Are you ready class? The chemistry lesson is about to begin.

Those are words that I never thought that I’d be using to begin a Spectator Australia article, but here we are. Whether we like it or not, chemical terminology has now entered our lexicon – I refer of course to ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ – terms that a Chemistry student would encounter when studying Organic Chemistry at 100 level.

Well, what do they mean, and to what extent can the properties of ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ molecules teach us things about ‘cis’ and ‘trans’ people?

Organic Chemistry is a discipline that is wholly devoted to carbon-based molecules, given carbon’s unique ability to behave like molecular Lego bricks and join to itself in a literally endless number of ways. Also like Lego, the size of these molecules can vary from simple molecules such as methane, containing one carbon atom, to complex molecules such as DNA which contain millions.

One of the ways they can vary is in their physical structure. Two molecules may contain exactly the same number of atoms, but be nonetheless different molecules. The term for these molecules is ‘isomers.’

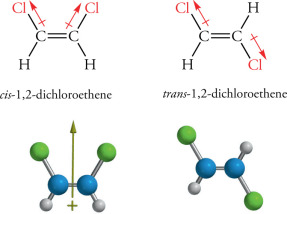

There are many different types of isomers, but the ones that are most relevant to us here are geometric isomers. This is where a molecule has been derivatised with atoms that have different orientations around a double bond.

A simple example is 1,2-dichloroethene: The chlorine atoms may either be on the same side as each other (the ‘cis’ isomer) or on opposite sides (the ‘trans’ isomer).

Well, so what? Why does the orientation of the chlorines matter?

It matters because it bestows upon them fundamentally different properties. There are separate data tables for each of these two isomers because of this. They have different freezing and boiling points and dipole moments, as well as substantially different reactivities. For example – and read into this what you will – the cis isomer is the more stable of the two (by a significant 400 cal/mol if you must know).

And so the modern gotcha question, ‘Is a trans woman a real woman?’ may be simply answered. If by ‘real woman’ we mean someone born with female reproductive organs – a so-called ‘cis woman’ – then the question simply resolves into this – ‘are cis and trans the same?’

The answer is a resounding, obvious, and inescapable ‘no’. Cis and trans molecules are fundamentally different, and that is the very reason the terms exist.

Perhaps the best answer to this question that I’ve heard comes from Richard Dawkins. It’s the answer of a scientist and is pretty much the same answer I’d have given: ‘Well, it’s a semantic question. If you’re talking about biology, the answer is no, as men have XY chromosomes and women have XX chromosomes. If you’re talking culturally, you can say yes, if you think it’s okay to define your gender as you please.’

I, however, would have added: ‘If you’re talking functionally, the answer is also no, as trans women are, on average, bigger and stronger. They also do not menstruate, and cannot bear children. So if you think it’s okay to use definitions that have no basis in observable facts, then yes, you can say that ‘trans’ women are real women.’

But don’t expect that mindset to catch on in chemistry labs anytime soon. If it does, however, if the day comes when I hear, ‘We no longer recognise geometric isomers – we don’t want to discriminate against trans isomers!’ I will take my two degrees, along with all my chemistry textbooks, and make a bonfire out of them…

Dr Mark Imisides @ThugRaffles

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in