What should we make of present-day Belfast and its compelling, fractious backstory? English visitors have long found the city invigorating, confusing or exasperating – often all three – but undeniably characterful. Philip Larkin, who lived there for five years in the 1950s, noted its ‘draughty streets, end-on to hills, the faint/Archaic smell of dockland’ and found himself enjoying the ambiance: ‘the salt rebuff of speech/ insisting so on difference, made me welcome’. Not so Sir Reginald Maudling, on his first visit as home secretary amid the escalating sectarian insanity of 1970. He boarded the plane back to London with the words: ‘For God’s sake, bring me a large Scotch. What a bloody awful country!’

Those who grew up there, as I did, have a tendency to absorb its history more by inhalation than education, leaving gaps in the detail. To read Feargal Cochrane’s wide-ranging account of the city, therefore, is to ricochet pleasurably between recognition and surprise. I knew, for example, that the name Belfast derives from the Irish words Béal Feirste, but not that Feirste refers directly to the river Farset, a dwindled tributary of the river Lagan now trapped and hidden underground: ‘The main artery of the Farset still flows up High Street today, contained within large pipes under the road, some of which are so big you could drive a bus through them.’

The reminder of this subterranean force seems fitting for a place with its own fluid seam of metaphorical darkness: the sectarian tensions that have sporadically burst forth in streets or shipyards to engulf its citizenry. Their origins go back to the man widely regarded as Belfast’s founding father, a wily Elizabethan brute called Sir Arthur Chichester, who built up the city as a bastion of English control while pursuing a scorched- earth policy with regard to the native Catholic Irish. Early 17th-century Protestant plantations from the north of England and the Scottish lowlands complicated identities and allegiances.

Some historical alliances may surprise students of the political landscape today, as in the late 18th century when Belfast Presbyterian merchants such as Henry Joy McCracken – part of a radical, dissenting culture fired by the French revolution – made common cause with the Catholic Irish to challenge the Anglican Protestant ascendancy and British rule. But their United Irishmen’s 1798 rebellion went chaotically wrong, and wavering Presbyterians shifted back to loyalty to the Crown.

The Troubles grew out of a different context: a post-partition Ireland in which Belfast was the capital of a predominantly Protestant, unionist state, partly defined by its difference to the explicitly Catholic, nationalist Republic of Ireland. As a result, many northern Catholics felt marginalised and resentful within it. Yet even as Belfast erupted into sectarian mayhem – with a speed that shocked the majority of its residents – the lunacy was unevenly distributed throughout the city. The author, himself a Catholic, describes a ‘wonderfully happy childhood’ in a mainly Protestant east Belfast street which included some Catholic families. But as he got older, like most Belfast children of that era, he also acquired an instinctive wariness in territories where a name or school uniform might disastrously betray one’s status on ‘the other side’.

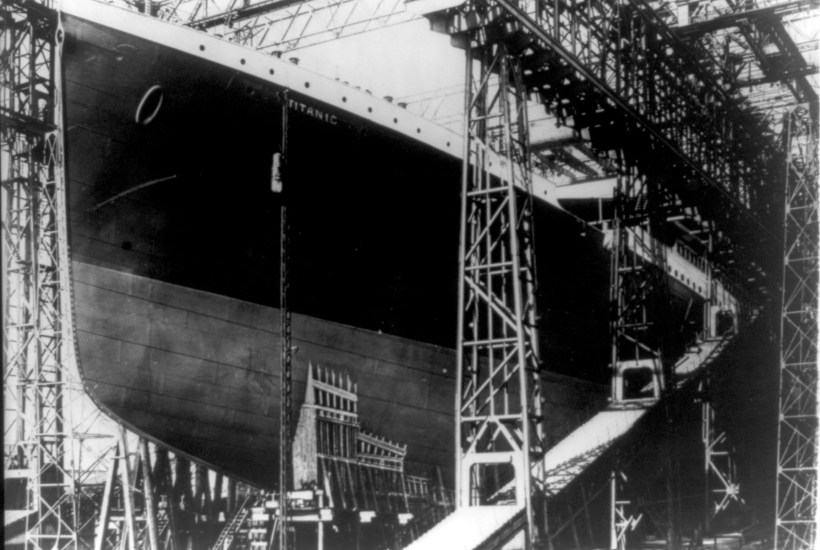

Before the Troubles hijacked the name of Belfast worldwide, however, it was known for its great industries – linen and shipbuilding – which pulled in its working classes from ‘beleaguered rural communities’ and often devoured them in industrial accidents or disease. In early 20th-century Belfast, before Ireland’s 1921 partition, my great-grandfather died after a ship’s bell he was engraving dropped on his foot, triggering a fatal infection. Another set of great-grandparents perished from tuberculosis, and my paternal grandmother began work in the mill as a ‘half-timer’ aged 12, alternating schooldays with 12-hour days spent ‘wet spinning’ in bare feet. It’s fascinating here to absorb the context around these dramatic, precarious lives, but also the sheer scale of their productivity. By 1914, Belfast’s ‘Wee Yard’ and the Harland & Wolff shipyards alone were ‘responsible for an eighth of the global shipbuilding trade’.

It was Harland & Wolff that built the Titanic, of course, now commemorated in the Belfast Titanic museum, the city’s top tourist attraction. To outsiders it might seem odd that Belfast should take such pride in constructing one of the world’s best-known disasters, but it chimes with a flamboyantly melancholic streak in the city’s psyche. Belfast City airport is named after the footballer George Best, whose spectacular early talent was also scuppered by a dramatic collision, in his case with alcohol.

A portrait emerges from these pages of a city alive with contradictions: roaring sectarian preachers and lyrical poets; building and wrecking; friendliness and murder; an obsession with history and shameful neglect of it (the 18th-century Assembly Rooms, in which Henry Joy McCracken was tried for treason, have been ‘left to rot unloved’, along with many other decaying period properties in once celebrated areas).

As to the city’s future, Cochrane is confident that despite ‘significant’ divisions and challenges ‘it has surely never been better placed to face them over the past 100 years than it is today’. I find myself more worried. The author sees hope in the newly cordial relations between Sinn Fein and the British royal family, but what of the deteriorating ones with their Protestant, unionist neighbours? The combination of a paralysed power-sharing government, an increasingly isolated, defensive Unionism and an electorally buoyant Sinn Fein – now arguing there was ‘no alternative’ to past IRA violence – seems dangerous in a historically volatile city still criss-crossed by ‘peace walls’.

I hope I’m wrong. For residents and émigrés alike, Belfast gets under the skin and maddens it. The author, an academic who lives in England but often returns to his home city, describes this book as ‘a love letter of sorts – but written from the point of view of someone who is repeatedly vexed by the relationship’. I know the feeling.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in