On Tuesday afternoons, pathology teaching at medical school required me to peer down a microscope for two hours, screwing my inactive eye ever more tightly shut as if that would make the looking eye suddenly see clearly. Each eosin-stained slide with its pink and purple lines and splodges of diseased cells was as legible to me as a barcode. The tiny world beneath my lens created an illusion of human supremacy, a world where the truth was small, immobilised and bored of itself.

Pathogenesis – the cause of disease, its development and the impact it has on cells and organisms – is thankfully not what Pathogenesis is about. Jonathan Kennedy is a sociologist, not a microbiologist, and his unit of interest is the epidemic event, not the single bacterium. Where tales of great white men, great inventions and great power once populated the history books, Kennedy argues that great plagues are what really matter. Immunity has been the unifying asset of survivors and victors. The historical sweep of his pen could not be wider, from pre-history to post-Covid. Three hundred-odd pages roam through 50,000 years, and by the last it’s almost impossible to disagree that infectious diseases are our permanent companion and ultimate adversary.

Humans are not always in competition with pathogens, though. In fact our existence is indebted to them. A viral infection hundreds of millions of years ago might have enabled our brains to form memories, because of the insertion of a heritable piece of DNA that codes for ‘tiny protein bubbles’ to assist information transmission between neurons. Moreover, the fact that we’re not nibbling at the shells of our mothers’ eggs is because ‘a shrew-like creature developed the capacity to gestate her young inside her own body’. Thanks to a retrovirus, mammals were gifted the placenta and the relative safety of pregnancy.

As possibly the only person not to have read the 2014 mega-hit Sapiens, I was intrigued by the more speculative sections of deep history on different human species. For 250,000 years, Homo sapiens lived alongside other humans, including Homo erectus, Neanderthals and Denisovans. It was only 40,000 years ago that Homo sapiens spread across the world while fellow species became extinct. Emerging evidence suggests Homo sapiens in fact reproduced with other human species, and today approximately 2 per cent of our genes comes from Neanderthals. We know about these meet-cutes because of archaea found in calcified plaque on Neanderthal teeth, which could speculatively have been transmitted through kissing, and this same archaeon is a cause of modern gum disease. The evolutionary advantage of genetic mixing of the two species’ microorganisms gave Homo sapiens resistance to unfamiliar diseases and a lifeline for survival and dominance.

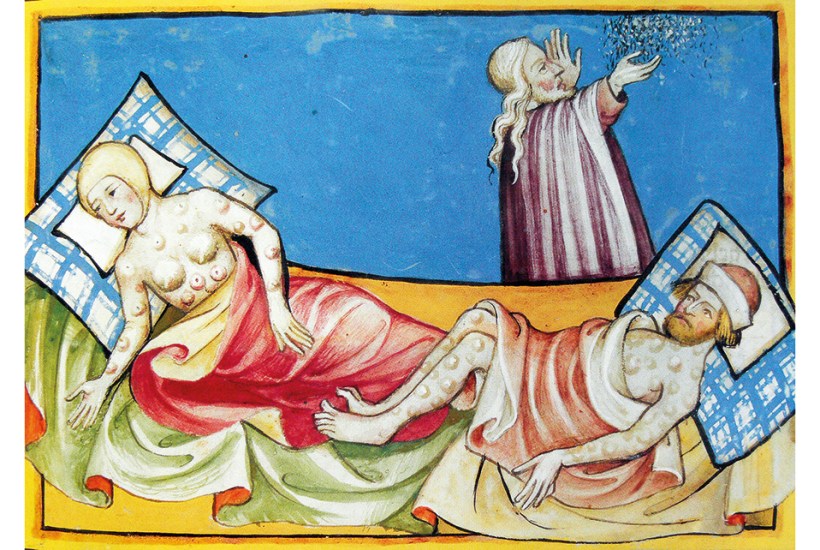

The fluency of Kennedy’s narration is remarkable, weaving Tolkien, Game of Thrones and Monty Python into memorable and accessible explanations of genetics, evolutionary biology and demography. Whether looking at hunter gatherers overwhelmed by new zoonotic diseases, Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War and the role of plague in Sparta’s victory, or the 60 per cent decline in Europe’s population from 1348 due to the Black Death, each era in history seems to hinge on infectious disease as a ‘devastating weapon of mass destruction’. The result of recurrent infections and exterminations is that ‘contemporary Europeans are neither genetically “pure” nor are they the region’s indigenous people. Even white Europeans are mongrel immigrants.’

Events across the Atlantic further strengthen Kennedy’s point. When the Spanish arrived in the New World, their exposure to domesticated animals and denser populations back home gave them the upper hand in encounters with natives who didn’t enjoy such immunity. Kennedy perhaps oversimplifies this ‘virgin soil hypothesis’, as historians of medicine have emphasised the role of social factors and living standards too. But Old World pathogens did result in a 90 per cent fall in the population across the Americas, far outranking damage from imperial force. Smallpox, malaria, yellow fever and measles were the true, though unconscious, armamentarium of the colonisers. African immunity to malaria went on to fuel the racist ideology used to justify human trafficking across the Atlantic during the slave trade and became the foundation for economic arguments to exploit their labour.

Kennedy wears his politics on his sleeve, as well as his despondency. The idealism that inspired the WHO, established in 1948, was corroded when the US and UK in the 1980s, under Reagan and Thatcher, reduced their contributions to addressing the global burden of disease. Today, ‘vaccine colonialism’ means that antiretroviral drugs are stockpiled in wealthy nations, but are relatively scarce in poorer ones. Inequality also thrives at home, where a man’s life expectancy in Blackpool is 27 years less than a man living in Kensington and Chelsea – the same difference between the UK and the most deprived countries in Africa. However, the West’s big killers are cardiovascular disease, cancer and Type 2 diabetes. Although not transmitted like a virus, these noncommunicable conditions are socially contagious.

As impressive and enjoyable as Pathogenesis is, Kennedy openly concedes that his argument is not new. Historiographically, the idea of pathogenic supremacy has had several outings, most notably in William McNeill’s Plagues and Peoples (1976), which offered a radically novel interpretation of world history through the impact of disease. A new edition in the 1980s was prompted by Aids, just as Kennedy rightly justifies the need for his book with the impact of Covid, discoveries about the microbiome and the new technologies available for recovering the pathogenic signatures of the past. What is recurrently appealing and somewhat horrifying to new audiences about this strain of history is the way it destabilises human agency to such an extent that the purpose of our endeavours is thrown into question. If the bugs write the script, what chance do we have? A microbe-centric approach tends towards biological determinism and nihilism, carrying the risk, once again, of dismissing and underfunding the social determinants of health.

Ironically, we have reached the Anthropocene, when human action is finally changing the course of our planet’s history. Emissions in the atmosphere and the misuse of antibiotics have introduced the two urgent threats of global heating and antimicrobial resistance. The pair also interact. Warmer climates invite new pathogenic dangers, as anyone who has watched the trailer for HBO’s The Last of Us will know.

Small changes can lead to massive storms, but this could also be a reason for optimism. Pathogenesis might perhaps be read as an invitation to refocus on the minute particulars of our actions, and the billions of encounters between the human and natural world that occur every day. There is an opacity and unpredictability to both evolution and history that can never be fully recovered in our accounts of either. The famous Darwinian tree of descent, which Kennedy describes, is in fact more like a wild root system. As Deleuze and Guattari wrote in 1987: ‘We no longer follow models of arborescent descent going from the least to the most differentiated, but instead a rhizome.’ These tangled interactions show that while Pathogenesis is a humbling story for humankind, it is also one of radical contingency.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in