Why did China end its zero Covid policy so abruptly? This question has confounded China-watchers and even the Chinese people over the last month.

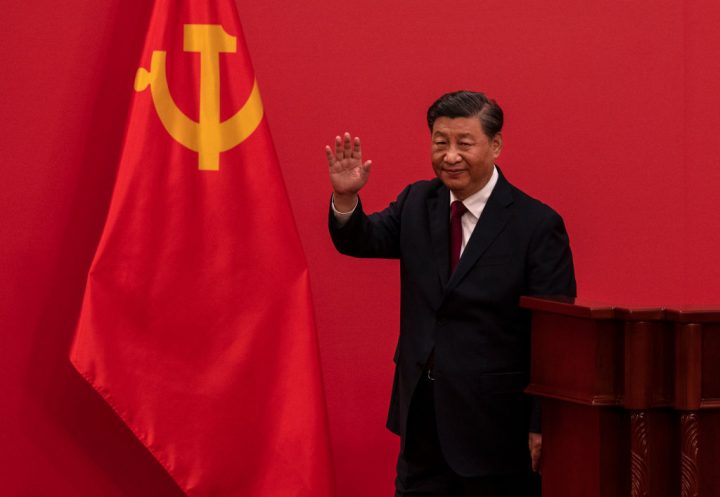

For the last three years, the Chinese government dictated its people’s lives to an extent unseen since the Cultural Revolution. Zero Covid had become part of Xi Jinping’s political legacy. It was touted as proof of socialism’s concern for human life, compared to capitalist indifference. And yet, almost inexplicably, zero Covid ended pretty much overnight at the beginning of December.

For the first time ever, the Chinese government appears to have admitted the real reason – zero Covid was failing to control the Omicron variant. In October, ‘new domestic cases kept appearing, signs of rapid transmission became ever more prominent, involving 31 provinces, regions and cities, with some regions seeing new infections for around three months, and the social cost of pandemic control climbed’, wrote the Xinhua News Agency on Sunday.

This and other revelations are part of a new timeline from the state media outlet, setting out the official narrative on the end of zero Covid. But even in this sanitised story, the state’s impotence against Omicron is clear if you read between the lines.

Even the heavy hand of the Chinese Communist party could no longer keep the virus at bay

According to Xinhua, discussions on opening China up (or in the language of the Chinese Communist party: ‘optimising pandemic control’) happened as early as November, before mass protests shook the country. ‘On 10 November, 2022, when Beijing was in the depths of autumn, an extraordinary meeting began in Zhongnanhai’, Xinhua says, pulling back the curtain on meetings within the secretive compound where China’s top leaders work and live. ‘It was at this meeting that the party’s central leadership made an important decision. For the first time suggesting twenty optimisation measures, sending out the signal domestically and internationally that China is proactively optimising its pandemic measures in a timely and appropriate way.’ In other words, starting to open up.

By that point, it was becoming increasingly clear that zero Covid was failing to control Omicron. Each day seemed to bring a new record number of daily cases (at least since spring’s Shanghai wave). By 10 November, over 800,000 people were in centralised quarantine facilities while millions more were under some kind of lockdown restriction. Chinese experts estimated that the R rate for Omicron was a steep 21. Xinhua writes lightly that ‘zero Covid was highly difficult [to maintain] and the social costs of pandemic control rose’. In other words, even the heavy hand of the Chinese Communist party could no longer keep the virus at bay.

The so-called ‘twenty optimisations’ landed a day later on 11 November, including measures such as shortening quarantine from ten to eight days. But the ‘signalling’ wasn’t nearly as clear as the central leadership hoped. Some parents were so afraid of Omicron that they pulled their children out of school in cities that did open up. Meanwhile, many local governments were apprehensive, fearing that they’d be scapegoated if the central government changed its mind again. The northeastern city of Shijiazhuang opened up the furthest, only to lock down again after nine days when cases continued to rise. Nobody knew if zero Covid was ending after all.

Then came the protests. The Chinese Communist party has never explicitly acknowledged them, but echoing the words of President Xi in his new year address, Xinhua writes: ‘In a country of 1.4 billion people, different people will have different demands. They’ll also have different views on the same issue’, and later, ‘at the end of November 2022, some members of the public raised awareness of problems with some regions’ lockdown measures and of over-bureaucracy and other pandemic control tactics, which caused high level concern’.

According to Xinhua, China’s Covid tsar Sun Chunlan met experts and representatives of frontline occupations on 30 November, at the tail end of the protests. They concluded that ‘China’s pandemic control faces a new situation, and a new mission’. A week later, zero Covid was effectively ended.

So it seems that, between the virus and lockdown fatigue, the CCP simply gave up. Infections were rising to an extent that were even pushing the limits of what an authoritarian regime with China’s resources could do. And though the CCP is clearly keen to underplay any impact the November protests may have had, the timeline suggests that these protests spurred the end of zero Covid, even if it was a path that the government was already going down. This is as much an admission of failure that we will get from Beijing, which is to say, not much of one at all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in