Children’s writing has been having a bit of a moment over the past couple of weeks, after a conversation on social media between children’s authors gathered into a sort of cri de coeur about the public neglect of their craft. Children’s books, they said, are barely covered in newspaper review pages or on the radio these days. Prizes for their creators have dwindled in number – the Smarties and Guardian prizes have long gone by the board, and the children’s category at the Costa book awards went down with that ship. We all know about the dwindling stock of public libraries. The writers complained, too, that publishers are using celebrity name recognition for the path of least resistance: diverting their marketing budgets into ghostwritten pap by TV stars.

That, they rightly said, is a sad thing. Their complaints made some headlines, bounced the odd newspaper books page into promising greater coverage and even earned airtime on the Today programme. Good. Children’s writing is important: more important than adult literature, because it comes first. To adapt Jesus’s line that ‘nobody comes to the Father but through me’, we can say that nobody comes to Marilynne Robinson but through Winnie-the-Pooh. Everybody’s experience of reading grows out of children’s literature. It’s in nursery rhymes, fairy stories, picture books and comics that we learn the grammar of storytelling and that we first enter fictive worlds in which we can start to imagine ourselves as someone else. It’s from Dr Seuss (or ‘Doctor Zoiss’, as my perverse old friend Lord Hannan insists on pronouncing him) rather than Shakespeare that we first learn how words can bounce and pop against one another.

When a children’s writer gets taken up by his or her audience, they sell in a way that grown-up authors can only envy.

As it happens, we’re going through a bit of a golden age for children’s writing. Looking just across the bookshelves of my own children I see works by Katherine Rundell, Piers Torday, S. F. Said, Jeff Kinney, Malorie Blackman, Philip Pullman, Philip Reeve and Michelle Paver that are as accomplished in their fields – or more so – than the grown-up books we routinely see nominated for literary prizes. I think Julia Donaldson probably has the best ear for prosody since Auden. And for dark comedy give me Jon Klassen over O. Henry any day.

So I can see how frustrated writers like these, and those less established, get at the money and marketing oomph that goes into supermarket children’s books by, as Torday put it, ‘celebrities from other fields who have previously shown no interest in creative writing and see the children’s book market as a fairly pain-free way to extend their brand’. This is a bit tough on the likes of Charlie Higson, incidentally, a fine writer for children who happens to have had a telly career first; but for most it holds true.

I’ll admit it. My conscience twanged, a little, at talk of the barely-there coverage of children’s writing in the mainstream media. My instinct as this magazine’s literary editor, like my predecessor’s, has been to confine our coverage of children’s books to pre-Christmas round-ups. That’s not a rigid policy; it’s more a tendency. We carry reviews of literary-historical books about children’s writing and children’s writers, we notice the big ones, and we’ve recorded podcasts about children’s writing – Torday has been a guest, as has Philip Pullman. But there, nevertheless, it is. The reasoning is that most of our readers are adults, and that with our limited space we should concentrate on serving their interests as readers and thinkers rather than as buyers of books for their children or grandchildren.

Also, slightly, it’s a matter of cowardice. In the first place, we’d be sipping from a firehose. In the second, it’s peculiarly hard to write well – still less, usefully or authoritatively – about children’s writing as an adult critic. The things that make decently housetrained critics of literary fiction clap like performing seals – originality of expression, subtlety of characterisation, thematic complexity, oniony layers of irony and all that jazz – aren’t always all that important (or important at all) in children’s writing. Most kids couldn’t give a fig about a well-crafted metaphor, unless it’s funny. Critics of literary fiction get sniffy about heroes and villains, or the idea that it’s important to be able to identify with a character to enjoy a story, but that’s a lot of the game in children’s literature. And to elevate originality as a criterion for praise in children’s fiction is to be looking for the wrong thing altogether.

Children’s literature remains much closer to fairytale – which is to say closer to folktale, which is to say closer to myth – than the effete stuff we serve to grown-ups. And the essence of myth is old wine in new bottles. The Harry Potter books are among the most successful children’s books in history, and they are pic-n-mix compendia of styles and motifs from the whole previous history of children’s writing. I do not say that to deprecate the books or their creator: it’s exactly why they’re so great.

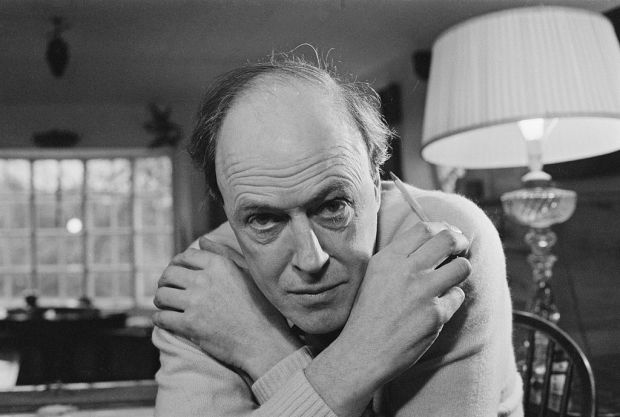

Roald Dahl’s work over the years has been deplored by adult critics for its crudity, its sadism and its vulgar humour – and it hasn’t made the faintest difference to how much children love it. Dahl had it about right, or about half-right, when he said: ‘Up to now, a whole lot of grown-ups have written reviews, but none of them have really known what they are talking about because a grown-up talking about a children’s book is like a man talking about a woman’s hat.’

I say half-right because it seems to me there’s a further wrinkle of complexity in the whole question: it’s not just the critics, but the authors themselves, who are (in Dahl’s quaintly sexist formulation) men talking about women’s hats. Children’s books are written by adults (often, historically, rather damaged adults) writing from or to their inner child. The children’s books of each generation reflect adult anxieties and ideas about children and childhood. It can be a matter of superb intuition or dumb luck when one or more of these mad hatters turns out to be a Philip Treacy.

That makes the history of children’s writing – where we can look at what did find an audience and how it was imitated and developed – a wonderfully fertile area of academic study. Bring on your social historians, your Freudians, your structural narratologists: come one, come all! But, boy oh boy, the new stuff is a moving target. It makes reviewing the latest Don DeLillo a walk in the park by comparison (and that’s before you think about attempting to assess the relationship between words and pictures in so many of them).

Do adult reviews of children’s books sell those books? In the sense that they influence buyers at book chains: I guess so. But publicity is a benign side-effect of literary journalism rather than the point of it. And book reviews are a conversation between adults. The conversations about kids’ books that really matter are between children. Word-of-mouth is important in selling adult books. It’s next to everything, I suspect, in selling children’s books. When a children’s writer gets taken up by his or her audience, they sell in a way that grown-up authors can only envy.

And yet, and yet. Maybe it’s better to have something about hats; even if it’s only grown-ups talking to each-other and we don’t know much about hats. What do you think?

The post What adults don’t get about children’s books appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in