Beirut, Lebanon

‘You can still smell it in the wind,’ says Maria. She points out from the neon-lit bar along Beirut’s shorefront to the dark port area just across the road, where tangled metal and broken concrete jut out into the sky.

Maria had been working from home on August 4, 2020, when 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate left to rot in a warehouse on the harbour suddenly detonated, killing more than 200 people and levelling much of the Lebanese capital. Her usual daily drive back from her job as a reporter on a local newspaper – since shuttered due to lack of funding – took her along the seafront. Had she gone into the office that day, she’s convinced she would have died.

‘If there’s a problem in Lebanon, the answer is always corruption’

‘It’s a burning smell – like plastic. One day we’ll find out that it has been poisoning everyone here this whole time, giving us all cancer.’

Like most young Lebanese people, 26-year-old Maria grew up in one of the most stable countries in the Middle East. The brutal 15-year sectarian civil war that pitted the country’s Christians and Muslims against each other, and saw Israeli troops invade the neighbouring nation, ended in 1990, half a decade before she was born. The scars of the fighting still dot downtown Beirut, with the burned-out shell of the Holiday Inn, once used as a snipers’ nest, towering above the city centre, the walls pockmarked by artillery fire.

Around it though, high-rise office buildings, luxury apartment blocks and even a giant honeycomb department store designed by Zaha Hadid had sprung up. Fuelled by foreign investment and a banking sector that profited from helping the Iranian regime avoid international sanctions, Beirut quickly became the region’s most exciting economy.

A power-sharing agreement had ended the civil war and brought stability. Quotas were set for politicians from each of the main ethnic groups that call the country home. The President, by law, must be a Maronite Christian, the Prime Minister a Sunni Muslim and the Speaker of the parliament a Shia. Others, like Armenians, Protestants, Alawites and Druze, have a set number of seats guaranteed in parliament. Voters are just left to choose who they want to fill the seats. For years, the deal guaranteed an uneasy peace that allowed people to get on with rebuilding their lives.

Now though, working-class neighbourhoods near the port are strewn with rubble and the apartment buildings are empty – the residents either died in the blast or simply packed up their things and left. A collapsed petrol station is taped off from the pavement, still undisturbed after almost three years.

The glass and steel tower residential towers of the financial district, however, have been fixed up and private security guards armed with Kalashnikovs patrol the barbed wire barricades, protecting the homes of politicians, bankers and business leaders.

‘They’re all crooks,’ says Khaled, a middle-aged former pharmacist who now drives a taxi on the streets of Beirut. ‘There’s no Christians or Muslims anymore – just ordinary people and politicians who steal from us. We don’t have a government.’

Almost every day, he hands over a thick stack of cash, about the size of a paperback novel, for a tank of petrol. According to the government, one US dollar is worth 15,000 Lebanese pounds. But, in reality, black market exchange rates – operating everywhere from street corners to upmarket hotels – value the currency at almost 80,000 pounds to the dollar.

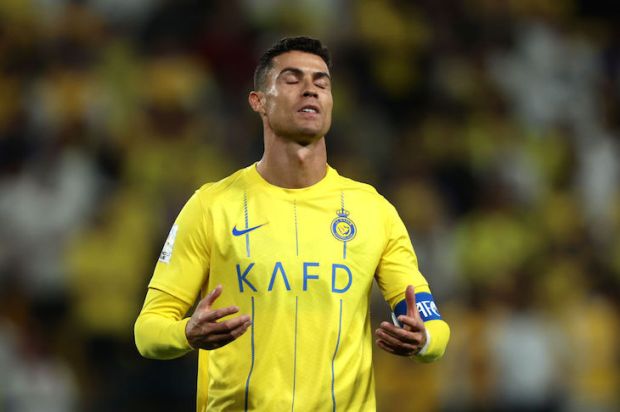

(Photo: Getty)

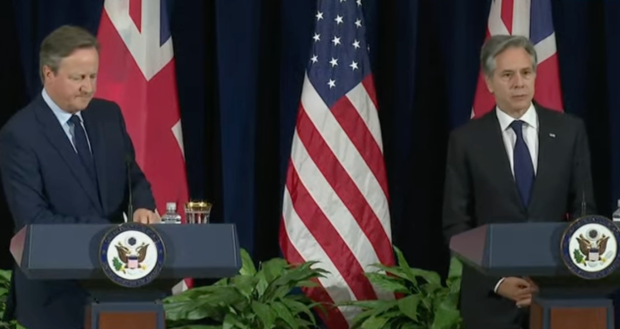

(Photo: Getty)

Lebanon’s largest note, the 100,000 bill, used to be a precious symbol of wealth. Now ordinary people carry around bags full of the near-worthless denomination just to pay for their groceries. Smaller notes can be found scattered around with the trash that lines the streets, swept by the wind into empty building sites.

According to the World Bank, Lebanon’s economy is a ‘Ponzi scheme’ that for years served as a tool for the ‘systematic capture of the country’s resources.’ It has now well and truly collapsed. Banks, owned by wealthy elites, issued preferential loans to politicians and favoured businesses for them to build massive state infrastructure projects. The money vanished and the construction was never finished.

As a result, while people’s accounts may say they have plenty of funds, the banks simply don’t have their cash anymore – they are only able to withdraw tiny sums at the official rate. With inflation at 123 per cent and the government insisting everything is fine, people’s life savings have gone up in smoke. Even basic goods in the supermarkets are far more expensive than people can afford and families are forced to decide what they can cut from their budgets.

One Armenian businessman who had built an empire importing parts for construction vehicles and heavy machinery says he has been forced to take on a side job, unable to access millions of dollars that the bank insists is still in his account. Others forlornly check their balance at ATMs on the street, holding out hope they may see their earnings again one day. Cash is king in a country where using a debit card means paying four times more than you should. Half a dozen cases of desperate people holding up local bank branches and demanding their own money – sometimes to pay for a loved one’s medical treatment – make the news regularly, and even high street banks are now fortified like military outposts.

It’s not the only area in which the state has failed. Providing electricity has been left up to local officials and, through corruption, incompetence or a mixture of both, is entirely unreliable. Locals joke that their lives are dictated by the private energy contractors they pay for on top of their taxes, with the power schedule determining when they can shower, cook and take the elevator up to their high-rise apartments. Businesses like cafes and restaurants have invested in generators, but it’s not unusual for the lights to cut out during busy times.

‘If there’s a problem in Lebanon, the answer is always corruption,’ says Maria. ‘No money? Corruption. No electricity? Corruption. Why don’t we have buses or public transport? Why did hundreds of people die in the port blast? The answer is always the same.’

But the complex power-sharing system that was designed to prevent sectarian violence can’t easily be undone. Fearing other ethnic groups might take charge if they let their guard down, each sect votes in the same influential elites who are responsible for causing the crisis. None have ever been prosecuted for turning the entire country’s economy into a piggy bank for politicians and wealthy businessmen, and those responsible work behind a ring of steel in the centre of Beirut, protected by the army and insulated from the consequences of a system they built for themselves. In private, Christian and Muslim community leaders do deals and carve up the country they purport to lead.

Likewise, the inquiry into what caused the port blast almost three years ago is deadlocked, with those running the country refusing to face scrutiny. In January, the sidelined judge tasked with overseeing the probe suddenly indicted the country’s own prosecutor, Ghassan Oueida, as well as intelligence chiefs and a number of other top officials. In revenge, Oueida ordered the release of all of the suspects in the case – mostly port workers who had been accused of negligence. Many are since believed to have fled abroad. Justice, it seems, comes second to protecting the elite.

‘What is there left to do,’ asks Khaled, the pharmacist turned taxi driver, ‘except try and survive, and maybe move away? Lebanon isn’t a country anymore. It’s a scam – and we are the ones paying.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in