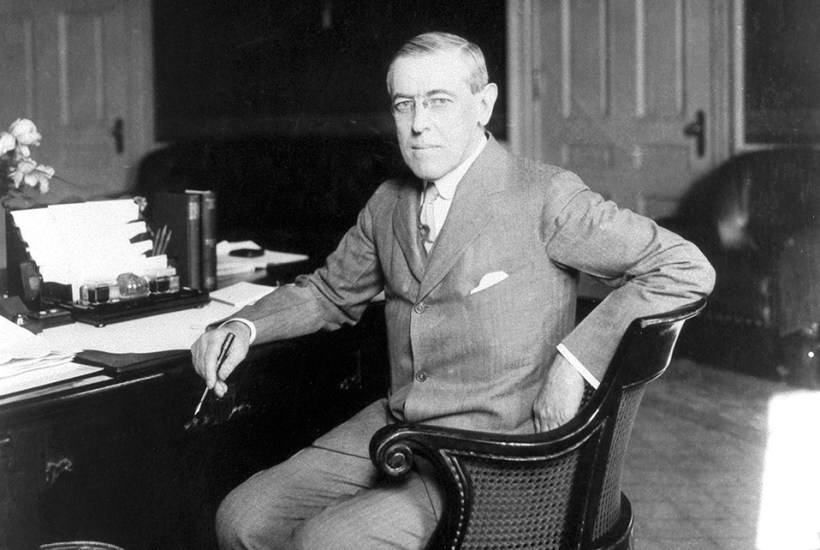

It was a vision that President Woodrow Wilson could not resist. The Treaty of Versailles, and the League of Nations founded during the negotiations, were meant not just to end the first world war but all future wars by ensuring that a country taking up arms against one signatory would be treated as a belligerent by all the others. Wilson took his adviser Edward ‘Colonel’ House’s vision of a new world order and careered off with it.

Against advice, he attended Versailles in person and let none of his staff in with him during the negotiations. He was quickly overwhelmed, saw his principled ‘14 points’ deluged by special provisions and horse-trading, and returned home convinced that his dearest close colleagues had betrayed him (which they hadn’t). He was also sure that the League of Nations alone could mend what the Treaty of Versailles had left broken or made worse (which it didn’t); and that he was the vessel of divine will – that what the world needed from him at this crucial hour was a show of principle and Christ-like sacrifice. ‘The stage is set,’ he declared to a dumbfounded and sceptical Senate; ‘the destiny is disclosed. It has come about by no plan of our conceiving but by the hand of God who has led us into this way. We cannot turn back.’

Winston Churchill had Wilson’s number: ‘Peace and goodwill among all nations abroad, but no truck with the Republican party at home. That was his ticket and that was his ruin and the ruin of much else as well.’ When it was clear that Wilson would not get everything he wanted, he destroyed the bill utterly, needlessly ending US involvement in the League before it had even begun.

Several developments followed ineluctably from this. Another world war, of course; also a small but vibrant cottage industry in books explaining just what Wilson had thought he was playing at. Patrick Weil’s The Madman in the White House captures the anger and confusion of the period. His evenness of manner sets the hysteria of his subjects into high relief. Take, for example, Sigmund Freud, who blamed Wilson for the break up of the Austro-Hungarian empire: ‘As far as a single person can be responsible for the misery of this part of the world, he surely is.’

Anger and a certain literary curiosity drove Freud to collaborate with William C. Bullitt, Wilson’s erstwhile adviser, on a psychobiography of the man. Freud’s daughter Anna hated the final book, but one has to assume she was dealing with her own daddy issues. Delayed by decades so as not to derail Bullitt’s political career, Thomas Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study was published in bowdlerised form, and to no very positive fanfare, in 1967. Bullitt, by then a veteran anti-communist, was chary of handing ammunition to the enemy, and suppressed the book’s most sensational interpretations involving Wilson’s latent homosexuality, his overbearing father and his Christ complex. In 2014, Weil, a political scientist based in Paris, happened upon the original 1932 manuscript.

Are the revelations contained there enough on their own to sustain a new book? Weil is circumspect, enriching his account with a detailed and acute psychological biography of his own – of Freud’s collaborator. Bullitt was a democratic idealist and political insider who found himself pushed into increasingly hawkish postures by his all too clear appreciation of the threat posed by Stalin’s Soviet Union. He made strange bedfellows over the years. On his deathbed he received a friendly note from Richard Nixon: ‘Congratulations, incidentally, on driving the liberal establishment out of their minds with your Wilson.’

In fact John Maynard Keynes’s 1919 book The Economic Consequences of the Peace had chopped up Wilson long before, tracing ‘the disintegration of the president’s moral position and the clouding of his mind’. Then there was the 1922 Wilson psychobiography that Freud did not endorse, though he wrote privately to its author, William Bayard Hale, that his linguistic analysis of Wilson’s prolix pronouncements had ‘a true spirit of psychoanalysis in it’. And Alexander and Juliette George’s Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House, a psychological portrait from 1964, argues that Wilson’s father represented a superego whom Wilson could never satisfy. There are several others if you go looking.

So, is Madman a conscientious but unnecessary book about Wilson, or an insightful but rather oddly proportioned one about Bullitt? The answer is both – and this is not necessarily a drawback. Bullitt’s growing disillusionment with the president, his hurt and, ultimately, his contempt for the man shaped him as surely as a curiously unhappy childhood and formative political debacle at Princeton shaped Wilson.

‘Dictators are easy to read,’ Weil writes. ‘Democratic leaders are more difficult to decipher. However, they can be just as unbalanced as dictators and can play a truly destructive role in our history.’ This is well put, but I think Weil’s portrait of Bullitt demonstrates something broader and more hopeful: that politics – even realpolitik – is best understood as an affair of the heart.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in