According to the census, there are more Christians in the UK than there are atheists and agnostics – yet the churches are empty. These Christians, it seems, don’t take their faith too seriously. Nor, I fear, does Nicholas Spencer, who has written a big book arguing that science and religion are fundamentally compatible. He’s wrong; but, surprisingly, he is more wrong about religion than he is about science.

Let me start by laying my cards on the table. I’m the son of a missionary. My father’s parents were atheists and scientists. He, in adolescent rebellion, became a Christian; I, ditto, became an atheist. Because I was raised abroad I barely knew my paternal grandparents, but I inherited from them one thing: a copy of Fred Hoyle’s The Nature of the Universe (1950), in which Hoyle attacked the ‘big bang’ theory that the universe had originated in a moment of creation and argued that it had always been exactly what it is now. Hoyle was convinced there was a fundamental conflict between science and religion, and I was thrilled to find a door which opened into a world without faith. Unfortunately, Hoyle’s science was wrong: the universe really did originate in a big bang. Indeed, Hoyle had a remarkable propensity for being wrong. He believed life on Earth was, and continues to be, seeded from outer space. But he was perfectly right that religion and science are at odds.

Spencer doesn’t agree. We ought to accept, he argues, that Hoyle’s steady state theory was perfectly compatible with monotheism, and that the big bang is no proof of the existence of a creator God. When religion and science seem to be at odds it is because one side or the other is claiming too much and conceding too little. Both William Paley, whose Natural Theology (1802) argued that nature demonstrated the existence of a designer, and Hoyle, were equally at fault.

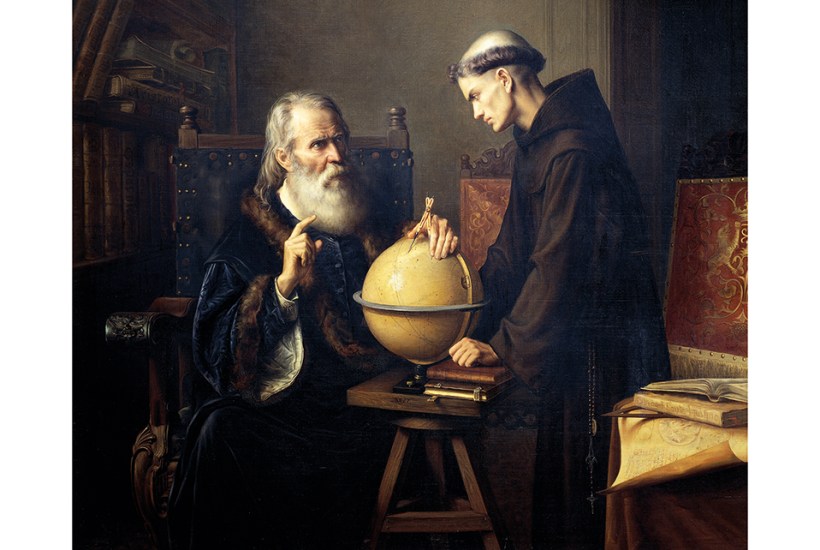

Spencer is remarkably good on the history of science. He writes intelligently about Galileo, Newton and Darwin. Admittedly, he doubts that anyone was really disturbed by Galileo’s discoveries, and there he is surely wrong. Galileo himself was no Christian, although he was obliged to pretend to believe. Descartes, grasping the significance of Galileo’s discoveries, correctly saw that the sun was just one of an indefinite number of stars, and concluded that the universe had not been made to provide a home for man. Pascal wrote: ‘The silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me.’ After Galileo, human beings for the first time seemed insignificant; in Voltaire’s Candide we are likened to rats who have stowed away on a ship. But Spencer is basically right: Descartes and Pascal saw no need to abandon religious faith just because the Earth was no longer at the centre of the universe; and if life on Earth was only an insignificant part of some larger plan, that did not mean there was no plan. Even Voltaire claimed to believe in a God.

Spencer is thus – up to a point – an advocate of what Steven J. Gould called NOMA: there is No Overlap between the MAgisteria, the authority fields, of science and religion. This is, of course, a profoundly ahistorical argument – for the three monotheistical religions have always claimed that the creation of the universe out of nothing was a real event, not a fiction. NOMA is a modern invention. We can’t read it backward into the past.

Spencer, however, is not really a NOMAtist. For he holds that when it comes to human nature, religion does find itself at odds with certain possible scientific claims. From La Mettrie’s Man a Machine in the 18th century to E.O. Wilson’s sociobiology or Daniel Dennett’s contemporary physicalism, hardline materialism is, Spencer argues, incompatible with religion. Humans are, he claims, ‘spiritual’ as well as ‘material’, concerned with ‘things like meaning, significance, transcendence, purpose, destiny, eternity and love which have always been the building blocks of a religious understanding of reality’, and thus humans can’t be mere machines, and machines will never become human. Chatbots may tell jokes, but they will never have a sense of humour; they may express sympathy, but they will never feel your pain.

Leaving aside the fact that Spenser’s spiritual concerns are what Dennett calls ‘deepities’, words that mean less than they seem, there’s no acknowledgment here of the Christian belief in sin, redemption, incarnation and salvation, of heaven and hell. Of course if you reduce religion to some sort of Spinozist pantheism or Voltairian deism you can smuggle in the spiritual alongside the material while generating only minor, localised conflicts between religion and science. But Judaism, Christianity and Islam have always been at odds with pantheism, and indeed with deism, for the simple reason that they are not merely monotheisms, but also religions of revealed truth, and religions which declare that God has been active in history – revealing his truth being only one of his activities. My father committed himself to what we must now call the missionary practicum not because he cared about meaning or significance in some sort of abstract way but because he really did believe that Christ had risen from the dead and that doubting Thomas had touched His wounds. He had his doubts about eternal damnation, but none about life after death.

This raises a further problem: the disappearance of Enlightenment irreligion from Spencer’s story. Arguing that science and religion are not necessarily in conflict, Spenser sidesteps an obvious follow-up question: what did undermine faith, if it wasn’t science? Where the pagan philosophers believed matter had existed from eternity, even if design had not, monotheism introduced not only a creator God, but a unique claim to historical truth. The great assault on Christian faith came not from science, not from a denial of creation, but from history. Spinoza, Richard Simon and Voltaire maintained that Moses could not have been the author of the Pentateuch, which could be discarded as an unreliable historical source. Bolder still, Diderot and Hume argued that the odds against a miracle taking place were so high that no human testimony could make it rational to believe in such events. It was much more plausible to presume the supposed witnesses were mistaken, corrupt, or imaginary than to take seriously the claim that Lazarus (or indeed Christ) had risen. Christian faith depended on ignoring such arguments. My father’s religion was grounded in Frank Morison’s Who Moved the Stone (1930, and still in print), a work which assumed that the sort of evidence which might be adduced in an Agatha Christie whodunit was more than adequate to prove that Christ was risen.

But this doesn’t quite explain why miracles ceased, for so many 18th-century intellectuals, to be credible. Belief in magic, in witchcraft and in miracles fell away because it simply came to seem obvious that there was no space for supernatural events within the natural world. Nature, said Galileo, is ‘inexorable and immutable’. This conviction isn’t really a scientific one but rather a meta-scientific one, and it is this meta-scientific belief, rather than any particular scientific theory, which is destructive of religious faith as it is understood by the monotheistic religions. If there is (as the NOMAtist would claim) no conflict between science and religion, there is an inescapable conflict between belief in a God who is active in the world and the belief everything that happens is explicable according to the workings of an inexorable nature.

So this is a profoundly puzzling book. Spencer knows his history of science. He recounts the set pieces of any such story – the trial of Galileo, Huxley vs Wilberforce, the Scopes monkey trial – with bravura. He has a good grasp of how science has changed over time, and he also understands that the word ‘religion’ meant very different things to Cicero, Augustine and the author of The Golden Bough. But he doesn’t seem to grasp that the pared down, purely ‘spiritual’ religion he defends has virtually nothing in common with that of Augustine, Calvin, Loyola and Newman.

What this book marks, in fact, is the quiet triumph of meta-science over faith, for faith in the Bible as history, in the great eschatological drama of redemption, has been replaced here by faith, not in a creator and redeemer God, but in the peculiar specialness of human beings. Perhaps we are special; but there’s more to religion than an insistence that, because we make our lives meaningful, the universe must have a meaning. Though Spencer finds the idea repugnant, maybe we are just peculiar machines whose functioning depends on producing, in endless succession, deepity after deepity. If there is one thing that is clear about human beings, after all, it is that we have a remark-able talent for self-deception – and what is religion but a trick we play on ourselves?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in