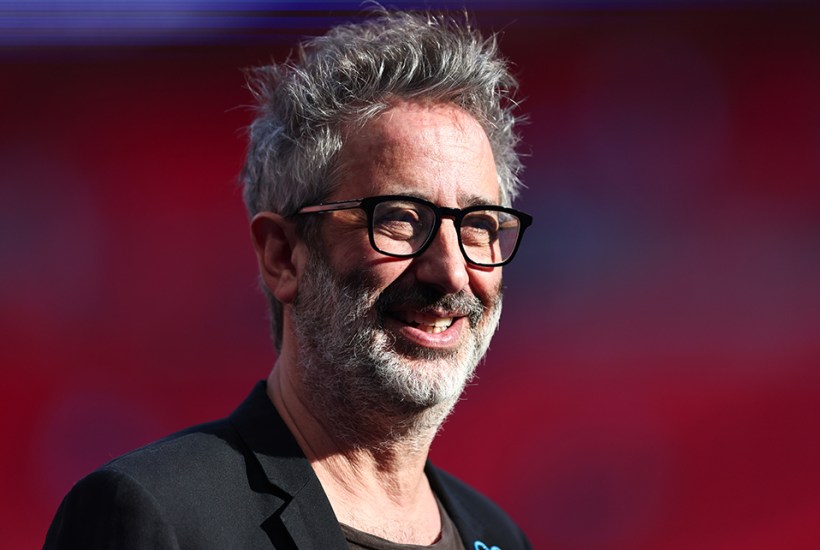

The cover design of this tract-length book associates it with David Baddiel’s excellent Jews Don’t Count (2021), which exposed a prejudice infecting both ends of the political spectrum. The God Desire resembles its precursor in other ways. Wit and dry humour abound. But as a verdict on the human appetite for the divine, it is disappointing.

The question of whether life has ultimate meaning and purpose can plainly claim to trump all others. Atheism may be a viable world view, but it is hardly unproblematic. The same goes for theism. Yet rather than building up a case to support his conclusions (work undertaken with forensic rigour on separate terrain in Jews Don’t Count), Baddiel starts by assuming the truth of unbelief before telling us that faith-based explanations of existence are rooted in a thirst for either domination or solace. A cascade of similar utterances then follows.

God was famously scorned by Nietzsche, Marx, Freud and other authors of the hermeneutics of suspicion. If you locate all fundamental urges in the will to power or economic drives or sex, then you will have little time for spirituality. But few sociologists of religion view theories as crude as these with any seriousness today. For all Baddiel’s panache, The God Desire seems trapped in a time warp. Purged of its invariably entertaining references to popular culture, the text could have been published a century or more ago.

When rare voices for the defence – John Updike, or Baddiel’s comedy partner Frank Skinner – are aired, it is only in ways that make them look idiosyncratic. Skinner is reported as following Catholic precepts on sexual morality because he is terrified of burning in hell. Wouldn’t it have been fairer to offer a more rounded account of why someone so bright returned to the church in the first place?

Commentators purporting to offer a serious take on religion should go to the trouble of investigating self-aware spiritual reflection and practice. Straw-man tactics tend to come at a price: like Richard Dawkins’s sallies in this area, The God Desire is laced with saloon-bar history and half-grasped scriptural references.

Having apparently shunned any need for solid research, Baddiel also dismisses the philosophy of religion as a matter of sixth-formish point-scoring. The late Antony Flew would have seen things very differently. After decades as one of the world’s leading academic exponents of atheism, he announced a dramatic change of mind, accepting on intellectual grounds that the universe was created. Despite his eminence, he admitted to never having studied Aristotle’s arguments for a First Cause in sufficient depth; his inferences had been further buttressed by reflections on science. Among the factors accounting for this shift are the rationality inherent in all our experience of the world, consciousness, and the implications of conceptual thought. True to the maxim that an honest enquirer should follow the argument where it leads, Flew traced his evolution in There Is a God: How the World’s Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind (2007).

There are, of course, numerous instances of principled movement in either direction across the theist-atheist divide. Though writing personally for the most part, Baddiel could have offered a snapshot of these currents. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’s ‘Indaba’ lecture on YouTube is one of the best general defences of belief in God available to an English-speaking audience. It includes an overview of the scientific literature, as well as the most potent answer I have yet heard to the question ‘Where was God at Auschwitz?’

Sacks elsewhere shows with formidable skill how meaning, mattering and the quest for transcendence – a higher dimension of reality embodying more exalted values – are discovered rather than imposed. This should at least imply that the world’s great wisdom traditions deserve a more attentive hearing than they typically receive from western opinion-formers.

Perhaps the biggest mystery about The God Desire is the frequency with which Baddiel describes himself as a reluctant unbeliever. He wishes God existed and is horrified by the prospect of total oblivion. People only practise a faith because they cling to a fantasy; the answer to the meaning of life is ‘kind of nothing’. A thin judgment, then – but also a dubious one. Far from finding this book an essay in rationality, I finished it thinking that it wasn’t rational enough. It isn’t reasonable to hold that only reason discloses the world to us. A richer interpretation will include not only the witness of our rational faculties, but also that of intuition alongside ethics and aesthetics.

Baddiel resembles the proverbial tone-deaf man standing up in a concert hall and declaring that all music is rubbish. If he’d gained a textured grasp of his subject, he might have found more grounds for hope.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in