The internet, as we all know, is a place for rage and hate. It’s a free-fire zone in which even something as apparently innocuous as Facebook – original use-case: posting family snaps for your gran – ends up incubating armed insurrection and spreading 5G conspiracy theories. But what if there was some corner of it untouched by death threats, disinformation and the baleful influence of Vladimir Putin’s troll farms? What if there was still some corner of the world wide web which lived up to its original promise of connecting people who would not otherwise be connected, and what if once connected they were nothing but agreeable to each other?

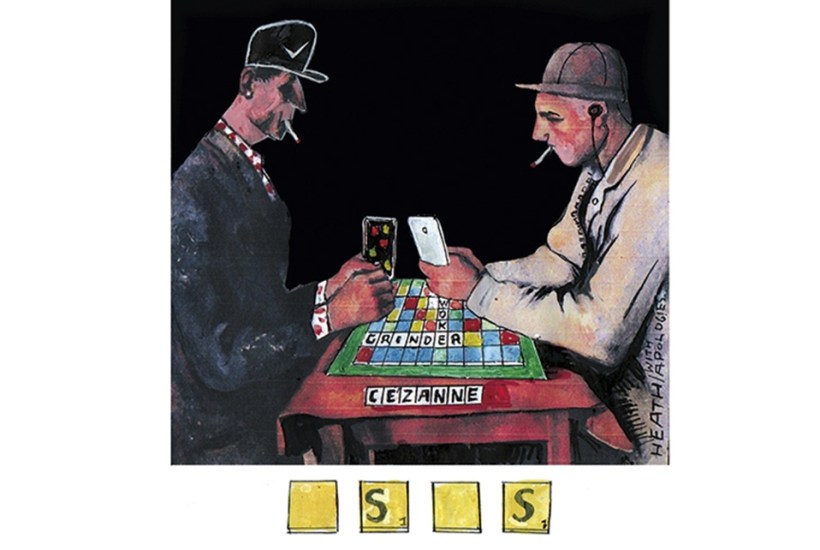

Be of good cheer. That corner exists. Not everyone is arguing with Owen Jones and India Willoughby. Not everyone is flaming Lee Anderson and Suella Braverman, fighting glowy-eyed bitcoin cultists or railing against Elon Musk. Some of us are playing Scrabble.

Playing Scrabble on a smartphone app may not change the world – not in a visible, glorious, concrete way. It may not alter the balance of power in Congress or on the battlefield in Ukraine. But, just from time to time, il faut cultiver notre jardin; and contra those who believe that screens are isolating us from one another and fraying the social fabric, here’s a way in which they are not. Little, silly games played online are considerably underappreciated contributors to the web of human interconnection and the sum of human happiness.

I have a couple of old friends whom I don’t see from one year to the next – people who live in Cornwall, or in New York, or even in the remote and inaccessible wilds of south London – but whom I keep up with simply through Scrabble.

Friendship, it seems to me, isn’t always about exchanging deep and meaningful confidences. If it were, there are a whole lot of lifelong old-school male relationships that would not even earn the name of friendship. I think of my late uncle’s Wednesday chess game, of interactions that consist only of football banter, or the silent togetherness on a riverbank of anglers. Friendship doesn’t even rely on intimacy, necessarily. It can be just about checking in: a few seconds of companionable engagement every day or two. And that’s what Scrabble, or chess – my brother-in-law thrashes me at that – offers most satisfactorily.

You will have lifelong friends with whom you have shared the deepest of emotional turmoil and whom you see in the flesh not more than once a year or so. Knowing that they are there will matter to you very much, but they are not features of your day-to-day life. But you will also have the friends with whom you have a series of games of Scrabble, or online chess, that will run over months, years or even decades – and their existence touches your life, just glancingly, nearly every day. The ebb and flow of the relationship is marked by sunglasses emojis when you get a high-scoring bingo, exploding head emojis when your opponent does, by ‘gg’ and ‘gz’. Perhaps you’ll wish one another happy birthday, or commiserate when a job interview goes badly, but that will be about it.

These two categories of friends can overlap. A game of Scrabble is more fun and less cursory, more personal and less guilt-shrouded than a Christmas card list – which you could see as the analogue method of keeping in touch with friends with whom you’ve lost touch. But they can also be quite separate. Most Scrabblers or chess players (or, I guess, devotees of play-money poker, Yah-tzee or what have you) will have acquired friends whom they never meet in the form of regular opponents. I have had a couple of pals over the year who I only knew through online Scrabble. I still smart, sometimes, at the thought of quite how comprehensively and how often ‘Mark G’ used to beat me. A colleague of mine reports that his mother not long ago attended the funeral of one of her Scrabble friends – never having met him in real life. (Turns out he was quite the fantasist – but I suppose that didn’t much matter given that the online version of him was the only version she ever knew or needed to know.)

The ad hoc online relationships which form around games are not quite a whole new thing in the world. If you were a passionate stamp-collector, or bridge-player, or Doctor Who fan, you would perhaps bump into the same people at conventions or clubs or the like. But these hobby communities have become much easier to form and much more common in the age of the internet – and they reach deeper into the lives of their participants while remaining all but invisible to the outside world. It seems to me that this is a wholly good thing – and that its effect on the mental health and general happiness of those who belong to such communities is not to be underestimated. If you live somewhere remote, or you’re lonely, or you do shift work at antisocial hours or if, like me, you work at home and seldom leave the house, these communities add up to an enriching but low-pressure form of human contact.

I play a very silly old-school multiplayer game called World of Warcraft, for instance – and so am part of an in-game ‘guild’ (you team up to kill monsters once or twice a week) whose members I interact with much more often than my real-life friends. They are scattered all over the world (I’ve become very familiar with the South Africa’s load-shedding issues) and include people of all ages and from many walks of life: grandmother, schoolboy, long-distance lorry driver, care-home worker, caterer, paediatric nurse, accountant, a couple who run a rifle range. I know them only by their in-game names or Discord tags – I could walk past any of them in the street without recognising them – yet I’m never not pleased to see them in-game. We share virtual experiences, teasing and in-jokes. They’re friends.

You don’t have to be launching a 25-man raid on Ulduar to enjoy that sort of companionship, though. All you need to be able to do is to take a minute or two out of your day to figure out how best to use that triple-letter square your opponent has left free.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in