The publishers of this handsome volume hint at high adventure – and period adventure at that. In the blot left by an antique quill pen swirls a breaking wave. Ah, the high seas! And here we are again with Aubrey and Maturin picking weevils out of ship’s biscuits and foiling Napoleon’s naval plans.

So I had better warn readers that this isn’t really representative. The first story in the collection, ‘The Return’, is about a man returning to childhood haunts and fishing for trout. The second, ‘The Last Pool’, is different in that this time the fish are salmon (although the protagonist starts out looking for trout). Internal evidence suggests that this is not set in the time of the Napoleonic wars, although, as against the contemplative melancholy of the first story, ‘The Last Pool’ is probably as exciting a tale about angling as you are going to get.

But there are other stories which you would not have guessed were written by someone who liked his swashbucklers. There are unhappy couples (‘Samphire’); highly awkward issues surrounding surrogate parenthood (‘The Handmaiden’); collapsing marriages (‘The Stag at Bay’); the Parisian art world (‘A Journey to Cannes’), and life in an unnamed dictatorship (‘The Overcoat’). And although there is more about fishing, and the high seas in 1800, the 43 adult tales published here are more diverse in subject matter than you might ever have imagined. If they have anything in common it is their competence – which sounds condescending, but isn’t meant to be. (I merely want to suggest: don’t expect anything in the manner of formal innovation or literary avant-gardisme.) The natural world often features, and is closely observed; so are the austerities of 1950s Britain, and the pinched reticence of the people who lived in it.

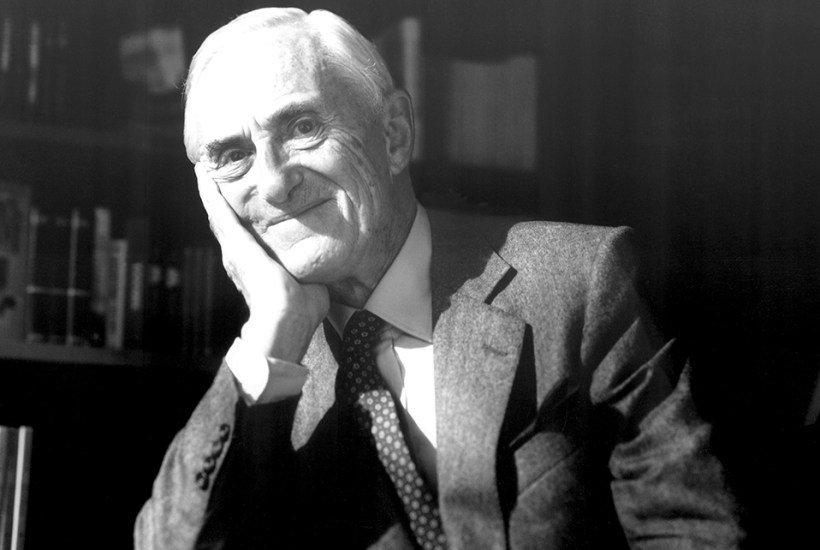

Patrick O’Brian knew what he was doing all right. He had, after all, published his first novel at the age of 15 (Caesar:The Life Story of a Panda Leopard), and these tales – many of them no more than five or six pages long – have a sense of classic perfection. You can imagine them being set for commentary in an A-Level paper or photocopied and handed out by English teachers to their better classes. (‘Here you go: this is how to do it. Note how the weather reflects…’) Every so often there’s a squirt of sharpness. The impoverished hack in ‘The Stag at Bay’, struggling to write an amusing piece about marriage while his own is disintegrating, is a painfully comic figure. ‘In the morning the tide of washing-up reached Edwin’s desk itself’ is one particularly relatable sentence.

But as well as the adult stories there are children’s ones – 20 of them. Now these are quite fascinating, and originally appeared before the war in publications such as The Oxford Annual for Scouts, The Oxford Annual for Boys and Chums Weekly. They are generally about animals, like O’Brian’s first novel. There’s the heavy influence of Jack London and Henry Williamson, as you would expect from a 20-year-old of the time. We’re in the realms of adventure in the days of empire, and beasts, and stark, one-word titles – ‘Python’, ‘Gorilla’, ‘Rhino’, ‘Cheetah’. Other titles contain fractionally more words: ‘Skogula – the Sperm Whale’; ‘Wang Khan of the Elephants’ (‘Wang Khan was chief of all the elephants who were piling teak for the Amalgamated Teak Company… The great elephant loved his mahout’) and so on, but told economically and honestly, if a little sentimentally.

They seem to me so familiar that I feel I must have seen them anthologised in my childhood, 40 years after their publication, among the books of my father’s childhood library. These are the beasts boys love (they also include condors and sharks). There is violence and death – not revelled in but seen as climactic and inevitable. Had I read ‘Shark No. 26’ as a ten-year-old when it was published in 1934, I’d have relished the pitiless bloodletting and the sheer muscular violence of the animal attacking its hapless victims. I’d have thought ‘Coo!’ (or if feeling bolder ‘Cor!’) and declared it the best story ever written.

It took another 36 years for O’Brian to become famous or even well-remunerated. (There’s a fascinating foreword to this collection by his stepson, Nikolai Tolstoy, with vignettes of rural near-poverty.) If it hadn’t been for that success we wouldn’t have this book to enjoy now.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in