Aspirin, a greasy fry-up, even hair of the dog – all are popular options when nursing a hangover. The last thing you would choose to do is play a long game of chess, but that’s exactly the pickle in which Magnus Carlsen found himself during the first round of the 2012 London Chess Classic. The world number one had celebrated his 22nd birthday the night before, but dinner and bowling ‘turned into something else’ as he shared on the Norwegian podcast Sjakksnakk a few weeks ago.

Carlsen shambled into a wretched position, but was granted a lifeline after one poor move from his opponent in the middlegame: ‘All of a sudden I felt like my whole hangover just got cured.’ The rejuvenated Carlsen decided it would be ‘epic’ if he managed to win the game. And so he did, thanks to some formidable technique featuring an unlikely king march in a complex endgame with queens on the board.

His opponent, alas, was me. But chagrined, I am not. Carlsen’s story tallies with my own experience, which is that my chess performance in supposedly impaired states is nowhere near as bad as it ought to be. I too have won a game with a hangover, in a manner which made me rather satisfied. I don’t plan to repeat the experience, but getting ill is harder to avoid and has much the same effect. As creative constraints go, the need for extreme economy of brainwork is not too bad. You fall back on trusting your gut, and rediscover the truth that intuition is only slightly inferior to the contrivances of conscious thought.

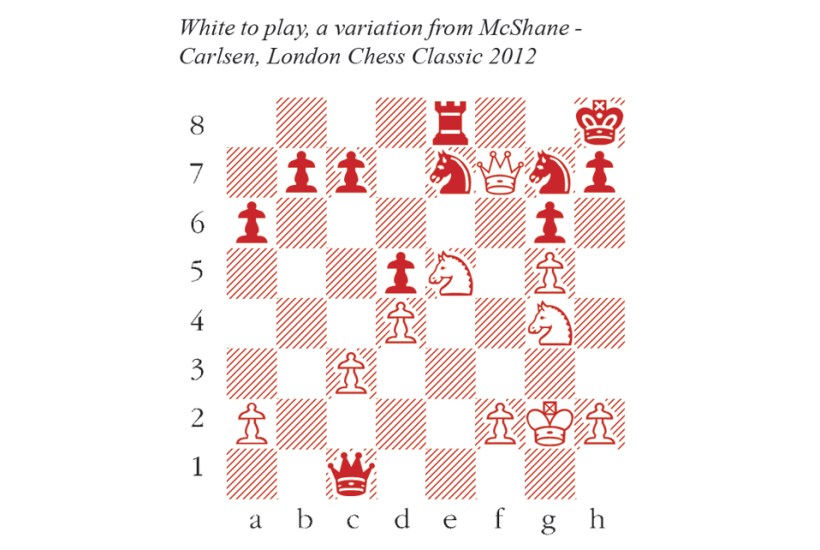

A case in point arose during that game against Carlsen. On my 26th move I advanced my knight from f3 to e5, in order to attack his queen on d7. While considering it, I spotted one of the most enjoyable checkmating ideas I have ever seen at the board (see diagram).

The position in the diagram never occurred in the game, but shows the moment which I imagined after a long sequence of moves involving a rook sacrifice. (The full game score is available online, and the hypothetical sequence of moves was 26…Qb5 27 Qf3 Qxb2 28 Bxg7 Qxa1+ 29 Kg2 Nxg7 30 Qxf7+ Kh8 31 N3g4 Qc1.)

White gives mate with 32 Qg8+! Kxg8 (other captures allow Ne5-f7 mate) 33 Nh6+ and then 33…Kf8 34 Nd7 mate or 33…Kh8 34 Nf7 mate.

Beautiful as this is, it was a misguided extravagance. White had better options than sacrificing a rook, while Black had a better defence available afterwards. As they say, ‘long variation, wrong variation’.

I shared these moves with the press conference after the game, whereupon Carlsen caused some amusement by stating that he hadn’t seen any of it, and rejected 26…Qb5 on the mundane grounds that I could play 27.b3. Such is the wisdom of a hangover.

Instead, he responded by simply shunting his queen from d7 to d6. I am sure it is no coincidence that my cognitive bender was so swiftly followed by a serious oversight. My very next move was the one which granted him the tactical opportunity he needed to turn the game around. He went on to win the 2012 London Chess Classic, thereby eclipsing the record international rating set by Garry Kasparov in 1999.

I found an article on the Daily Mail website from that very week, which included an intriguing detail. ‘Carlsen’s manager Espen Agdestein said he didn’t anticipate his client would be devoting any time to enjoying a few glasses of champagne to celebrate the landmark because he was “a bit boring in that regard”.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in