‘The most nuked place on Earth…’ This is how the Semipalatinsk 18,500 square km testing ground on the Kazakh Steppe is described.

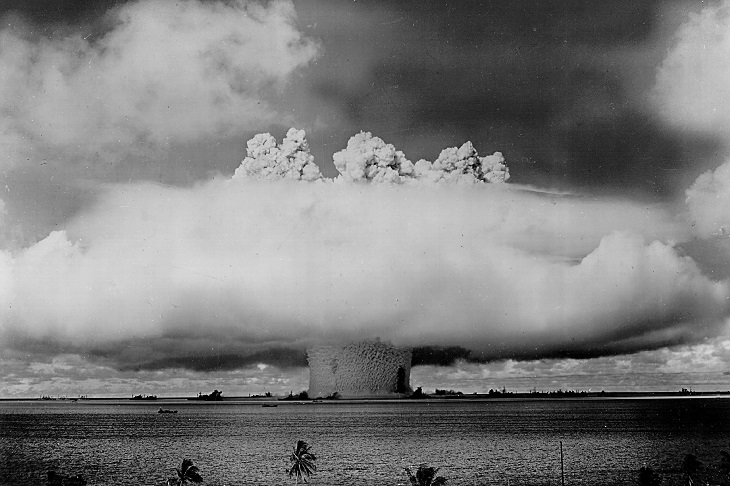

It was here that the Soviet Union brought its weapons of mass destruction out to play and by the time it was abandoned, a full quarter of the world’s nuclear bombs had been exploded in the region. Google Maps reveals an area smattered with craters and deep scars on a landscape that has yet to recover from a punishing forty-odd years. The damage includes a river that had its course permanently and deliberately altered back when the Soviets thought nukes would make light work of industrial projects.

As reported, ‘During the period 1949-89 the former Soviet Union conducted about 460 nuclear weapons tests within the test site […] five of these surface tests were not successful and resulted in the dispersion of plutonium in the environment.’

The Soviets didn’t care what happened to the locals, who were blown off their feet and covered in radioactive debris without so much as a warning. Poor and uneducated nomadic families who lived closer to the test site assembled to watch the bright lights that flickered in and out of existence accompanied by earthquakes. Soviet management claimed ignorance about the 40,000-odd local inhabitants of the steppe, but others doubt that is possible.

While we may never know what took place in the hearts of the men leading the weapons program, nature took an unkind turn with strong winds carrying radiation across the land resulting in premature death, cancer, and birth defects with over 1.5 million people believed to be directly impacted. Russian leadership was single-minded in his pursuit of nuclear supremacy over the Americans and so Kazakhstan became an open-air lab for weapons testing and a source of gulags and slave labour. It was here that the world progressed its knowledge in radiation sickness, but in secret, of course.

Released in this area was the 1955-era RDS-37 (with RDS-1 being the first) – a two-stage hydrogen bomb of roughly 3 megatons (that was tested at 1.6 megatons).

One of its creators was recently found hanged in a Moscow apartment by his 67-year-old daughter. Russian investigators believe that the 92-year-old Grigory Klinishov ended his life on June 17, with a suicide note being retrieved from the scene. He was, according to those who knew him, mourning the death of his wife.

According to Moscow:

‘A note was found next to the scientist, on whose neck injuries characteristic of hanging were found. The reasons for the suicide could be the severe illness of the scientist and the death of his wife.’

That hasn’t stopped speculation spreading across the region, after a string of suspicious high-profile deaths occurred. Tragedy or murder? We may never know.

Born in 1930, Klinishov received the Lenin Prize in 1962. He was responsible for the creation of a charge fitted into the bomb along with several types of other charges used in the next generation of nuclear weapons. It was a significant contribution to the weapon industry and the evolution of physics. Klinishov worked during an era that pushed the limits when it came to experimental physics. Unfortunately these talents were directed at taking human life under order of the Russian leadership. In the Soviet Union, it was also a period of extreme secrecy, with much of his work conducted in the shadows.

Klinishov is one of the last of his kind with very few people left who took part in this period of madness. They call this a closing of history’s chapter, but we would do well to remember the lessons these scientists learned while quite literally playing with fire. It’s hard to believe, but when humanity first started exploring nuclear weapons, there was a genuine concern that the detonation of such a device might set the atmosphere on fire. Even the genocidal Germans were worried.

‘Heisenberg had not given any final answer to my question whether a successful nuclear fission could be kept under control with absolute certainty or might continue as a chain reaction. Hitler was plainly not delighted with the possibility that the Earth under his rule might be transformed into a glowing star.’

On the other side of the world, American researchers at the Manhattan Project were eventually confident in their calculations that while it was technically possible to vaporise the Earth, it was highly unlikely where ‘the energy losses to radiation always overcompensate the gains due to the reactions’ and that, ‘it is impossible to reach such temperatures unless fission bombs or thermonuclear bombs are used which greatly exceed the bombs now under consideration’.

Another report in 1959 finished with the slightly unsettling:

‘If, after calculation, [Compton] said, it were proved that the chances were more than approximately three in one million that the earth would be vaporised by the atomic explosion, he would not proceed with the project. Calculation proved the figures slightly less – and the project continued.’

Thankfully the Soviet Union didn’t pick Kazakhstan to test history’s most powerful nuclear weapon, the Tsar Bomba. That honour went to the icy island wilderness of Severny. Proving that ‘life finds a way’, it’s back to being a wildlife sanctuary after basking in the glow of what was essentially a momentary star.

The upscaling nuclear weapons was considered one of the world’s most dangerous periods. Today, it could be argued that we find ourselves in a similar situation with the manipulation of bio-weapons in labs around the world. At least nuclear weapons are easier to track and monitor than an invisible weapon piggy-backing on innocent citizens. The sheer spectacle of nuclear weapons concerned all involved. Demonstrations of their supernatural power ultimately led to their undoing, with the scientists involved backing away from what they called god-like chaos.

The breaking point for this power was Russia’s Tsar Bomba.

The original design for the Tsar Bomba to break the 100 megaton range. Even its designers were concerned – so concerned that the uranium layers were replaced with lead in an attempt to cut its output by half. Its eventual explosion, likened to the birth of a star on Earth, terrified the whole world into ending the nuclear arms race. No one was more vocal than the project’s lead scientist, Andrei Sakharov.

It was the point at which humans said, ‘Okay, that’s probably enough now…’

As we ask questions about the departure of Grigory Klinishov, it is difficult not to feel as though we are seeing the final curtain drawn on one period in history with the next waiting around the corner. We have new leaders in various nuclear nations itching to demonstrate their perceived regional dominance as a tangible fire in the sky. North Korea, China, and Pakistan are all on the shortlist of those who may jump first.

As for Kazakhstan, brutalised by its nuclear history and subsequent activist moments, it became upon its independence from the Soviet Union the world’s fourth largest holder of nuclear weapons. It gave these up in the 90s and convinced other nations to do the same. Today, Kazakhstan sits on a huge uranium source which it mines, making itself a global leader in the production of fuel for nuclear reactors. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has fundamentally changed Kazakhstan’s approach to Moscow, with its leadership saying that it does not wish to be trapped behind a new iron curtain. Considering Kazakhstan’s distaste for nuclear weapons, it has moved to condemn Russia for its threats of nuclear war.

The region that carries with it the scars of Klinishov and his fellow team of physicists once again finds itself in the middle of rising geopolitical tensions where the shadows of old empires are rubbing against the brand new ambitions of authoritarian regimes. Humanity played with fire once, perhaps we are about to strike the match again.

Flat White is written and edited by Alexandra Marshall

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in