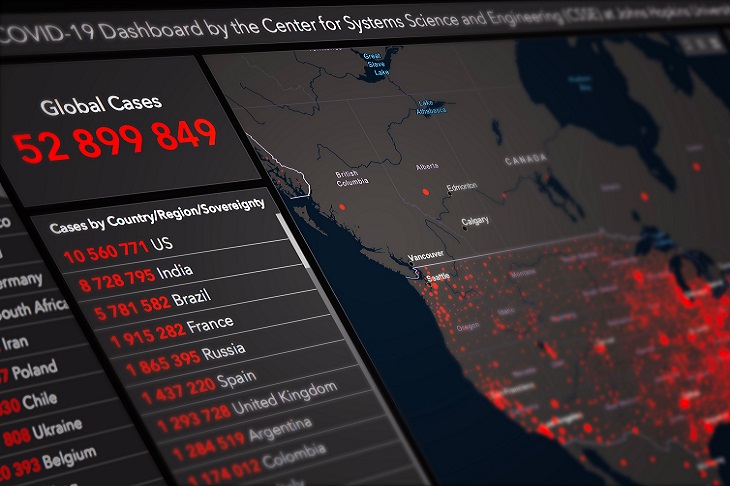

Many in the media, politics, and the health industry have expressed the view that Australia has fared well since the beginning of the Covid pandemic – but how true is the narrative?

There has been an emphasis on the benefit of achieving low Covid fatality figures, but what if the benefit of meeting the ‘dying with Covid’ metric is outweighed by the cost? A cost that includes excess mortality, debt, long-term health concerns, and many other variables that need to be taken into consideration.

The purpose of this article is to examine excess mortality across different regions to better understand what worked...

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in