Imagine your donkey and mine graze in the same field. One day I conceive a dislike for my donkey and shoot it: on examining the victim, though, I realise with horror I’ve shot your donkey. Or imagine a slightly different scenario. As before, I draw a bead, but just as I pull the trigger, my donkey – perhaps more invested in this vale of tears than yours – steps out of the firing line and I shoot your donkey.

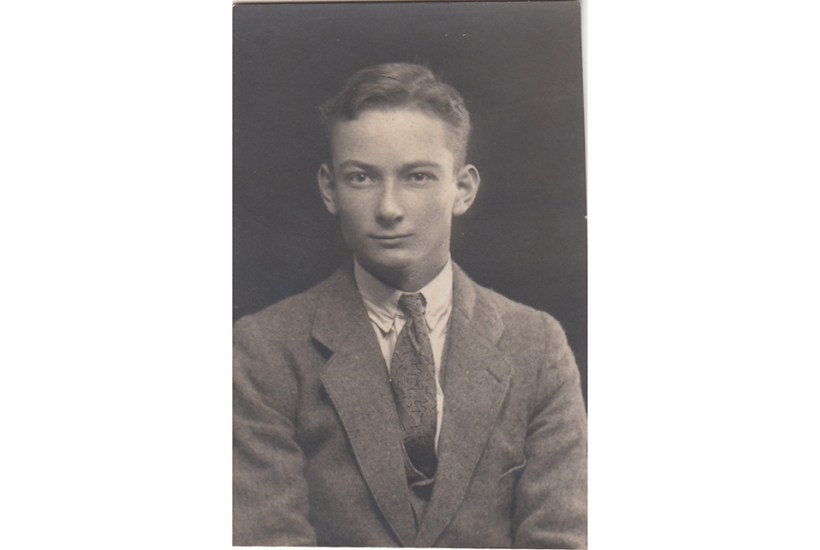

Now here’s the question. When, in either case, I turn up on your doorstep with the remains of your donkey, how should I frame my apology to you? In his 1956 presidential address to the Aristotelian Society, J.L. Austin (1911-1960), White’s Professor of Philosophy at the University of Oxford, a man who, M.W. Rowe estimates in this scholarly yet entertaining and ultimately heartbreaking biography, was the leading philosopher at the world’s leading philosophy department, considered this literally asinine question.

Austin recommended breaking the news thus, with Bertie Wooster-like silliness: ‘I say, old sport, I’m awfully sorry etc, I’ve shot your donkey.’ But what should he say next, Austin asked the Aristotelian Society? Should he say ‘I’ve shot the brute by accident? Or by mistake?’ This was the issue Austin explored with Jeevesian rigour in his paper A Plea for Excuses.

Why, with due respect to imaginary donkeys, did Austin devote his brainpower to their fates? This was a man, after all, who only a few years earlier had been awarded the OBE for doing really important work saving tens of thousands of Allied troops’ lives. During the second world war he rose from the War Office basements of MI14(b), an intelligence outfit devoted initially to frustrating the German invasion threat, and staffed by an array of like-minded brainiacs who, as much as Bletchley Park’s codebreakers, demonstrated something that now seems extraordinary – namely that British intelligence was no oxymoron.

MI14(b)’s head was Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Strong, reportedly brilliant but so chinless he was known as ‘the hangman’s dilemma’. Strong’s staff included not just Austin but Captain the Honourable Richard Maximilian Lyon-Dalberg-Acton, Captain ‘Pooh’ Malcolm, and the startlingly middle-named archaeologist Eric Barff Birley. The last of these had used a card index to identify Roman cohorts at Hadrian’s Wall; at MI14(b) he deployed another for the Wehrmacht, realising that German planners were classicists too and so modelled their divisions according to Roman principles.

Austin was in his intellectual element in MI14(b) and later at the Theatre Intelligence Section, analysing information in many languages borne across the Channel, including by carrier pigeons. From what he read, he realised early that Nazi divisions were moving to North Africa and later provided intelligence that hastened Rommel’s ultimate defeat. More importantly, his detailed analyses (not least of the geological composition of Normandy beaches and precise whereabouts of Nazi guns) effectively decided where D-Day forces landed.

After D-Day, as Allied troops swept eastwards, each soldier carried a little guide book compiled by Austin called Invade Mecum (a nice Latin gag on a vade mecum, or reference book, meaning ‘come with me’). It contained maps and local information so detailed that sappers used it to identify the best crossing points to build bridges key to the war’s successful prosecution.

To be fair to Austin, the body count for donkeys has previous with philosophy. The paradox of Buridan’s ass places the beast equidistant between food and water, positing that it will starve because it can’t choose one nourishment over the other. Austin’s donkeys were invented to incite us to consider hair-splitting differences between mistake and accident. The former seems to be an error in judgment; the latter something untoward happening, possibly after correct judgment has been implemented.

Such fine distinctions were Austin’s speciality, the basis of what he called linguistic phenomenology and what became known as ‘ordinary language philosophy’. ‘Much, of course, of the amusement and of the instruction,’ he told the Aristotelian Society, ‘comes in drawing the coverts of the microglot, and in hounding down the minutiae, and I can do no more than here incite you.’

Austin’s most enduring contribution to philosophy was to attack the idea persisting from Saint Augustine that language’s primary task is to reflect reality. In How To Do Things With Words, he urged us to consider not language’s overrated constative role (eg ‘the cat is on the mat’), but its performative one. Imagine you’re at high table. Someone asks: ‘Is there any salt?’ This utterance is a speech act with three aspects. The illocutionary act is to request salt; the locutionary act is to ask about the salt’s presence; the perlocutionary act is what happens as a result of, ideally, someone passing the salt. Many utterances are performatives. Consider ‘I name this ship Queen Elizabeth’ or ‘I bet you sixpence it’ll rain tomorrow’. Austin, with a precision suggesting he might well have enjoyed a legal career, came up with five kinds of speech acts – verdictives, exercitives, commissives, behabitives and expositives. Rowe considers Austin’s talent for close observation to resemble that of his distant relation Jane Austen.

Austin’s philosophy was influenced by the one developed contemporaneously at Cambridge by Ludwig Wittgenstein until the latter’s death in 1951. Wittgenstein’s method was to demonstrate that philosophical puzzles arose from misconstruing language. Austin’s Darwinian sense was that ordinary language had evolved; it was in good order, but we get our proverbial knickers in a twist when we philosophise. Rather, for instance, than considering ‘knowledge’ as a largely mythical monolith, as philosophers had done, better to reflect meticulously on the various ways we use ‘know’ and its cognates.

But while Wittgenstein was a tortured iconoclast who philosophised best in solitary anxiety, Austin’s method was collaborative and democratic. Rowe suggests that Austin deployed techniques he learned in the army – disciplined meetings, working groups – to make philosophical progress. Philosophical problems, like the difficulties intelligence officers encountered, writes Rowe, ‘can seem not especially glamorous or mysterious, and they can be solved by teams exercising patience and thoroughness’.

But this sounds joyless. Austin’s Saturday morning seminars were anything but. Rowe describes how former students from Magdalen or Berkeley would emerge from seminars with sides splitting. You get a sense of the daffy fun of what went on in those rooms from Austin’s paper Pretending. What is the difference between pretending to be an owl and imitating an owl? Can a thief, posing as a window cleaner, be said to be pretending to clean the windows if, while he cases the valuables in the house, he actually cleans the windows?

Just as Aristophanes ridiculed Socrates for apparent triviality, so naysayers supposed what Austin did was fatuous. But he became the British Socrates, favouring the oral over the written, enjoying argument rather than assertion, and destroying philosophical orthodoxy without presenting an alternative.

Austin made enemies easily. ‘I hated him,’ said Gilbert Ryle, and even Austin’s disciple John Searle recognised that the philosophical world was divided into admirers and haters of Austin, the latter including Wittgenstein’s translator G.E.M. Anscombe, whom Austin called ‘the ninny’, while she, convinced he pinched his best ideas from Wittgenstein, called him ‘the bastard’.

Rowe has great fun narrating Austin’s failed attempt to stop his leading nemesis A.J. Ayer horning in on his Oxford philosophical fiefdom by becoming its Wykeham Professor of Logic. He was chummy with Isaiah Berlin, and no wonder: the latter could be just as bitchy as Austin. ‘Well what are we to make of that pathetic rigmarole?’ said Austin after one unfortunate presented a paper. ‘His desire for power and his dismissiveness of others made him enemies,’ concludes Rowe, ‘and actually impeded the spread of his philosophical ideas; and his refusal to admit … he was ever in the wrong suggested weakness and insecurity.’ He was part Tigger, part martinet.

Before his death from lung cancer in 1960 Austin had been, Rowe estimates, moving on from ordinary language philosophy. He was working with his wife Jean on something called ‘sound symbolism’. Perhaps the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure was wrong in suggesting words are arbitrary signs with no link to what they denote. Austin, contrarily, came up with a plausible suggestion called clustering. A new word is more likely to catch on if it sounds like established words that have similar meanings, he thought. For instance, if you want to introduce an unpleasant signifier, you’d be well advised to start it with ‘sn’, joining thereby snoop, snooty, snigger and snarl.

It is our loss that his thoughts on clustering, along with his pre-war lectures on Aristotle, have never been published. Austin remains one of the few philosophers who can be read with pleasure. Even his translation of Frege’s Die Grundlagen der Arithmetik is improbably fun. He died aged 48. Still, as Rowe puts it, in 30 years of adult life John Langshaw Austin managed two outstanding careers of international importance in largely unrelated fields. Most of us can’t manage one.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in