In middle age you’re supposed to feel nostalgia for your youth, but I finished this book marvelling at how dreadful the 1980s were. The decade hit rock bottom in May 1985 when, within 18 days, 56 football fans died in a fire at Bradford City and 39 in crushes before the Liverpool-Juventus match at the Heysel Stadium. All through, though, the 1980s lived up to one of Roger Domeneghetti’s chapter titles, named for The Barracudas’ song of 1981: ‘We’re living in violent times.’

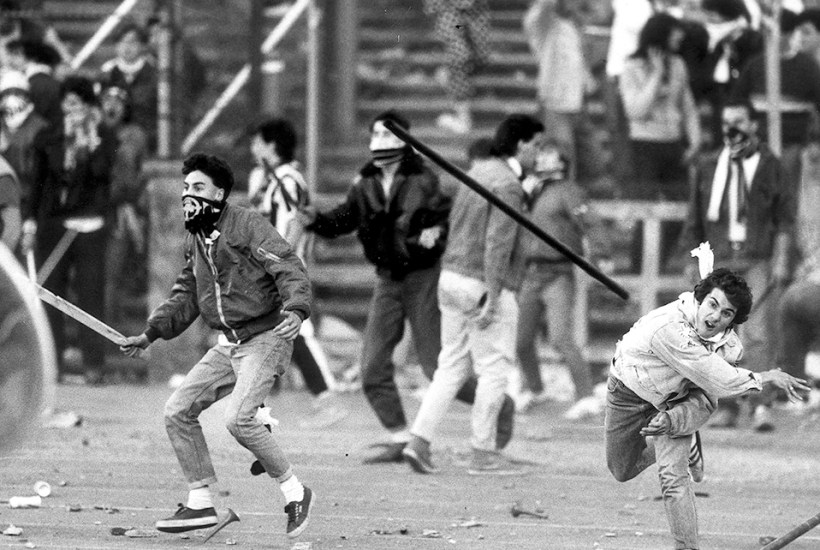

The author, a journalist and academic, has an ambitious premise: sport is the key to understanding what really happened to Britain in the 1980s. The book doesn’t quite live up to that, but it does show how sporting and social dysfunction intertwined. It’s customary, for instance, to think of football hooliganism as a standalone malaise. Domeneghetti puts it in the context of a bloody decade. The pitched battles of the miners’ strike ended just two months before Bradford and Heysel. That autumn of 1985, Birmingham, Brixton and Tottenham erupted in deadly riots against the police. There were frequent fights even at music festivals and in market towns, when the pubs emptied. The journalist Tony Evans, who was at Heysel as a Liverpool fan, told Domeneghetti: ‘People, especially young men, were more attuned to violence than they are now. On your TV news every night you were seeing scenes of street-fighting from Belfast and Derry. Violence was normal.’

Similarly, Domeneghetti places the Bradford fire in the litany of 1980s infrastructure disasters: the British Airways jet headed for Corfu that burst into flames on the runway at Manchester in August 1985 (55 dead); the Herald of Free Enterprise ferry capsizing in 1987 (193 dead); the fire at King’s Cross station months later (31 dead); the explosion on the Piper Alpha oil rig in 1988 (167 dead); and the crush that killed 97 Liverpool fans at Hillsborough in 1989. The South Yorkshire police, who paid compensation to wrongly arrested and assaulted miners after the ‘Battle of Orgreave’ in 1984, were culpable again at Hillsborough. Assuming that the fans trying to escape on to the field were hooligans, it kept them penned in, and even while the disaster unfolded told slanderous lies about them to journalists.

Human life wasn’t always judged cost-effective in Margaret Thatcher’s deregulated Britain. After the Marchioness pleasure steamer sank during a party on the Thames, months after Hillsborough (51 dead), James Tye, the founder of the British Safety Council, remarked: ‘It is no use putting these accidents down to acts of God. Why does God always pick on badly managed places with sloppy practices?’

The Bradford fire certainly wasn’t an act of God. It wasn’t God who allowed decades of rubbish to accumulate beneath Valley Parade’s main stand. The official verdict was that the debris caught fire after a spectator dropped a lighted match or cigarette. As the fire began to smoulder, one spectator went looking for an extinguisher. But, writes Domeneghetti, ‘it was kept in the clubhouse at the far end so it couldn’t be used as a missile by hooligans’. Then flames suddenly engulfed the stand, while fans in the paddock chanted: ‘Piss on it!’ With ITV broadcasting the carnage live, Domeneghetti describes viewers watching ‘one man calmly walking from the stand fully ablaze’.

Twelve-year-old Martin Fletcher escaped the fire, but his brother, father, uncle and grandfather didn’t. Thirty years later, Fletcher wrote a book that cast doubt on the dropped-cigarette theory. He revealed, as Domeneghetti recounts, that ‘in the 18 years prior to the fire, eight businesses that the club’s chairman Stafford Heginbotham had owned or been closely involved in were destroyed in fire. Valley Parade was the ninth.’ Fletcher asked: ‘Could any man really be as unlucky as Heginbotham?’ After the fire, Bradford City received insurance payouts and grants of nearly £1 million.

Football had been losing popularity even before Bradford and Heysel. Just after midnight in late April 1985, 18.5 million people were still awake to see Dennis Taylor win the snooker world title at Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre. The number was more than that season’s total attendance at all English professional football matches. After the tragedies, football practically disappeared from TV screens. In autumn 1985, when West Ham United’s Frank McAvennie was the leading scorer in England’s top division, he could stand on Waterloo Bridge unrecognised. Snooker, American football and even darts briefly outshone football.

It didn’t last. After Heysel, hooliganism – and violence more generally – began to fade from youth culture. After Hillsborough, British football renovated its stadiums. In 1992 Sky plastered the new Premier League across TV screens. Other sports didn’t stand a chance.

Domeneghetti’s writing is occasionally clunky, but this comprehensive document of an era ranges from the Moscow Olympics and the aerobics boom through the many forms of 1980s bigotry to apartheid South Africa’s sportswashing strategy. The book illuminates our own time, too. Britain has been through a rough decade – austerity, a divisive Brexit, lockdowns and plunging living standards – yet has remained bizarrely peaceful. It almost makes you think that societies advance.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in