As the Dutch farmers’ electoral success showed, some voters are waking up to the fact that their rulers don’t have their best interests at heart. Indeed, they may not have their voters’ interests at heart at all, let alone their best interests.

This insight was beautifully argued recently by an anonymous German academic who goes by the name of Eugyppius. The pandemic has not received due credit for surfacing (and retiring) a new raft of pundits, and Eugyppius’ fresh, clever Substack feed, A Plague Chronicle, has rightly come to prominence. He rejects the Covid conspiracy theory that elitists such as Bill Gates want to depopulate the planet, and instead blames pandemic tyrannies and stupidities on the growth of an extreme universalist philosophy, in which caring for far-off abstracts such as the planet, all mammals, living things and even aliens and rocks, is more important than caring for family, friends and country.

His evidence is drawn from a 2019 Nature study, authored by leading US social researcher Jonathan Haidt among others, which found that conservatives cared most of all about immediate and extended family, friends and country. This would be the norm. People have traditionally fought and died for their kith and kin, but not so much for the planet, furry animals and little green men.

By contrast, universalists, or ‘liberals’ in the US sense, said they cared little about family and friends. They cared most of all about ‘all animals in the universe, including alien lifeforms, all living things… including plants and trees, all natural things… including inert entities such as rocks’. Universalists love ideas, not specific people, and the data was clear and dramatic; universalists begin caring where parochialists or conservatives stop. These professed beliefs may not drive actual behaviour, but it’s a strong and shared default position.

‘Once you have seen this simple dynamic at work, you cannot unsee it,’ Eugyppius writes. When the cascade of US banking collapses occurred in the last fortnight, we discovered that now-failed Silicon Valley Bank emphasised diversity and inclusion policies above such mundane banking concerns as having a chief risk manager, while Signature Bank released dancing and singing bankers in music videos. Some people cannot walk and chew gum at the same time, and keeping banking standards rigorous was plainly a lower priority for these managers than peer group approval. Universalist beliefs also explain the prioritising of the rights of tiny minority groups such as transsexuals above the rights of sportswomen, girls in locker-rooms and young children, who are everyday people and so not worthy of one’s lofty, if abstract, concern. And even as our society is inundated with excessive and annoying ‘welcome to countries’, no solutions have been found for ill-health, poverty and domestic violence in Indigenous communities.

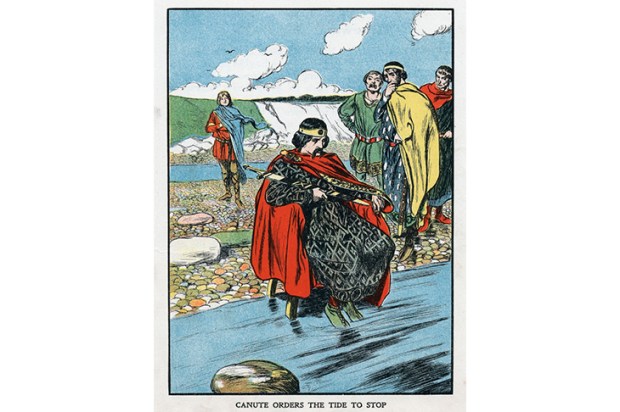

The argument will be that they do care, of course, that they’re saving you from yourself, even as they’re turning off reliable cheap energy for pensioners, and upending society to enact an entire climate change agenda that will make your steak dinners, petrol cars and gas stoves illegal and unaffordable. It’s just that they don’t care now, about you and what you want. They care about what they want, which means that it may help someone or something in 100 years’ time (although that’s doubtful). Nor does the failure of the climate to boil or freeze disturb the zealots; there’s such sanctimonious pleasure in pretending to care about aliens, rocks and small furry animals rather than the smelly or sweet little old lady next door.

Human beings are warts’n’all, and harder to love with zealous, chest-beating intensity than beautiful ideas. Political philosphers, from Marx to Nietzsche to Schopenhauer and Sartre, famously mistreated those around them, proving that high thinking is no guarantee of high conduct. Romantic fantasies about nature are rarely held by farmers and country folk, but by inner-city elites whose insularity protects them from the reality-inducing stings of close contact. They will never be endangered by snakes, or have to kill animals for a meal. The reality of inborn sexual differences can be ignored by the childless but not by parents. We now have swathes of highly placed elites who care more for some abstract notion such as carbon emissions, than they do for their communities, whom they see as the problem. And they are now so affluent and protected that reality can be kept at bay seemingly indefinitely.

This problem is no less real, for the elites’ unawareness of it. We imagine we know what’s right, when history proves relentlessly that we have little or no idea. Many people can’t decide what’s best for themselves in the moment, much less make good judgments on how other people should live. The further away one gets from a problem, the less likely one is to understand its dimensions. How then can elites, especially those in remote transnational bodies, know what’s best to do for family, friends, acquaintances, different nations, the universe?

Ex-leftist UK journalist David Goodhart, he who invented the terms ‘somewheres’ and ‘anywheres’, tells an anecdote about a top civil servant who confessed to driving controversial UK immigration decisions based not on what was best for Britain, but what he thought was best for Europe and the world. Never mind that it’s hard enough to work out what might be good for a nation, but to imagine one can make wise judgments for such wider groups is arrogance of a breathtaking order. No doubt similarly high-minded and persuaded Sri Lankan bureaucrats felt it would be great for Sri Lankan farmers to abandon chemical fertilisers.

The solution of course is elections, when voters can smack around their leaders and return reality to the mix. Bad luck for the West, led by a US leadership increasingly run by a universalist Washington bureaucracy which can manipulate the country’s gobsmackingly poor and fraud-prone electoral system to cock a snoot at the voters. Eugyppius concludes change will only come when conditions worsen sufficiently; how much is ‘the terrifying question’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.