‘Asia is one’, wrote Okakura Kakuzo, the Japanese art historian, at the start of his The Ideals of the East in 1901. Nile Green disagrees in this sparky and impressive book. There is no reason why ‘Buddhism, Confucianism or Shinto should be more intelligible to a “fellow Asian” from the Middle East or India than to a European’. For one thing, ‘Asia’ is home to a vast number of language groups, including ‘Sino-Tibetan and Turkic, Indo-European and Semitic, Dravidian and Japonic, Austroasiatic, and others’, as well as ‘to a far wider variety of writing systems than Europe, Africa and the Americas combined’. So how and why, then, did the clumsy label come into being and stick?

The blame, argues Green, lies with Europeans. Ancient European geographers had grouped large numbers of people together as ‘Asians’, leading to the formulation of a ‘European idea of Asia’ that came to be widely adopted – not least by ‘cultures that had for centuries cultivated their own conceptions of geography’. One greatly overlooked outcome of the rise of global European empires was a set of more intense interactions with Europe – something that Green sets out to correct by ‘looking at printed books and magazines in Urdu, Persian, Arabic, Gujarati, Ottoman, and occasionally Bengali, Japanese, Burmese, and other languages’ to reconstruct ‘what the broader reading public knew – or at least potentially knew – about other parts of Asia’.

Green also pays attention to maps and textbooks translated from English, of which Clift’s First Geography (published in Bengali, Urdu and Tamil) was a classic example, which established and then cemented preconceptions about different regions in Asia to create ideas of homogeneity that bore little resemblance to the complexities and diversities of reality.

Rather than being a home to peoples who were connected through extensive exchange networks, says Green, interactions between different parts of Asia were highly localised, and characterised by levels of contact that were somewhere between low and non-existent. What changed this model were the ‘infrastructures of European empires that brought the peoples of Asia into closer interaction than ever before’ – above all in the 19th century. One reason for this was language: ‘Inter-Asian inter-actions were all based on common knowledge of English rather than any shared Asian language’, something which, of course, has its own ironies when set against a backdrop of the role that Europeans apparently had in developing the idea of ‘Asia’ in the first place.

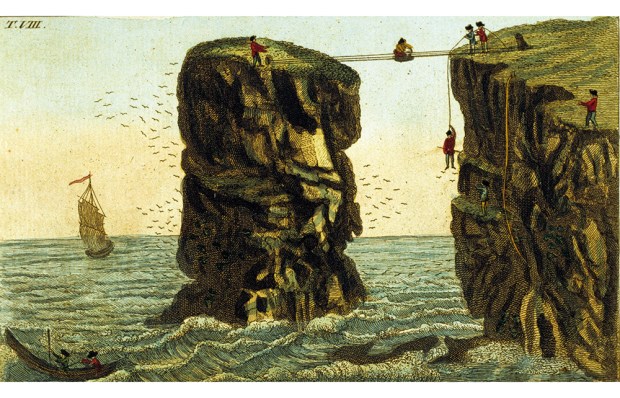

New technologies played a role in bringing regions into closer contact with each other. The web of port cities was part of this story. But most important of all was the development of printing centres. As Green shows, the ability to print and disseminate texts was a central plank in the intellectual efflorescence that saw hives of activity spring up from Persia to Burma and from Bengal to Japan. They awakened interest in the past and the present, and not only shaped ideas about identities but spurred competition that could be intense.

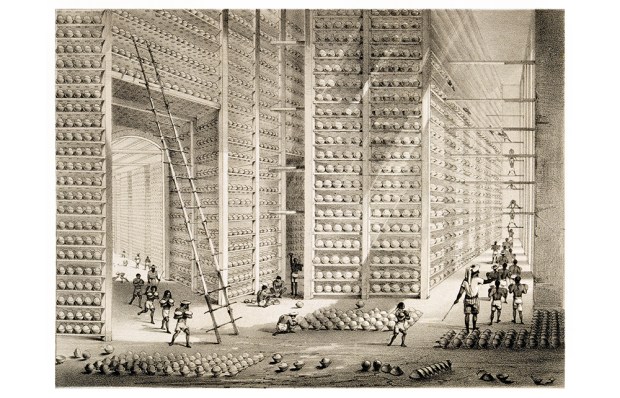

Administrative demands lay behind some of the need to create ‘teaching materials, law manuals and other texts’ in the wake of the Battle of Plassey in 1757 – the seminal moment that laid the basis for the East India Company’s rule over much of what is now India. But missionaries were hot on their heels, determined to print works that could help evangelise the masses. That did not always go down well with the East India Company, which tried to limit and even ban missionaries from its territories because of concerns that preaching against their profit-driven business model might impact the bottom line.

Books and leaflets were churned out in places such as Serampore, a few miles upriver from Calcutta, or Moulmein in Burma – which produced more than four million pages of text between April 1830 and December 1832, or, later, the Methodist Press in Lucknow that was printing vast quantities of material every year in English, Urdu and Hindi by the late 1870s. Some played fast and loose with the truth. Among the most notorious was a Russian chancer named Nikolai Notovich, who claimed to have found a manuscript in Ladakh that proved that Jesus had studied in India before returning to the Holy Land – something that was in turn embroidered by others to assert that Jesus had not been buried in Jerusalem but in Kashmir. This was part of intense and often angry spiritual competition which the British authorities sought to monitor and control through censorship and even through bans.

Many polemics poured scorn on other belief systems, including Hinduism and Islam, which were routinely compared negatively to Christianity. This in turn generated responses, defences and refutations, such as those written by Jawad ibn Sabat, or in some cases even led to decisions by the state authorities to found printing presses – as was the case in the Ottoman empire and in Persia in 1817, where widescale distribution of copies of the New Testament in translation stoked fears that waves of conversion would follow.

Others followed suit. Buddhists in Ceylon wrote tracts against Christian critics; Baha’i missionaries claimed that their beliefs reflected the fulfilment of Islamic prophecies, which in turn generated furious denunciations from critics such as Rashid Rida in the pages of his journal al-Manar. Some, like the Parsis – adherents of Zoroastrianism – living in Bombay, Calcutta and Rangoon, went the other way, actively working to prevent conversion, partly to halt the never-ending draws on their famous acts of charity.

One outcome, though, was what Green calls the ‘rediscovery of Buddhism’ and the ‘Indian intellectual engagement with Buddhism… after a silence of many centuries’. This, too, was not straightforward, with Vivekananda – perhaps the most famous Indian philosopher of the 19th century (at least in Europe) – hardening in his views about the shortcomings of Buddhist beliefs and of the Buddha in particular.

Yet for many in ‘Asia’, Buddhism, like Islam, provided common cultural and religious bonds that went back centuries – millennia even – to a time before the arrival of Europeans. Contrary to Green’s argument, Nehru said in 1947 that far from serving to connect people and sparking searches for identity and diversity, ‘One of the consequences of the European domination of Asia has been the isolation of the countries of Asia from one another.’ With the age of European empires drawing to a close, he went on, ‘a change is coming over the scene now, and Asia is again finding herself’.

Perhaps not surprisingly, I would disagree with Green’s summary dismissals of connections that brought Islam from the Hejaz to India and to South East Asia, of Buddhism spreading into Central Asia and China two millennia ago, of the schools of scholars under the Abbasids or the Tang that translated a wide range of texts by Indian scholars into Arabic and Chinese respectively, and of the vast zones of cultural exchange that created what scholars today often call the ‘Persianate world’ and the ‘Sinosphere’ (both of which, like ‘Asia’, are as problematic as one wants them to be).

I am not completely convinced either that ‘Europeans’ are to blame for the idea of Asia as a uniform landmass, filled with people who were ‘Asian’. For one thing, almost all ‘ancient European geographers’ (such as the Greeks, who might have been surprised to be called Europeans) stressed the diversity of people in Asia, which was a place they usually took to mean ‘the East’. Indeed, even Herodotus had said that the name and the concept of Asia was a ridiculous simplification that obscured diversities and continuities. It was certainly true that the age of European empires was one of prejudice, bias and racial triumphalism – and not only in Asia. But while Europeans (rightly and understandably) attract the most attention from modern scholars, there were plenty of other colonial powers on the move too, not least the Qing, the Qajar, the Japanese and the Siamese, all of whom had their own ideas about race, identity and conformity that simplified and projected power, and denied rights that mirrored those of other empire builders farther away.

For another thing, of course, the idea of ‘Europe’ and Europeans is just as woolly, vague and misleading as that of ‘Asia’: while (some) British, French, Dutch and others might well have been cultural and intellectual imperialists in Asia, the same cannot be said of Czechs, Poles, Bulgarians or all ‘Europeans’, who are lumped together as sharing intangible responsibility for the prejudices of global empires.

As Nehru’s comment shows (and likewise those of people across ‘Asia’ who found Japan’s victory against Russia in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-5 thrilling as a statement that colonialism could be resisted), emphasising common bonds for political expediency was, and is, how names and labels get used. As Green rightly notes, crude designations for continents and cultures are simplistic, and betray the prejudices of those that use them. What is ‘Africa’ after all, or ‘South America’? What is a liberal? Or even in today’s world for some, what is a man or a woman?

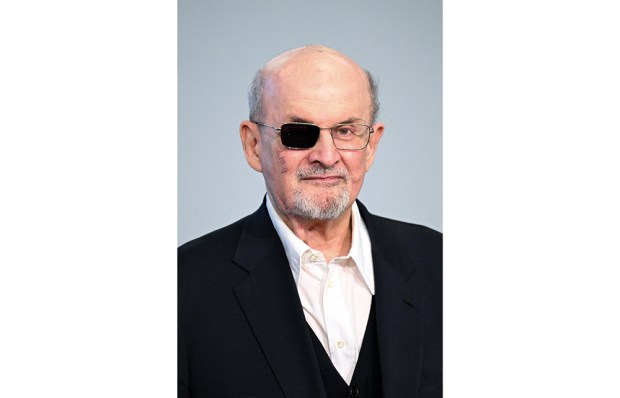

Nevertheless, Green’s book is a tour de force. He is a formidable scholar, in command of a vast array of material from Iran, India, China and Japan. The question he asks – what is Asia, and on whose terms? – is thrilling, invigorating and important, not least if one is to believe many commentators that we are already living in the ‘Asian century’. It might just be worth asking what that is, where and why. Green offers an excellent place to start.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in