One of the quirkier books on my shelf is titled Kingwalks: Paths of Glory (Seirawan & Harper, 2021, Russell Enterprises). King safety is a fundamental imperative for chess – after all, checkmate is the aim of the game – so the exceptions where that instinct is best overridden tend to be rather appealing. Probably the most famous example is the game Short-Timman, from Tilburg 1991, in which England’s future world championship challenger marched his king far into enemy territory to assist with a mating attack. But Kingwalks identifies plenty of other possible motives for these adventures. King evacuations (vertically, or horizontally) in the face of an attack are common, but a king might also run away to prepare an aggressive pawn storm on the wing it has vacated. Or a king may act boldly in anticipation of an exchange of queens.

By default, kings get tucked away near corners for their own safety, so it is unusual to see a king needing to get out of the way of its own pieces. Elaborate manoeuvres are extremely rare, such as in the game Oll-Hodgson, Groningen 1993, in which Julian Hodgson moved his king from g8-h7-g6, clearing a path for Rd8-h8-h5-f5.

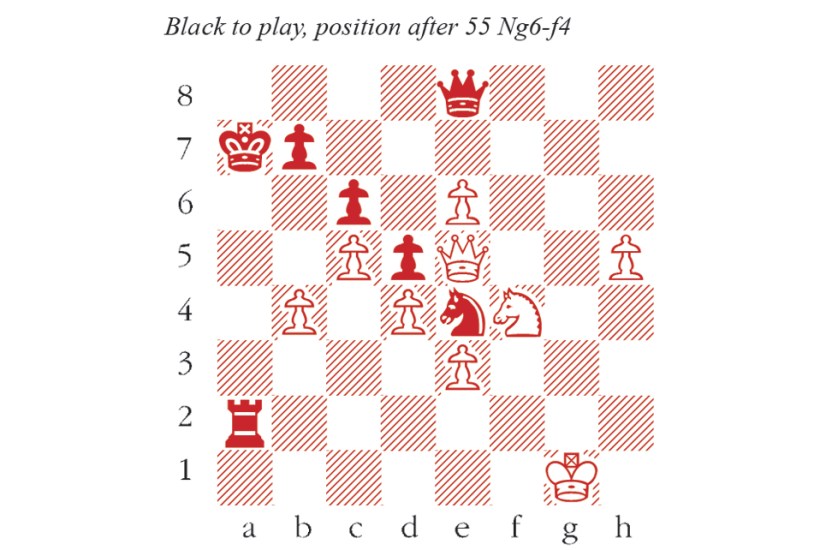

But a curious case arose in the following game from the ECU Senior Championships, which concluded in Acqui Terme last weekend. Almost 20 moves earlier, White sacrificed a rook and hounded Keith Arkell’s king from the kingside all the way to a7. Now it is safe, and Arkell remains a rook up, but both players were down to about a minute or so, and it remains far from obvious how to combat the passed pawns on h5 and e6. 55…Nd2 looks tempting, but 56 Qg7 dodges Nd2-f3+ and prepares to trundle the h-pawn forward. Careful analysis shows some subtle ways to win, e.g. 55…Qg8+ 56 Ng6 appears to restrain the queen, but then 56…Qd8 57 e7 Qd7! 56 e8=Q Qg4+ and mate follows.

But Arkell’s solution was no less effective. Noticing that his queen might instead enter the game down the a-file, he took a radical step to enable that.

Povilas Lasinskas–Keith Arkell

ECU Senior Championship 50+, 2023

55… Ka6! 56 Qg7 A mistaken attempt to prevent what follows, which Arkell ignores, seeing that his king will be safe on c4. 56 h6 was a more challenging alternative. But after 56…Kb5 57 h7 (or 57 e7 Rb2! prepares Qe8-a8-a1) 57…Qa8 58 h8=Q Ra1+ 59 Kh2 Qa2+ 60 Ng2 Qb1 61 Kh3 Nf2+ 62 Kg3 (or 62 Kh2 Qg6!) 62…Qg6+! 63 Kxf2 Ra2+ and mate follows. Kb5 57 Qxb7+ Kc4 White’s queen is overworked, and cannot guard g8 and a8 simultaneously. 58 Qf7 Qa8 59 e7 Qa4 60 Ng2 Ra1+ 61 Kh2 Qd1 White resigns since 62 Kh3 Qh1+ 63 Kg4 Qxg2+ wins quickly.

In the over-fifties championship, Arkell finished in a seven-way tie for first place on 6.5/9, narrowly missing out on a medal with an unfavourable tiebreak score. John Nunn was top seed in the over-65s championship, and took the gold medal with the strongest tiebreak from a group of five players on 7/9. One other member of that group was the strong English amateur Terry Chapman, who could count himself unfortunate only to be awarded fourth place on tiebreak.

The puzzle is taken from Nunn’s final round win against Nona Gaprindashvili, the Georgian former women’s world champion.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in