Why did nobody see it coming? When the late Queen asked this question about the crash of 2008, on a visit to a London business school, no one had a clear answer. Why, in a financial world crawling with regulators, did no one spot that subprime mortgages were toxic, on the brink of falling apart? The simple answer is that we got too comfortable. We assumed that times had changed and dropped our guard.

It looks as if we’ve dropped our guard again. On the way out of the financial crash, we seem to have simply and blindly assumed another set of false beliefs: that ultra-low interest rates, designed to help tackle recession, were here to stay. Entire business models were built on this premise. But then inflation returned – and interest rates shot up. And now we begin to discover just how many banks, pension funds and other companies have bet the house on the idea that rates would never really rise again.

Despite being the 16th largest bank in America, Silicon Valley Bank was exempted from many stress-testing regulation that others were compelled to follow. It did its best to show it was one of the good guys: last year, it publicly committed $5 billion in ‘sustainable finance and carbon neutral operations to support a healthier planet’. But how sustainable were the bank’s own finances? It turns out its business model was hugely sensitive to interest rate hikes. It had tied up its money in government bonds, which lower in value as rates rise. SVB did have some insurance against this risk – yet despite rates rising, decided to drop it last year.

Compounding the problem was that SVB’s client base included a lot of tech companies, which are themselves more vulnerable to rate rises because so much of their value is based on the promise of profit in the future. So much nervousness created a run on the bank, which eventually led to its collapse. So here we are, back again at the Queen’s question: why did no one see it coming? Why, in this case, was SVB so complacent in the year leading up to its crisis, when inflation was soaring in the wider world? And what other problems are we about to discover as interest rates approach historical averages once again?

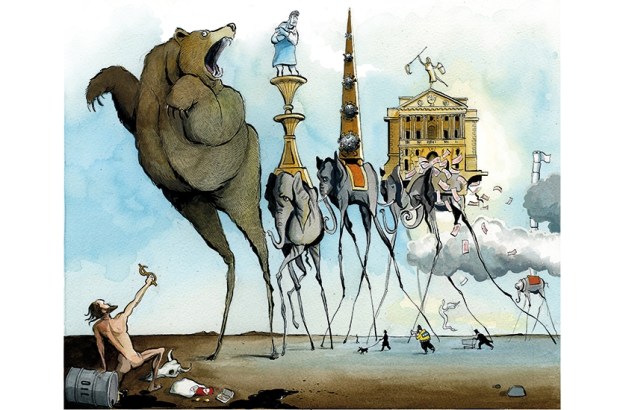

The world over, inflation is back – and interest rates have been playing catch-up to tame it. In the US rates have shot from 0.25 per cent to 4.75 per cent. In the eurozone, from -0.5 per cent to 2.5 per cent. In Britain, they rose from 0.1 per cent to 4 per cent. This affects everyone: homeowners, companies, governments, and certainly Silicon Valley.

There’s an old saying on Wall Street: interest rates will keep rising until something breaks. Breaking point may now have arrived in America (two other regional banks have also collapsed). But the United Kingdom itself was very nearly another casualty last year, when the prospect of soaring rates triggered a pensions crisis that nearly crushed the government.

It wasn’t a bank that time, but liability-driven investments (LDIs), a derivatives-based investment used by pension funds. Seen as virtually risk-free and linked to UK government debt, regulators encouraged them so much that their value quadrupled to £1.6 trillion over a decade. If the bubble burst, it would take the UK economy with it.

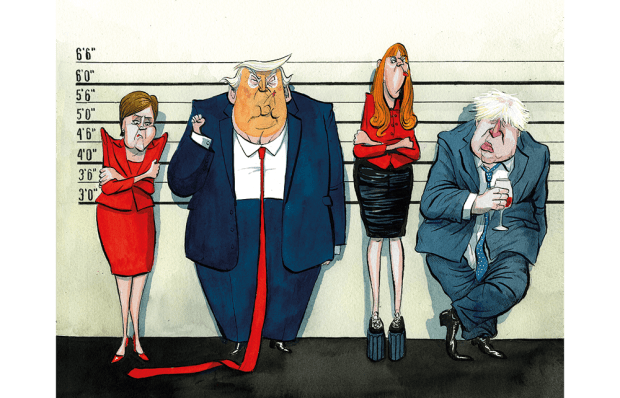

It suits many political narratives – and particularly the government’s – to blame every bit of last year’s market mayhem on Liz Truss. The former prime minister has become a shield, a way of deflecting criticism of the current trajectory. Any calls to halt corporation tax rises in this week’s Budget or to address household tax burdens were met with a warning: tax cuts are dangerous, remember what happened only six months ago.

It’s an easy narrative because Truss made a series of political miscalculations for which it is impossible to pass the blame. She breezily rejected what she viewed as ‘Treasury orthodoxy’ opinions and went so far as to remove people from their posts who might have stood in the way of her tax plans. But even if she had sought out every opinion from the Treasury and the Bank, she still would not have been properly aware of how dangerous the economic situation was – of the LDI landmine that lay under the UK economy.

Why not? Because no one seemed to know about the risks. LDIs are not some unregulated, rogue investment. In the lead-up to the crisis, they were both regulated and collectively assessed, and authorities assumed their calculations showed that everything was under control. But those calculations, as revealed by the House of Lords report into the crisis last month, contained a regulatory blind spot. The funds had been assessed as able to handle a rate rise of one percentage point (a big rise when rates are virtually zero), while a faster and sharper rise was considered to be, in the words of the pensions regulator, ‘outside the realms of plausibility’.

Truss knew that her plan – deficit-financed tax cuts – risked pushing interest rates higher. In fact, that was a core part of the strategy, to balance out looser fiscal policy with tighter monetary policy. It was a risky move, even based on what was known at the time, given the abysmal state of the public finances. But no one, inside or outside government, had properly flagged that LDIs had left pension funds – and billions of British savings – at the mercy of rates. In the end, it took the promise of a £65 billion facility from the Bank of England to stabilise them.

So what else don’t we know? What other landmines have years of distorted economic activity and record peacetime spending planted? The furlough scheme and pandemicsupport measures always ran the risk of prolonging the life of unviable companies. Before the pandemic, corporate insolvencies ran between 15,000 and 20,000 a year. But in the first year of furlough, this dropped to 11,600. Companies that would have gone bust without taxpayer money managed to stagger on. Accepting this was the trade-off for making sure viable companies could continue to exist after lockdown.

As the furlough scheme was extended over and over again, worry crept into the Treasury. The then chancellor Rishi Sunak’s fiscal hawkishness led him to question what these ‘zombie companies’ – dependent on cheap loans, generating just enough cash to continue operating but not to invest in growth – meant for the future of UK business. Having companies collapse is part of the process of economic renewal, which gets the economy growing and helps people move to better-paid jobs.

This was always Sunak’s fear: that the legacy of the pandemic policy might stifle economic recovery, and that the orthodoxy around tame inflation and low interest rates would prove to be wishful groupthink.

In March 2021, Sunak prepared the public finances for an interest rate hike of 1 per cent – and was criticised by virtually every-one for needless panic. Two years on, the UK’s base rate sits at 4 per cent. No one thinks the effects have been fully felt across the economy yet; no one is prepared for what will happen if rates rise further.

The UK economy is still smaller than it was pre-pandemic, but even the countries that have recovered are looking down the barrel of interest rate rises. Whispers of a global debt crisis are passing between economists who only a few years ago would have insisted there was nothing to worry about.

But the most worrying concerns will be lurking just beneath the surface. Lord Hollick, who chaired the investigation into the LDI crisis, summed up what we could be facing: ‘If these problems aren’t taken seriously and looked at, you run the risk that something like that will happen again. And that’s not a good place to be.’

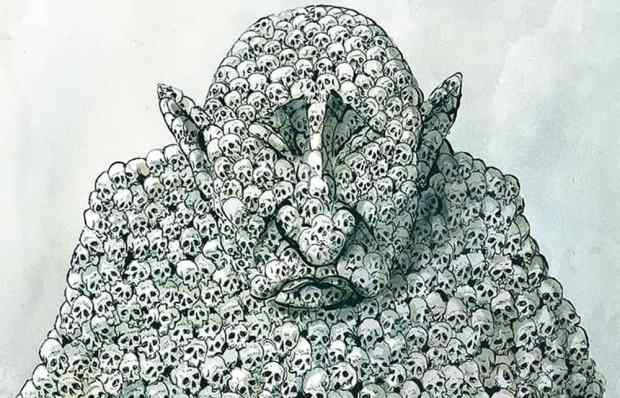

Botched pensions investments and Silicon Valley’s banking failure may only be the start of our problems. The decade-long denial that interest rates might rise makes it even more likely that the next crisis is yet to show itself – still undetected, still building.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in