Edinburgh

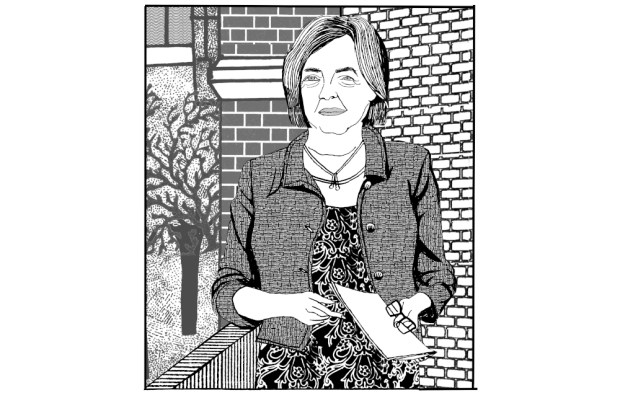

What did Kate Forbes’s supporters expect would happen? When the Scot-tish finance secretary and Scottish National party leadership candidate was asked whether she would have voted for the legalisation of gay marriage if she had been in the Scottish parliament at the time, she said that she wouldn’t, because as a devout Christian she believes marriage is between a man and a woman. She added that if she became first min-ister, she would not ‘row back on rights that already exist’.

In response to her honest answer, several of her backers threw their hands up in horror and withdrew their support. One of her own finance ministers said he was ‘unable to continue to support Kate’s campaign’ because equal marriage was one of Holyrood’s ‘greatest achievements’. Others followed suit, all sounding surprised that someone who has always been open about her membership of the Free Church of Scotland might hold true to its teaching even when a big job came along.

Even if they hadn’t known Forbes personally very well before they backed her, surely they understood the religious landscape of their country. The ‘Wee Frees’, as they are referred to in Scotland, are known to hold socially conservative views on marriage, abortion and other moral issues. Being shocked that Forbes also holds these views is like being shocked that a Catholic might agree with the Pope.

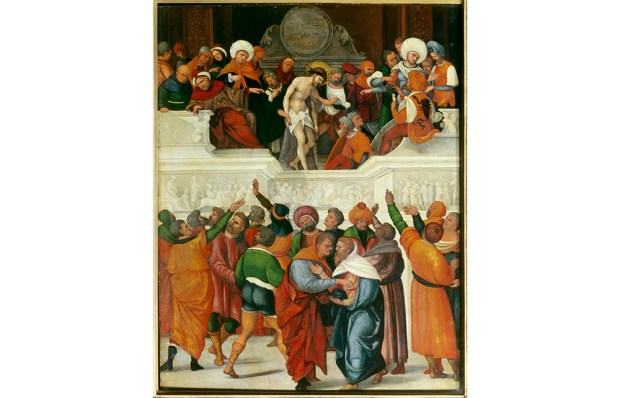

The ferocity of the reaction to Forbes is the latest example of the way a secular inquisition works against leading politicians with religious beliefs they actually stick to. When Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron quit his post after the 2017 general election, he said that it had felt ‘impossible’ for him to ‘hold faithfully to the Bible’s teaching’. He had spent much of his tenure dodging questions on gay sex, whereas Forbes has made the decision to confront them early and take the heat. But what the SNP leadership contest shows us is that the inquisition has changed a lot in the intervening six years – and in some ways for the better.

The slightly ludicrous surprise of Forbes’s supporters at her views on marriage was nothing compared with the shock on the faces of Nicola Sturgeon and other more liberal politicians who recently found themselves being grilled about their beliefs for the first time. One of the factors in the First Minister’s resignation was the mess over her support for gender self-ID and her Gender Recognition Reform Bill. Like Farron, she struggled to answer the same question over and over again; for her it was ‘Is the convicted rapist Isla Bryson a man or a woman?’ Her answers became less and less credible. During First Minister’s Questions, she ended up inventing a third sex of ‘rapist’ in order to avoid answering the question, saying: ‘What I think is relevant in this case or not is not whether the individual is a man or claims to be a woman or is trans. What is relevant is that the individual is a rapist.’ When she was asked whether there were ‘contexts where a trans woman is not a woman’ and whether that meant they were not equal to biological women, Sturgeon looked totally exasperated to have her thinking pulled apart.

Sturgeon will have grown used to those sorts of questions – which seek to suggest someone is falling prey to magical thinking – being asked of people like Forbes. The people with beliefs. Sturgeon and many in her party – and across politics, in fact – have ended up thinking that if you do not have religious views, then you are effectively neutral. Their worldview, they believe, is the default way of thinking and therefore the only people who have to explain themselves are the ones who deviate because of religion. Forbes’s answers on why she would have voted against gay marriage might not please everyone, but she has clearly had to think them through and practise arguing them to highly critical audiences. Sturgeon, on the other hand, was not used to being treated with such suspicion, even in the hurly-burly climate of Scottish politics.

Forbes and Farron are both evangelical Christians, but differ in their approach to politics. Forbes comes from a tradition that believes that lawmakers who allow, for instance, gay marriage are harming the very people they are supposed to be guiding and protecting by allowing them something that God sees is wrong. Farron, meanwhile, thinks it is wrong to legislate to force people to live as Christians when they are not.

I know a little of the world both of these politicians move in. For ten years I was very active in the evangelical church in England. I left the church seven years ago and hold no candle for its stance on many things, but even at the time I found it strange that my fellow believers would argue so passionately that they deserved freedom to practise their religion while campaigning vociferously against freedom for others to marry whom they chose. It seemed to me that if we wanted to be left alone to believe what we did about sin and salvation, we should afford the same to everyone else.

My own worldview has changed a great deal more since then, but I find it strange that these days no one accuses me of woolly thinking on moral issues, even when I haven’t interrogated my beliefs very much at all. I remain as capable of being daft and ignorant as when I had a faith, but now I’m not held to be suspicious.

Everyone has a worldview which needs interrogating. It’s no bad thing when politicians are asked – as Kate Forbes was – ‘what’s your position on the morality of the issue?’. It’s just that religious people in politics – and more so conservative Christians than, say, conservative Muslims – are much more used to others being suspicious of their beliefs and assumptions than secular progressives. Anyone who has had a faith will be used to being accused of believing in a ‘sky ghost’, or of having their beliefs about, say, transubstantiation mocked as magical thinking. Now, progressives hear the same insult thrown back at them when they defend gender self-ID: aren’t you guilty of magical thinking too by saying a man can decide he is a woman, regardless of chromosomes or genitalia? Many find that very question deeply offensive, and refuse to put the legwork into explaining themselves in a way they would demand of their religious peers. Of course, the main opponents of gender self-ID tend not to have much to do with organised religion either, but it’s easier to lump them in with the God-botherers than to give them a hearing.

This laziness is one of the very reasons the gender debate has ended up being such a mess. When you assume there is a default ‘right’ view, you stop interrogating its underlying assumptions. You stop understanding how to argue your case – or even when to change your mind. You ignore those who disagree with you and fail to spot when they have a valid critique of what you are trying to achieve. How much easier (and more cowardly) it is to simply declare that someone who thinks differently to you has no place in a modern political party.

Politics becomes flabby and policies dangerous when consensus crushes opposing arguments. Forbes clearly knew she had to answer for her beliefs – the worry is that her opponents don’t seem to think they deserve the same treatment.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in