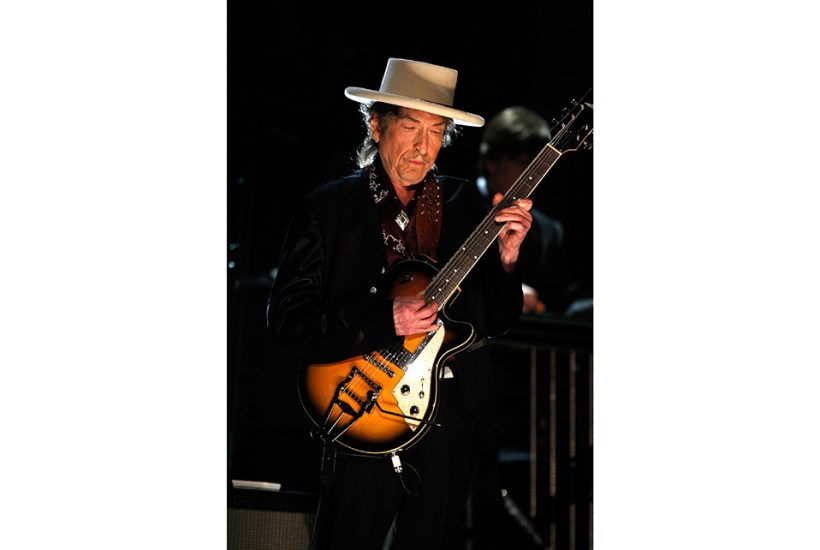

Between 2007-9, Bob Dylan compiled no fewer than 100 Theme Time Radio Hour broadcasts of songs he rated, prefaced by seemingly off-the-cuff verbal riffs on their meaning, history and importance. He was no natural DJ, but his love for the form shone through, as did a well-honed gruff ol’ man persona. The series was produced by Dylan’s ‘fishing buddy’ Eddie Gorodetsky, a successful sitcom scriptwriter (Mom, Big Bang Theory), with many of the selected songs more reflective of his taste than Dylan’s.

Now we have Dylan’s The Philosophy of Modern Song, and the suspicion remains (confirmed by a generous dedication) that Gorodetsky is in the wings, throwing out suggestions again. For Dylan’s idea of modern song is nothing of the sort. Rather, the vast majority of the 66 songs he hangs his rain-unravelled rants on come from a time when

we all shared a baseline cultural vocabulary. People who wanted to see the Beatles on a variety show had to watch flamenco dances, baggy pants comics, ventriloquists and maybe a scene from Shakespeare.

It was a period, he suggests, that began shortly after the second world war and presumably ended with punk, a movement which evidently passed him (and most Americans) by.

Dylan includes just two songs from the punk era (the Clash’s ‘London Calling’ and Elvis Costello’s ‘Pump It Up’), both British, and each a long way short of their best work. In the former’s case, he suggests, ‘this is probably the Clash at their best and their most relevant, their most desperate’ – a remark so wide of the mark it might have come from that doyen of off-centre rock criticism Greil Marcus.

Which brings us to the central problem with this book: the choice of songs. Even the godawful Grateful Dead have written better ones than ‘Truckin’ ’, some of which Dylan has performed. The equally redundant ‘Witchy Woman’ is held up to the light – hardly indicative of the Eagles’s brief moment in the sun.

Having allowed himself these few songs to crack the philosopher’s stone (without an introduction offering an over-arching explanation of what exactly he is trying to achieve), Dylan gives Bobby Darin and Johnny Cash two each, and has this to say about Bing Crosby’s lamentable ‘Whiffenpoof Song’:

[It] belongs to everybody, the fraternal order, the political machine, the silent majority and the wealth of nations. It’s predetermined, ordained, and comes right out of the book of Fate.

One longs to read lines such as the one he gave Nat Hentoff in 1966, describing traditional song as ‘the only true valid death you can feel today’. But there are no traditional songs put under the microscope here – not even ‘Jesse James’, his piece mentioning neither the song nor his chosen recording, from 1928. As the publisher’s press release suggests, ‘ostensibly about music, these essays are really meditations and reflections on the human condition’. Trade Descriptions Act, anyone?

Actually, such discursive departures from Dylan’s self-proclaimed brief are the coruscating core of the book: the best written, the most heartfelt and the most illuminating sections. Unlike his bestselling ‘memoir’ Chronicles (2004), a work of fiction, at times Dylan pulls back the covers to show his real self. Vietnam – a subject almost entirely absent from his recorded work – he describes tellingly as ‘a small war, fuelled by hubris and murky to the citizenry who were left unsure what they were fighting for’.

This time, when he gets upfront and personal, it is only the names that have been changed. A persuasive essay on Ricky Nelson’s ‘Poor Little Fool’ ends with him talking about Nelson being booed for playing new songs at a show in Madison Square Garden in October 1971. Remind you of anyone? But at no point does he reveal he was there, or that his presence is alluded to, twice, in Nelson’s fine riposte ‘Garden Party’.

The best chapter in the book, a six-page tribute to Johnny Paycheck, has the autobiographical resonance largely absent from Chronicles:

Donald Eugene [Johnny Paycheck] knew he was born for more than his birth name had in store. And by the time he was a teenager, his hometown could barely contain him… Johnny seemed to know from birth that he was on the run and his one hope to dodge the hellhounds on his trail even for a moment was by signing in under a different name.

In this instance, Donald equals Dylan.

Likewise, his man of the mountain persona is perfectly suited to some withering assessments of modern life:

That’s the problem with a lot of things these days. Everything is too full now; we are spoon-fed everything. All songs are about one thing and one thing specifically, there is no shading, no nuance, no mystery… And it’s not just songs – movies, television shows, even clothing and food, everything is niche marketed.

It’s hard to disagree.

Yet the book is surprisingly free of the apocalyptic edge Dylan gave the mini- sermons he preached to audiences in his gospel era (1979-80). He laments that ‘religion used to be in the water we drank, the air we breathed. Songs of praise were as spine-tingling as, and in truth the basis of, songs of carnality’. But he does so while philosophising on Harold Melvin’s execrable ‘If You Don’t Know Me By Now’. God knows why.

It all makes this biographer wonder where is the editor, and where is the consistent internal voice, the voice of a critic and philosopher. He’s here for sure, but even a man with a silver spade needs to dig deep.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in