The Coutts scandal can be traced back to the day, two years ago, when the bank proudly announced that it had achieved ‘B Corp’ status. B Corp is a little-known non-profit which operates a scheme a bit like Stonewall’s Diversity Champions Programme. Companies that sign up and jump through the necessary hoops will receive a certificate declaring that they’re ethical and inclusive.

B Corp’s website declares: ‘Certified B Corporations are leaders in the global movement for an inclusive, equitable and regenerative economy.’ It adds that its scheme seeks to measure ‘a company’s entire social and environmental impact’.

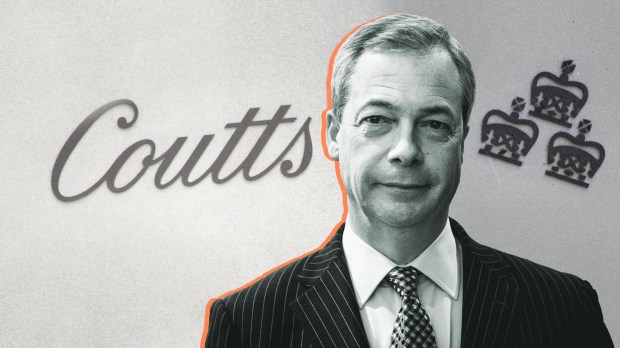

When Coutts announced itself a B Corp, it was essentially saying that the bank had been politicised, which should have been a warning of what was to follow. Nigel Farage was excluded from the bank as part of its inclusivity agenda. His politics did not align with the bank’s values, so he was punished and ‘debanked’.

A bank should be concerned with finances, not politics. NatWest’s attack on Farage was a political hit-job, but the board of NatWest, which owns Coutts, seem to have thought their actions were reasonable. Their main regret seems to be not that all this happened, but that it became public.

Before she had to resign as chief executive, the NatWest board was declaring ‘full confidence’ in Dame Alison Rose. Once, it would have been a sackable offence for a junior in a bank to break client confidentiality. Yet when the chief executive herself admitted to doing so – in talking to a journalist about Farage’s finances – she thought, even briefly, that she could carry on. Old-fashioned banking values seemed to have been forgotten.

This is not a row about Farage. It is a shocking exposé of the culture that has prevailed in Coutts and NatWest. The banks sought to exercise political power and abandoned their duty to their clients. This mentality, sometimes described as ‘woke capitalism’, is alarmingly widespread. It typically sets in when the HR departments of large corporations believe they have to enforce ‘environmental, social and governance’ issues. This quickly morphs into a political agenda and declarations of corporate ‘values’.

Rather than promoting diversity, it ends up imposing political homogeneity. We see, for example, companies asking employees to celebrate a Pride month that many think reinforces damaging stereotypes. Or Black History Month, which many black Britons believe foists a narrative on them on the basis of their skin colour. On a wider level, woke capitalism can mean that employees are judged, promoted or even penalised for holding or dissenting from certain views.

The Bloomberg writer Adrian Wooldridge pointed out in a cover story for this magazine in April how these tactics are eroding meritocracy. Employees are being judged on their backgrounds or their espousal of political opinions rather than the ability to do a job. At Coutts, this ideology mutated to the point where the bank was compiling 40-page documents on the political views of one of its clients and listing baseless slanders against him. Until Farage himself exposed this, no one at the bank seems to have considered such a dossier unusual, let alone outrageous.

Business and politics should be kept separate, yet woke capitalism wants to fuse them. ‘Partnership between government and business is the cornerstone of a sustainable growth economy,’ proclaimed Rose earlier this month as she was inaugurated as a member of Rishi Sunak’s business advice board. This is quite wrong. Government should create a level playing field and see that basic regulation is enforced – and then get out of the way.

One big difference in Rose’s case is that NatWest is part owned by the taxpayer – a legacy of the 2008 banking bailouts. This meeting of banking and politics has had inevitable and far-reaching consequences. The UK government ended up taking an 84 per cent stake in NatWest at the height of the financial crash and has been reducing this slowly – it is currently at 39 per cent. The main job of any NatWest chief executive should be to ensure that its shares rise in value and that the taxpayer is eventually reimbursed. There seems no hope of that. Years of missed opportunities have left NatWest’s shares at about half the 500p level of the original bailout.

The drift of large corporations towards a set of values born out of US business schools really matters. Not least because B Corp status encourages companies to change their corporate structures so that they are run not for the interests of their shareholders but for all ‘stakeholders’, which is supposed to include ‘customers, workers, suppliers, communities and the environment’. If this means companies working to undeclared political agendas, it raises several serious issues.

NatWest has emerged from the Farage scandal not as an ethical champion but as an organisation that is willing to abuse its corporate power and use its customers to promote a particular set of political values. We can at least be grateful that we now know how deeply the rot had set in. This is, if nothing else, grounds for a debate about how to protect customers, employees and consumers from a political agenda that has gone unscrutinised and unchallenged for too long.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in