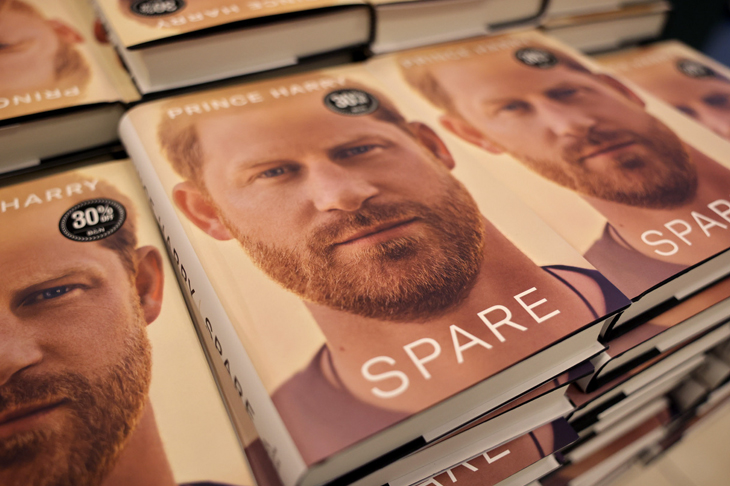

The Merriam-Webster dictionary people tell me that one of the most looked-up words on their website recently has been ‘archnemesis’ – because of its use by Prince Harry in his book Spare. He refers to his brother Prince William as ‘his ‘beloved brother and archnemesis’. The word ‘arch-nemesis’ (with the hyphen in the middle) is first recorded in 1901. Its origin begins with the word ‘nemesis’ which is much older (recorded in English from at least 1542) as the name of the ancient Greek goddess of retribution or vengeance, who reverses excessive good fortune, checks presumption, and punishes wrongdoing. From this source it has been applied metaphorically to mean any person who avenges, punishes, or brings about someone’s downfall, an agent of retribution. Agatha Christie called one of her Miss Marple novels Nemesis because Miss Marple was commissioned to track down a murderer from years earlier and bring them to justice. It’s an odd word for Harry to apply to Will since a ‘nemesis’ will only target a wrongdoer and seek to avenge wrongdoing. So, without realising it Harry is implying that he is in the wrong and Will is in the right. Clearly, he doesn’t mean that. He probably wants to imply that Will is his ‘archrival’. The ‘arch-’ prefix comes from an ancient Greek root meaning ‘chief’. It’s a prefix we see most often in words such as archbishop, but it has been more widely applied in recent years to create arch-enemy and arch-rival, while Sherlock Holmes’ adversary Professor Moriarty was an ‘arch-villain’. And if you are unlucky enough to have a number of people hunting you down to seek revenge the plural form of the word is ‘archnemeses’.

Recently Craig Pett wrote on this page about the Australian phenomenon of the ‘bogan’ and the whole world of ‘boganism’. So, perhaps it’s time to have another go finding the source of the word. We all know what a ‘bogan’ is (at least, in Australia – this is a distinctively Australian word): ‘an uncultured and unsophisticated person; a boorish and uncouth person’. In other words, a ‘bogan’ is a ‘westie’ (or a ‘bevan’, or ‘booner’, or ‘chigga’ – depending on which Australian city you’re in). Some people were surprised when I said (on Credlin on Sky News) that linguists have still not tracked down the origin of ‘bogan’ – basically, we don’t know where it came from. There is a lot of confidence that it has nothing to do with the Bogan River in western New South Wales (or any other place name), but that is the only certainty. Great Australian lexicographer Bruce Moore (who edited the second edition of the Australian National Dictionary) published an article in 2019 tracking ‘bogan’ back to Melbourne in 1984. In that year it appeared in a humour piece published in a student magazine from Xavier College. So, for a while it looked like ‘bogan’ was born in Melbourne. But Mark Gwynn of the Australian National Dictionary tells me that more recently a reference to ‘bogan’ has been found in Western Australia a year earlier – in 1983. So, at the moment WA is favourite as the place that gave birth to ‘bogan’. More than that we still don’t know. How was the word formed? What was the source? One of my correspondents suggested it might come from Henry Lawson who wrote about ‘Bogan Bill’ and ‘One-eyed Bogan’. But Lawson died in 1922, so how could his writings spawn a new word in 1983? Gwynn had an ingenious thought – the works of Lawson were dramatised by the ABC in a series called Lawson’s Mates in 1980. Is it possible the word was coined by someone who saw the series? That might be the case. The director of the Australian National Dictionary Centre Amanda Laugesen is updating the entry on ‘bogan’ and may be able to reveal more in the future. We await developments.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Contact Kel at ozwords.com.au

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in