In November 2010, China’s Dagong Global Credit Rating Company did the unthinkable. The rating agency founded in Beijing in 1994 removed its highest-possible (AA) rating on US government debt, citing ‘serious defects’ in the US economy.

Those aware of Dagong’s decision shrugged off the rationale. They knew the agency was furious about a US decision to refuse it a licence to operate in the US.

But wait. Within nine months, S&P Global Ratings of the US did likewise. S&P withdrew for the first time its ‘risk free’ AAA rating on US debt due to a fight between a Republican-controlled Congress and a Democratic President over Washington’s borrowing limit.

S&P’s statement in August 2011 that:

‘The gulf between the parties’ undermined its confidence in their managing US finances battered stocks, bonds, and consumer confidence. The surprise was that S&P’s decision came four days after President Barack Obama had signed into law a bill to raise the US ‘debt ceiling’.

The what? The term refers to the artificial legal restriction the US imposed on itself in 1917. In an almost Marx Brothers farce, Congress must give the executive permission to borrow the money it needs to pay for programs Congress has already approved. Otherwise, Washington defaults. In other countries, debt authorisation is part of the budget process.

Since 1917, Congress has raised the ceiling about 100 times – 78 times since 1960 is the official count – but not always smoothly. In 1953, Congress hesitated over raising the limit for the first time because lawmakers baulked at funding a national highway system. In 1985, 1990, 1995-96, 1997, and 2011, to cite other notable showdowns, increases in the ceiling were tied to fiscal tightenings. During the 1995-96 feud, the federal government twice shut down. The fight of 2013 led to the limit being suspended for the first time before it was increased without conditions.

The history of debt-ceiling fights will have a 2023 edition. On January 19, Washington bumped against its legal borrowing limit of US$31.381 trillion (a tally that includes US$6.2 trillion the US government owes itself). Congress needs to raise the barrier to cover Washington’s fiscal deficit, which is forecast to 5.8 per cent of GDP this year.

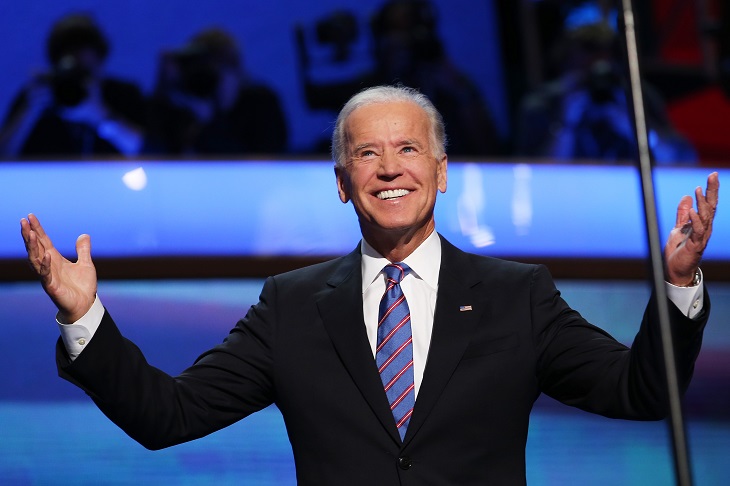

But the Republican-controlled House of Representatives wants to tackle the continuous federal fiscal deficits since 2002 that have boosted Washington’s debt (excluding the amount the government owes to itself) to 98 per cent of GDP, from 35 per cent in 2001. The confrontation is that President Joe Biden says he will only sign a bill that raises the debt limit unconditionally.

The 2023 episode of ‘debt-limit chicken’ has shaped as the most likely to explode into a US default. The polarisation poisoning US politics means neither side’s supporters will accept a backdown. The Republican House majority of just 222 to 213 and the linked shakiness of Kevin McCarthy’s speakership have emboldened GOP debt hardliners.

Their influence was apparent when the House on April 26 passed by two votes a bill that offers a conditional increase in the debt ceiling. But the terms in the Limit, Save, Growth Act of 2023 are unacceptable to Biden, especially the ones that gut his green agenda.

But let’s assume the most likely outcome that House Republicans and Biden somehow agree to raise the debt ceiling and the US default looming in June is averted. Doom skirted, right?

In large part. But, just as repercussions flowed after the debt-ceiling resolution in 2011, this debt showdown has exposed four issues that come with costs for the US and the world.

The first is the precarious nature of US finances has been highlighted. Washington last recorded a fiscal surplus in 2001 and none is in sight. If all government taxing and spending remain in place, the Congressional Budget Office forecasts Washington’s debt to reach 119 per cent by 2033 and to soar to 195 per cent by 2053. The government’s true financial mess might be more acute because the trust funds that pay aged pension and medical bills for seniors (Medicare) are forecast to become insolvent.

The second problem is the rating agencies might still downgrade the US, a la 2011. At a time when the US banking system is wobbling partly because US bond prices have fallen enough to erode bank capital buffers, another thump to US Treasuries (meaning yields rise) would be destabilising for banks and the economy.

The third issue magnified is that US politics is so dysfunctional the federal government can’t guarantee it can meet debt repayments on time. Politicians are prioritising bluster over the comprise that lubricates the US political system. Once the ceiling was hit in January, it took nearly four months until Biden met McCarthy.

Another political hurdle is neither party will touch politically sensitive outlays such as social security and Medicare. That this spending come under the 62 per cent of federal outlays deemed ‘mandatory’ because they fall under laws set outside the budget process means spending cuts must focus on ‘discretionary’ items. Too hard.

The fourth problem is the episode undermines global support for the US dollar’s unrivalled status as a reserve currency. US foes are already searching for alternatives to the US dollar due to how Washington has weaponised the US financial system by enforcing sanctions. It’s not just China, Iran, and Russia looking for alternatives. Even Southeast Asian countries are considering an Asian Monetary Fund that would pool regional currencies to ease away from the US dollar. Turning away from the US currency means less demand for US-dollar securities.

The world’s problem is the global roles played by the US government, economy, Treasuries and dollar are irreplaceable for the foreseeable future. The global financial system, which is built on inherently unstable fractional-reserve banking, is weaker than people think.

To be sure, come any crisis, investors will pile into US Treasuries and boost the US dollar because they are the best havens around and the Federal Reserve is still trusted. But that’s a reflection of the weakness of the alternatives. Any rating downgrades, which are unlikely, to be sure, might only have a modest impact on interest rates. The brinkmanship over the US debt ceiling has always been resolved. What’s changed?

Just that the more US debt chicken is played, the more likely is a bad end. As Dagong warned 13 years ago, the US has ‘serious defects’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in