Is unemployment beginning to bite? Or are the workless trying to rejoin the economy? That’s the key question after the unemployment rate rose to 3.7 per cent today.

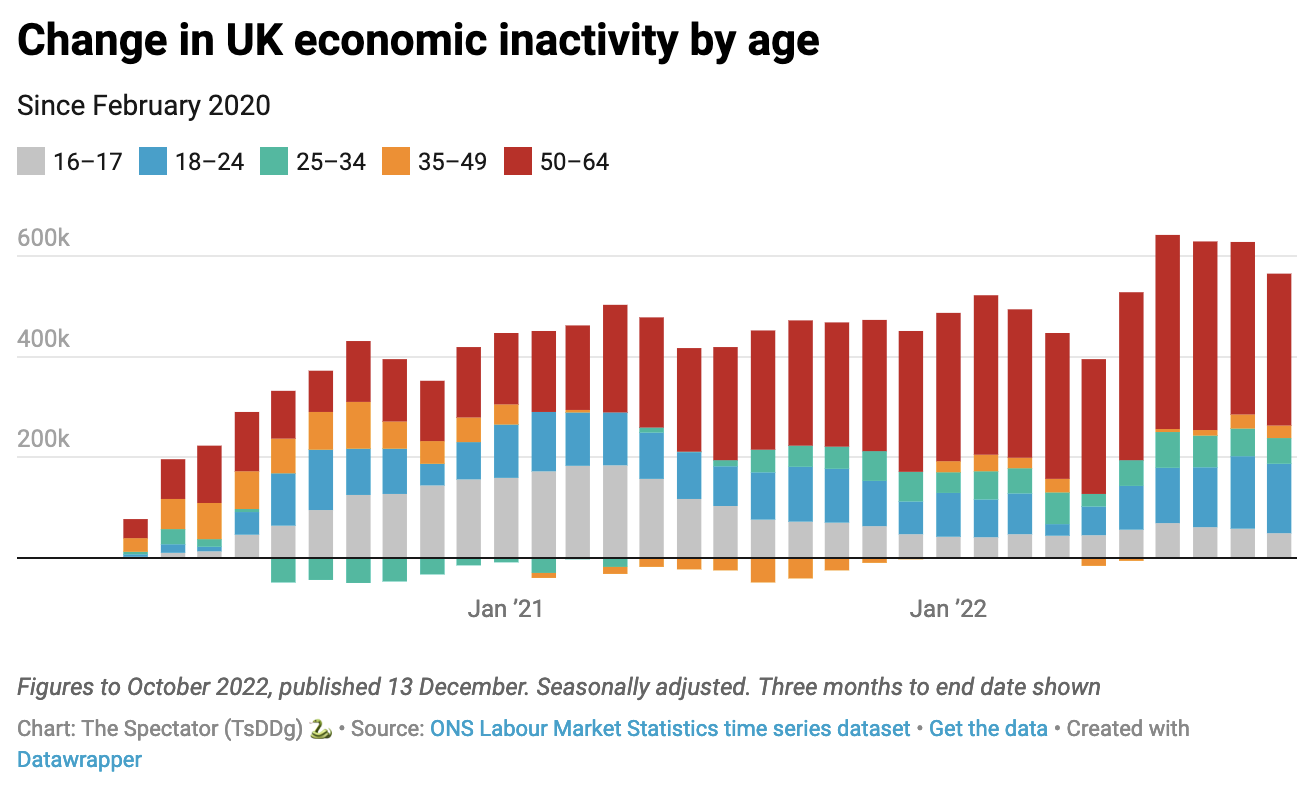

Figures released by the Office for National Statistics this morning reveal that even though unemployment is up, ‘economic inactivity’ is starting to fall, having previously grown by some 565,000 people since the pandemic and lockdowns. A city of workers the size of Manchester had stopped working and weren’t looking for jobs either, meaning they weren’t counted in the official unemployment figures. But this trend away from work might be beginning to reverse.

The number of people who are economically inactive has now fallen by some 76,000 compared with the previous three-month period. As a result both the employment and unemployment rates rose (by 0.2 and 0.1 percentage points). The unemployed are not moving into work, and workers are not losing their jobs either – instead previously inactive people are now saying they want to find work.

Long-term sickness had been responsible for the rise in economic inactivity since the pandemic, with a near record 2.5 million people out of the workforce due to ill health. What today’s figures reveal is that the reduction in inactivity is now being driven by older workers who may have packed in their careers early and those aged 50-64, who accounted for 65 per cent of the latest fall in inactivity.

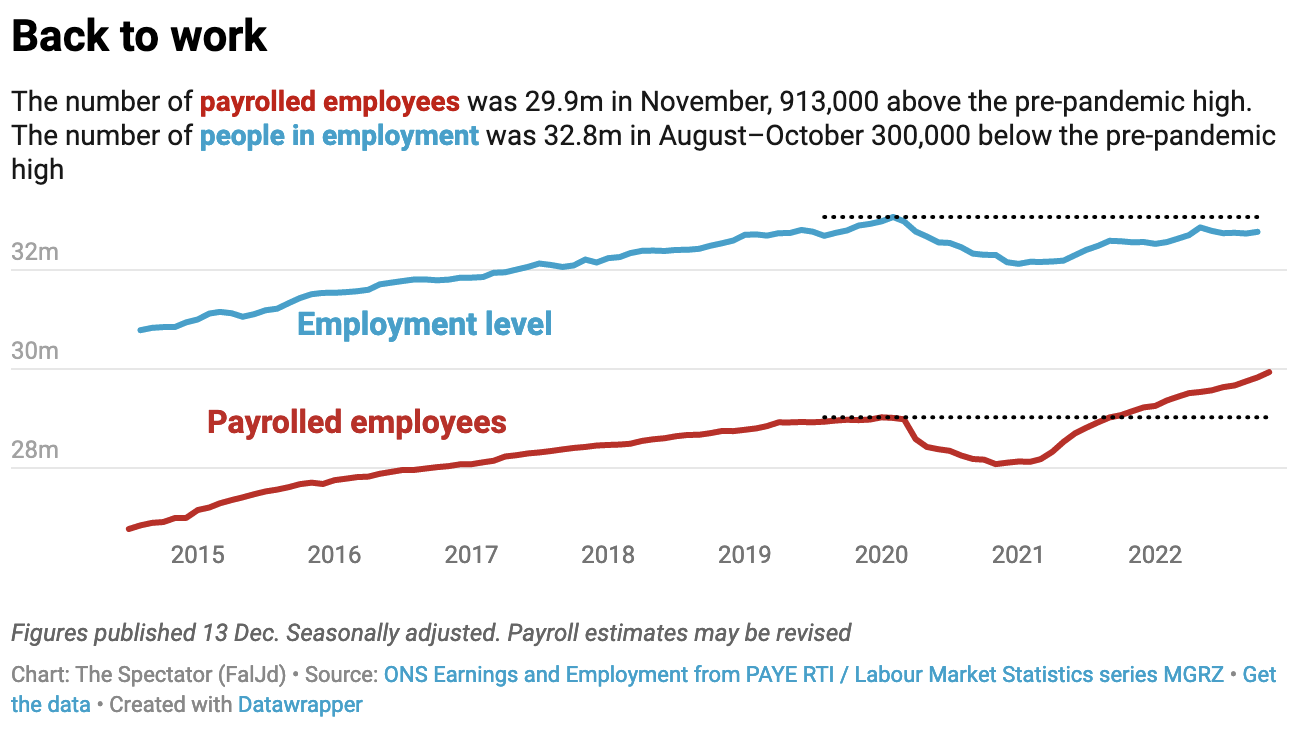

For the first time in months the government may have something to cheer about in the labour market figures, as more people look to return to the workforce. However, there are still some 300,000 fewer people in work than before the pandemic. The number of employees on payroll has continued to climb though and now stands at a record 29.9 million – some 913,000 higher than before the pandemic – possibly reflecting a move away from self-employed work.

Meanwhile the heat is slowly coming out of the labour market. Vacancies fell again to below 1.2 million having previously peaked at 1.3 million jobs in May. The fall is small but is the sixth monthly decline in a row. Earnings increased 6.1 per cent year-on-year, though this is still well below inflation which stood at 11.1 per cent in October. As a result, workers are experiencing at least a 2.7 per cent pay cut. There were 417,000 working days lost because of labour disputes in October – the highest level in over a decade.

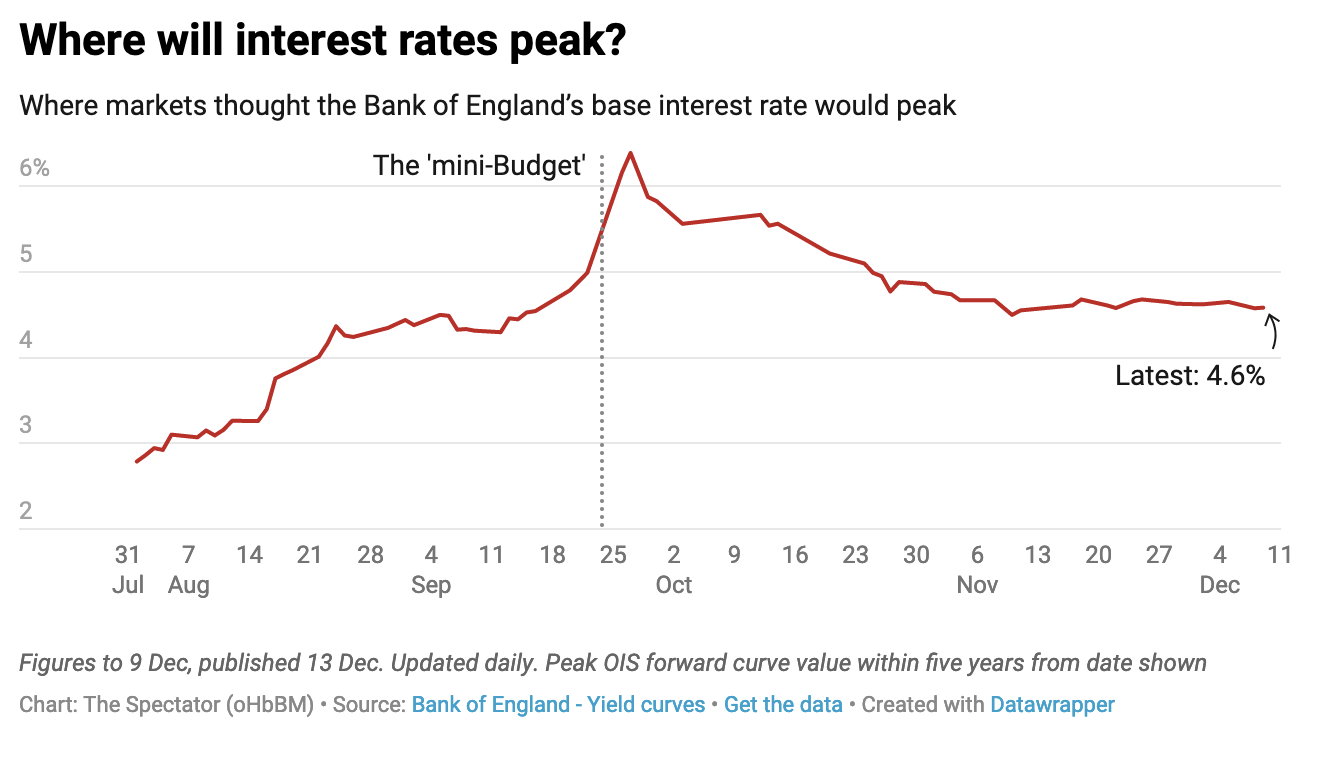

Markets are calmer than they were in the aftermath of the Kwartening ‘growth budget’ and the fall in economic inactivity will placate them further. But there’s still a long way to go. Traders still expect interest rates to peak at over 4.5 per cent, while the consensus remains that the Bank of England will raise the headline rate by at least 50 basis points at their meeting later this week. Though, given stronger than expected monthly GDP growth (0.5 per cent) yesterday and the gradual loosening of the jobs market today, a 75 basis points rise is not off the cards.

The lack of people willing to work since Covid and lockdowns goes a long way in explaining the economic problems Britain has found itself in. So the tentative good news, that more people are returning to the workforce, will please the government and employers. But whether this is a seasonal blip – or a sign things have peaked – remains to be seen.

The post Why the rising unemployment rate might not be such bad news appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in