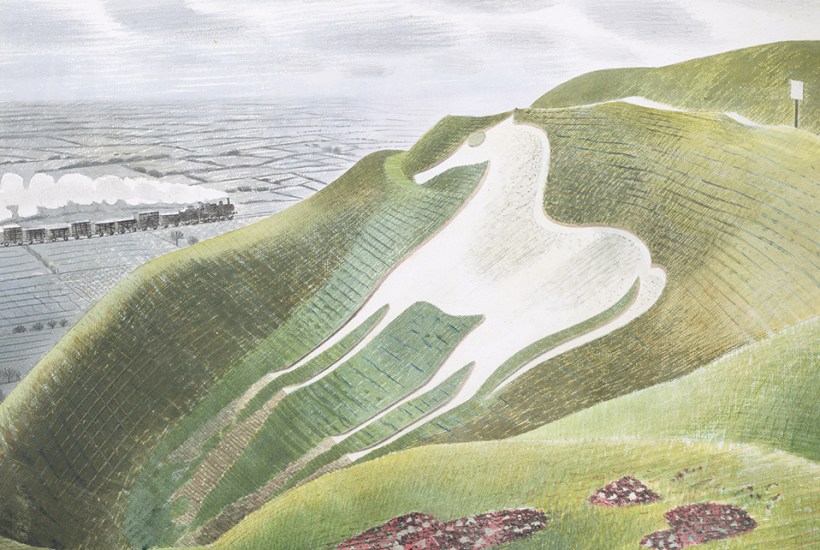

Horses have schlepped, hauled and galloped grooves into Britain, providing the muscle for transport, industry, agriculture and leisure and the inspiration for myth, art and literature. In The Bridleway, the environmentalist Tiffany Francis-Baker maps this busy-storied topography from the Uffington White Horse to ancient roads, canals, coaching inns, race courses, conservation projects and public art. She crosses the country to speak to horse-people and explores old bridleways. Some of the landscapes she visits are subsiding, as she puts it, ‘into the healing bosom of the earth’. Others are threatened with erasure, and so, ‘to keep these spaces full of memory, all we must do is tread the same paths, either on foot or by hoof’.

The charm of her book lies in wayside details. We hear of the Nuckelavee, an Orkney monster that’s part-horse, part-sea creature, and of the 17th-century traveller Celia Fiennes agreeing with her horse that they needn’t visit a foul-smelling spring in Harrogate. Francis-Baker visits a restored cider mill powered by a cob and talks to the photographer Ruth Chamberlain about the ways in which different landscapes have shaped native breeds, from ‘good-doing’ Highland ponies that thrive on little grass to well-thatched Fell ponies keeping warm in Lakeland rain. There’s a lot to take in, and we move at a spanking trot back and forth through the centuries.

But the idiosyncratic bridlepath can be confusing to follow, looping in on itself or stopping abruptly just as the way ahead gets challenging. The author, contemplating the Parthenon Marbles in the British Museum, says they were part of a temple honouring Athena. Next we’re in Athens, and she tells us again that the Marbles’ original home was ‘built as a temple to Athena’. A rare Przewalski horse is a ‘beige, stocky little pony’, and a few lines later a group of them have ‘dun-coloured coats and stocky bodies’. Later, the narrative leaves Britain again to tell the story of an American botanist travelling in Arizona. There are a few slips in time. Hermann Goering is a ‘convicted war criminal’ before the second world war has broken out, and our late Queen is ‘still seen riding through the grounds of her estates’.

There are also paths not taken. Hunting is only mentioned as being abhorred by Lady Florence Dixie, the 19th-century Scottish feminist, war correspondent and renowned horsewoman, although coppicing, enclosure and sporting history are inseparable. The Victorian myth that heavy horses were originally bred for the battlefield is trotted out. In reality, they were the intensively inbred creations of the agricultural revolution, which remoulded not just their bodies but the British countryside itself.

The book often baulks at harder questions. The words ‘power’, ‘powerful’ and ‘empowering’ recur but, other than literal horse-power, we never dig into what this means. Who holds power? How is it maintained or subverted? How does it shape the land, and what does this have to do with horses? Francis-Baker admires the manicured grounds and champagne bars of polo clubs such as Hurlingham and Cowdray, noting that they are surrounded by low-income communities before commenting incuriously: ‘It is nobody’s fault that these spaces have become so exclusive – and many would argue that this is part of their charm.’

That’s as far as we wander into the history of how Asian polo became an elite European sport, or how land has been purposely fenced off for centuries. A later chapter mentions the expense of participating in equestrianism but, other than a brief reference to the Ebony Horse Club in Brixton, we don’t find out much, even though horses were once a cornerstone of working-class livelihoods and pride. Children still keep horses on council estates and even in old railway stables in London, in a world beyond that of £75-an-hour riding lessons. Francis-Baker does devote much space to the British gypsy, Roma and traveller communities, but hands over the reins to her interviewees, the author Damian Le Bas and the poet Raine Geoghegan.

We’re on surer ground in the chapter about pit-ponies and quarries. On Dartmoor, a lost landscape of metal extraction is evoked, peppered with ‘blowing houses’, where pack- and wagon-horses traipsed like trails of ants between mine, furnace and road. Also described is the 200 metre-long pit-pony sculpted from waste coal shale by the artist Mick Petts in the Rhymney Valley in Wales, whose hoofprints turn into rainwater pools buzzing with insect life.

Towards the end of the trail, Francis-Baker visits the rewilded Knepp estate in West Sussex, where a herd of Exmoor mares graze the flora into the right shape for the fauna and provide a good illustration of how horses choose to live – amicably, peace-ably – when left to their own devices. ‘Our connection with horses continues to root us in the collective human experience,’ she concludes – perhaps even more than her book acknowledges.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in