One of the best ways to work out that somebody has not thought deeply about anti-Semitism is if they say that they wish to destroy it once and for all. When in a corner, even Jeremy Corbyn could be found saying that we must end anti-Semitism for good. Though he was of course unable to resist forever adding ‘and all other forms of prejudice’. As though such a day could ever come.

Demonstrating that it will not, last week Corbyn’s old ally and motorcycling companion Diane Abbott could be found complaining that black people have always had it worse than other groups, and that while Jews, like gingers and gypsies, might be subject to ‘prejudice’, only black people can be subjected to ‘racism’. In the ensuing storm, and while removing the whip, Keir Starmer reiterated his claim that he would ‘tear out anti-Semitism by its roots’.

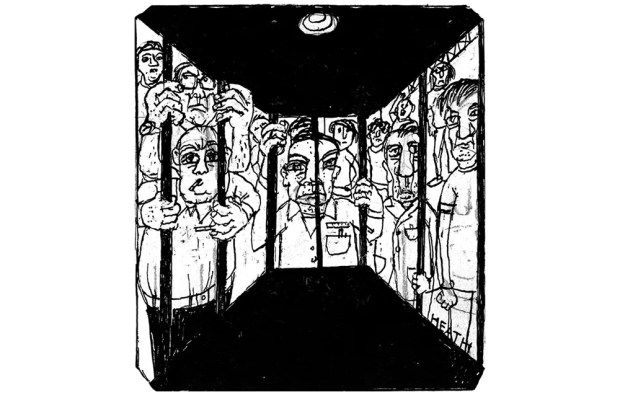

Whenever I read such a sentiment, I always wonder how people can know so little. Have they read nothing? I ask because I am afraid that it is the nature of anti-Semitism that it is ineradicable. It can be subdued, and it can be called out, but it cannot be ended ‘once and for all’. The reasons lie deeper than our age is able to consider.

Take the masterful work of Gregor von Rezzori with the slightly lurid title Memoirs of an Anti-Semite. In it, Rezzori draws a subtle but devastating portrait of attitudes towards Jews in pre-war Romania and other parts of the now long-dead Habsburg world. Perhaps the keenest insight in the book, as well as the most dramatic, is the moment when a young Romanian nobleman who has fallen for an older Jewish woman takes her out on a date and not only feels shame when his friends see them, but comes to loathe his date because she has tried to make herself look and act like everybody else. Tell me how you can eradicate a hatred that complex and deep.

Another writer, more celebrated today, addressed the same question. Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate is now recognised as one of the great novels of the 20th century. Its 900 or so pages take us through the midnight of the century, from the camp at Auschwitz to the Gulag. But one of the things that has always impressed me on a technical level about the book is that at the midpoint of the action, Grossman suddenly takes a step back. For three pages he meditates on the nature of anti-Semitism. What a thing to do in the middle of describing Stalingrad and much more.

But the more you think on it, the more this halt in the action makes sense. He says at one point in this short passage almost all that need be said about the pathology in question. Grossman writes: ‘Anti-Semitism can take many forms, from a mocking contemptuous ill-will to murderous pogroms. It can be met with in the marketplace and in the Academy of Sciences, in the soul of an old man and in the games children play in the yard. Anti-Semitism is always a means rather than an end; it is a measure of the contradictions yet to be resolved. It is a mirror for the failings of individuals, social structures and state systems. Tell me what you accuse the Jews of, I’ll tell you what you are guilty of.’

It has always been like this. So tell me exactly how you propose to ‘root out’ or ‘end for good’ a pathology which blames Jews for being poor and for being rich, for integrating and for not integrating, for being stateless and for having a state.

People who have thought about this at a facile level can be relied upon to back schemes such as Holocaust education centres and memorials almost everywhere on Earth. One reason why so many MPs back an ugly Holocaust memorial in Victoria Tower Gardens is because they imagine troops of schoolchildren being ‘educated’ about how not to hate Jews. They say that it is important to ‘learn the lessons’ of the Holocaust, as though these lessons are straightforward; as though it was almost generous of Herr Hitler to provide such a massive historical reference point for our own moral betterment.

Such people should read the most recent work of Dara Horn (author of People Love Dead Jews), who recently showed in the Atlantic how the proliferation of Holocaust education centres in America might actually be increasing anti-Semitism among the schoolchildren who are taken there. Well-meaning (generally non-Jewish) curators and guides have no time to analyse the centuries of Jew-hatred that led up to the Holocaust. Instead, the visitor is simply left with the knowledge that in the 1930s and 1940s something terrible happened. A surprising number come away with the belief that the Jews must have done something to provoke such an outrage – that they were, perhaps, disproportionately rich, for instance. What all these displays have in common is that they finish with a sort of facile generalised lesson. Don’t be mean to people. Or the question ‘Who are the Jews of today? What forms of prejudice exist in our own day that should be tackled in order not to end up with Auschwitz again?’

As Horn notes, the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington does not finish by generalising the black American experience. It does not ask whom we treat today in the fashion that American blacks were once treated. It is recognised to be an evil of its own, worthy of its own respect and historical treatment.

Not so with dead Jews. They must forever be used to improve us, available to be used by anyone wishing to make a point about – say – border security in the 21st century.

What Abbott and others consistently demonstrate is precisely what Grossman said: anti-Semitism is a mirror. We use the Jews as victims in our society because we live in a society which celebrates victimhood: victimhood without much serious suffering, of course. And we become so high on that search for victimhood that we can even forget the peoples more victimised than any other.

Tear that out.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in