communities to control the selection process for their own benefit? The answer at this stage is that there is no answer… We simply do not know.

The structure of the Voice is as follows:

Australia is to be divided into 35 local and regional Voice districts. How those districts are to be constituted, what geographic areas they will cover, who will be in them, how they will be structured, which people will be spokespersons for each Voice district, and how those persons will be selected is not stipulated in this report. Instead, those questions will only be answered once the Voice is established. The only guidance on this offered by the report is general in nature.

The report says:

‘Consideration of detailed boundaries will be based primarily on cultural groupings and existing regions. Regions will generally align with state/territory boundaries but cross-border arrangements will be considered…’ (page 24)

And:

‘The design of the Local and Regional Voices should reflect the varying practices of different Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities…’ (page 8)

That is, once the Voice is established, each one of Australia’s 35 (yet undetermined) Voice districts will go through a process of deciding how their Voice will be structured and populated.

Each district process can be, and presumably will be, different and what their Voice institution will look like and who will control it will be different. The report goes on to say, ‘Each Local and Regional Voice will be different but all will be community-designed and led. Broadly, each is expected to include: a leadership group at the regional level…’ (page 24)

There will be no consistency about what standards of behaviour for local Voice members would be. The report adds, ‘Guidance will be developed regarding expectations of members and what should be covered by a code of conduct for Local and Regional Voices. Each region would tailor this to its circumstances.’ (page 62)

There is one exception to this general lack of detailed specifics – namely, a stipulation for equal gender representation.

Whatever the outcome of this process, relevant Commonwealth and state/territory legislation would formalise the structures.

Sitting above the 35 Voice districts will be the National Voice structure.

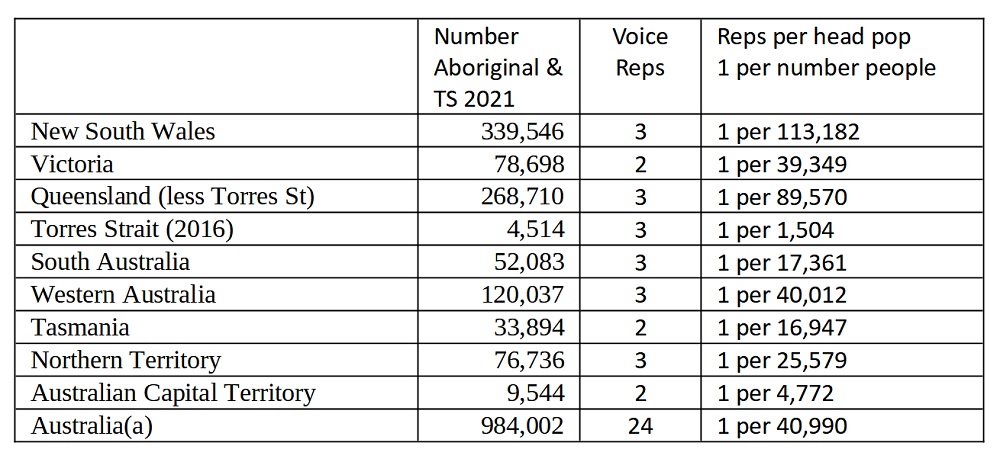

The National Voice will have 24 members allocated on a state, territory and Torres Strait Islander basis (page 18) as shown in the table below. Featured are the numbers of Indigenous people in each state and territory and the number of Indigenous people represented by each state or territory’s Voice member.

(The population figures are from the ABS sources listed below the Table.)

ABS 2021. Number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders

ABS 2016 Number of Torres Strait Islanders in Torres Strait

The first observation to make is the major numerical (and hence power) imbalance between the states/territories. New South Wales is the most disadvantaged, followed by Queensland and Western Australia. The Torres Strait Islanders, Canberra (ACT), Tasmania, South Australia, and Northern Territory will have dominant sway with 13 of the 24 representatives. That is, these smaller states/territories with just 18 per cent of the Indigenous population will have more than 50 per cent of the representatives on the Voice.

How the National Voice representatives are to be selected is not detailed. Instead, as with the selection of the 35 District Voice representatives, the selection process is yet to be determined.

The report offers three alternative selection options, with the default option being ‘Local and Regional Voices collectively determine the National Voice members for their state territory and the Torres Strait.’ (pages 18 & 112)

The role of Torres Strait peoples is complicated by the fact that large numbers of Torres Strait Islanders live on the mainland. (pages 123 & 125) The report discusses this but does not resolve the role these non-resident Torres Strait Islanders will have in the Voice members selection process other than saying they should have a role.

These first observations make it quite obvious that the Voice members selection process – at either level – is profoundly undemocratic for the Indigenous peoples themselves. There is no suggestion in the report that Indigenous people will have an entitlement to vote directly for their Voice representatives. Indeed, what discussions there are about election of representatives (described as ‘Core Model 2’ in the report) seem to go out of their way to raise objections to the use of elections. (pages 112 to 114)

And even if there were a vote requirement, the Voice structure at the National Voice level entrenches the worst of ‘gerrymanders’ as the Table above shows. There is nothing in the report that explains why there should be such marked differences in effective representation across and between States and Territories.

Other key features of the National Voice structure as explained in the report are that, once selected, the 24 Voice members can appoint two additional Voice members, making a total of 26 Voice members (pages 108 & 132). There must be equal gender representation on the Voice. (pages 108 & 126). Terms are for four years on a two-year rotation basis. (pages 108 & 134)

Once established, the Voice members will appoint an ethics committee that will define and determine, amongst several matters, what constitutes a ‘fit and proper person’ for eligibility to be a Voice member, including ‘considering matters of misconduct and eligibility of National Voice members’. (pages 136 to 138)

Persons eligible to be a Voice member must be over 18 years old, be Indigenous, not be a bankrupt, pass a ‘fit and proper person’ test, and are eligible if in prison for less than 12 months. (pages 139 to 141)

Further, the National Voice members will be part-time, paid for meeting attendance and preparation and expenses, but otherwise not paid. However, there will be two co-chairs (one female and one male) who will be full-time and paid, and form the leadership of the National Voice. There would be an Office of the National Voice with a CEO supporting the Voice members. (pages 133 & 181)

The National Voice and the 35 Voice Districts are to operate as an intertwined whole with links to and from the National and District Voices. (pages 145 & 156)

Further, there are to be two permanent advisory groups, one for youth and the other for people with disability. (page 173)

From this understanding of the Voice structure several observations can be made.

First, how genuinely representative of all Indigenous people in Australia the Voice will be is unknown. Whether individual Indigenous people will exercise a form of direct one-person-one-vote participation is not known and will not be known until after the Voice is created. Certainly, discussions and explanations in the Final Report would suggest that a direct vote-style selection process is not a favoured option.

Second, the Final Report indicates that the Voice structure would create an immense concentration of power in the hands of a few Indigenous people.

This concentration of power is assured in the first instance because Voice membership is heavily skewed toward the less Indigenous-populated states and territories. To attain power in the National Voice an astute and wily player need only concentrate on those smaller states and territories which, with 18 per cent of the Indigenous population, can deliver majority control of the Voice institution.

Further the structure of the National Voice itself, with its 24 (or 26) members, will place enormous, perhaps dominant, power in the hands of the two co-chairs (one female and one male).

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the Voice proposal is not a proposal to actually create something as such in terms of the representative selection process. The Voice proposal is a proposal (a) to create a process that will (b) create a process by which the Voice representatives will be selected. What that selection process will be is entirely unknown.

This understanding of the Final Report leaves open the question. Will the Voice be a genuine voice for all of Australia’s Indigenous people or will it be a tool for the concentration of power in the hands of particular individuals and factions within Indigenous communities? There is no answer.

Ken Phillips is Executive Director of Self Employed Australia and is on Substack

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in