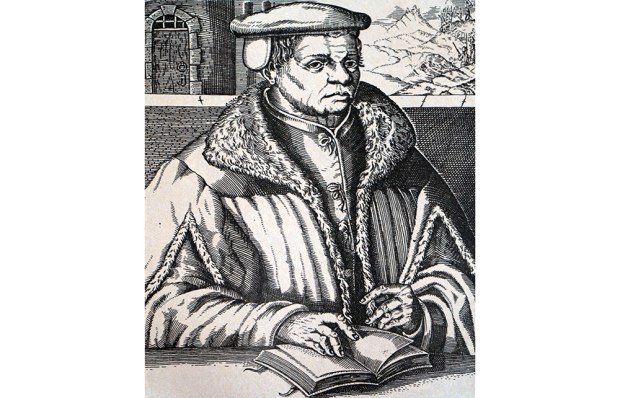

The first woman to put the Spencer family on the map was not Diana, Princess of Wales, the youngest daughter of the 8th Earl Spencer, nor even Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, the elder daughter of the 1st. Rather, it was their Tudor forebear Alice, Countess of Derby, the subject of this absorbing biography by Vanessa Wilkie.

Born at Althorp – then a modest, two-storey red brick manor house – in May 1559, six months into the reign of Elizabeth I, Alice was the youngest daughter of Sir John Spencer, a prosperous sheep farmer and sometime sheriff of Northamptonshire, and his wife Katherine, née Kytson. At the age of about 20, Alice married Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange. It was a brilliant match for her and the Spencers.

Heir to the earldom of Derby, Ferdinando was also a great-great-grandson of Henry VII. (The Spencer family tree, as Wilkie wryly observes, was but ‘a sapling’ by comparison.) Indeed, Ferdinando’s Tudor blood meant that he was a potential successor to the childless Virgin Queen. So, too, were the three girls Alice bore him over the course of the 1580s: Anne, Frances and Elizabeth. As events transpired, however, Ferdinando’s tenure as 5th Earl of Derby lasted less than seven months. He died suddenly in the spring of 1594, aged 35, following a short illness – variously ascribed by contemporaries to witchcraft or poisoning by Catholic plotters. Alice, who was pregnant at the time, miscarried shortly after.

Ferdinando is perhaps best remembered as an important patron of the arts. Lord Strange’s Men, his troupe of actors, was one of the leading late-Elizabethan theatrical companies and may have counted the young Shakespeare among its members. Alice was a noted patron too – and a muse to several poets, including John Milton, who called her a ‘rural Queen’, such as ‘All Arcadia hath not seen’, and Edmund Spenser, who praised her ‘excellent beauty’ and ‘virtuous behaviour’. Despite a difference of spelling, Spenser claimed a (probably fanciful) familial connection, noting that he felt a ‘private band of affinity’ to the Spencers in general and to Alice in particular.

Alice was also, in Wilkie’s memorable phrase, a ‘skilled cultural matchmaker’. When Anne of Denmark, travelling from Edinburgh to London for her coronation, paused en route at Althorp in June 1603, she was entertained with a masque that Alice had commissioned for the occasion from Ben Jonson. The new queen consort was soon commissioning masques of her own on a regular basis from Jonson – and performing in them herself from time to time.

The lives of Tudor women, even those of high status, are not always easy to piece together since their thoughts and experiences were committed to paper less often than those of their male counterparts. Alice’s life, however, can be reconstructed in un-usual detail, in part because she was exceptionally litigious. In 1594 – newly widowed and recovering from a miscarriage – she embarked on a long and expensive legal battle with her late husband’s brother, William, now the 6th Earl of Derby, over the terms and conditions of Ferdinando’s deathbed will.

In 1600 – midway through what proved to be 13 years of litigation – Alice took as her second husband Sir Thomas Egerton, the judge dealing with this dispute. As Wilkie puts it: ‘What better way to ensure a successful outcome than to marry the man at the helm of the equitable courts?’ And so it proved. The 6th Earl of Derby was ‘outplayed at every level’ by his former sister-in-law. Wilkie – the curator of early modern manuscripts at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California – knows her way around the archives, and has a gift for extracting the human drama from what in other hands might seem dry legal proceedings.

A great dynast, Alice – who continued to style herself Countess of Derby even after her second marriage – engineered socially and financially advantageous matches for her daughters. Anne was married off to the 5th Baron Chandos of Sudeley, Frances to the 1st Earl of Bridgewater, and Elizabeth to the 5th Earl of Huntingdon. Like their mother, all three were noted patrons of poets and dramatists – and Elizabeth an author in her own right.

Anne’s second marriage – to Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven – provides a sad coda to the story of Alice’s spectacular rise. In 1631 he was found guilty of ordering a servant to rape his wife and was executed on Tower Hill. Alice died in 1637, at the age of 77, having outlived both her husbands and two of her daughters.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in