Irreligious tolerance

Sir: Your editorial ‘Crowning glory’ (6 May) celebrated the religious tolerance in Britain that will permit a multifaith coronation. However, it didn’t acknowledge that in modern Britain nearly half of people have no religious belief. This acts as a buffer, making religious differences of opinion of less importance. Britain is one of the least religious countries in the world. In more strongly religious countries, such tolerance is harder to find.

Michael Gorman

Guildford, Surrey

Admirals on horseback

Sir: If Admiral Sir Tony Radakin only had to march at the coronation (Admiral’s notebook, 6 May), he was fortunate. At the 1953 coronation, Lt Cdr Henry Leach (later Admiral of the Fleet Sir Henry Leach) was in charge of the naval element. Precedent required admirals to take part on horseback, but the best the Navy’s parade training specialists could come up with, when asked to advise on protocol, was a 1905 document advising sailors that horses were steered like a boat, but with reins instead of rudder lines. At one of the rehearsals, the Controller of the Navy was thrown from his horse and concussed, while on the day itself the First Sea Lord’s horse got restive and carried its rider through Admiralty Arch ‘beam on’ – at a right angle to the direction of travel.

David J. Critchley

Winslow, Buckinghamshire

Immigration numbers

Sir: The fundamental reason for the concerns expressed in Douglas Murray’s article (‘The cost of mass migration’, 6 May) is that two points of view, both of which favour higher immigration, have come to dominate the argument. The first can best be described as the ‘moral case’ – that we owe it to people less fortunate than ourselves. The other is the ‘economic case’, which has led British industry to favour cheaper foreign labour at the expense of the settled population.

There is some merit in both arguments, but there has yet to emerge any focused counter view expressed on behalf of the 67.3 million people already settled here – including 18 per cent from minority ethnic groups. Their concerns include economic worries (in particular that the increase in our national GDP has not been fairly shared) but also quality-of-life factors.

When I formally polled this across all ages, social grades, regions of the UK and voting preference, about 60 per cent were concerned about future population growth, 51 per cent thought that there should be a cap on the level of net migration, and more than 60 per cent were concerned at the failure to plan for future population growth. Where are these views represented? No one doubts the cultural and economic value of some immigration. The debate is about numbers – an increase in our population of more than eight million in the past 25 years.

We urgently need to establish a way to debate the trade-offs in a dispassionate, evidence-based manner. Last year I tabled a Private Members’ Bill to establish an Office for Demographic Change to do just that. I urge all parties to consider it as part of their upcoming manifestos.

Robin Hodgson

House of Lords, London SW1A

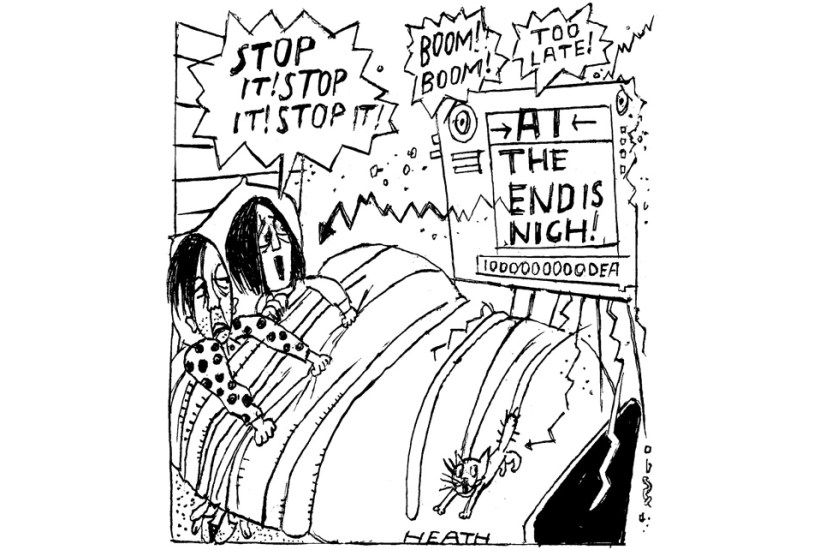

The real AI threat

Sir: Geoffrey Hinton argues that AI will one day rise up and overthrow its masters (‘We may be history’, 6 May). Yet the real threat is not to our security, but to our souls. AI’s wild promise is that it will perform creative tasks for us – millions of paintings, films, stories, articles, music and lines of code per second. But the reason someone learns to paint is not merely to produce paintings; it is to become a painter. The patience, discipline and attention required for creativity is formational as well as productive. Our skill does not simply make things for us; it makes us who we are.

The digital age has already chipped away at our capacity for attention and deep, empathetic relationships. If AI tells us there is no need for us to learn creative skills, then it has already begun to destroy us. As Psalm 115:8 says, the manufacture of mute and mechanical idols eventually creates mute and mechanical people: ‘Those who make them become like them; so do all who trust in them.’

Nathan Weston

Lancaster

Shiny Metallica

Sir: I’ve never found myself out of alignment with Rod Liddle until his recent review of Metallica’s 72 Seasons (Arts, 6 May). He is at least mostly right. It is shiny, tight, smooth, and nothing much has changed. But lack of change isn’t a bad thing, and it’s not for dispossessed incels. We (the middle-aged, middle-class, repressed by society’s norms) aren’t looking for riffs that touch the sides. We appreciate the familiar weight and momentum that carries us towards a promised conclusion. Mostly it’s not there. Sometimes it is though.

James Dutton

Ash, Surrey

The invention of diesel

Sir: I defer to Rory Sutherland on most topics, but he is wrong to state that the diesel engine isn’t a British invention (The Wiki Man, 6 May). The Englishman Herbert Akroyd Stuart filed his patents for a heavy oil engine in 1890, two years before Rudolf Diesel’s. There were other claimants too. By 1892 Akroyd Stuart had a heavy oil engine on sale commercially in partnership with Richard Hornsby & Sons, six or seven years before Diesel brought his design to market. He deserves proper recognition.

Andrew Dent

Ditchley, Oxfordshire

Leagues ahead

Sir: Toby Young is wrong to say Manchester City are on course to become the first club to win the Premier League three years in a row (No sacred cows, 6 May). Manchester United have won three titles in a row twice, between 1999-2001 and 2007-2009.

Cllr Calum Davies

Cardiff

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in